Hankus Netsky: Activist Ethnographer

- Written by:

- John Marchese

- Published:

- Spring 2015

- Part of issue number:

- 71

Hankus Netsky has an expansive view of what’s important in the transmission of culture from generation to generation.

A dinner menu from a Catskills resort where a once-popular klezmer musician worked? To Netsky, that’s important evidence. A recording of an old man singing songs he learned as a kid in a small Carpathian Mountain village? Same thing. Netsky also believes there are cultural riches to be found in a woman’s letters, essays, and poems found in an tattic suitcase by her children years after her death.

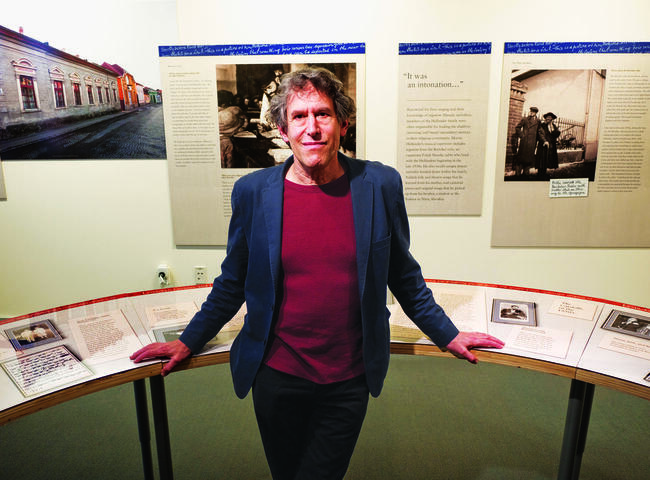

Those items are key components in the Yiddish Book Center’s Lee & Alfred Hutt Discovery Gallery, which Netsky curated. By incorporating the old-world memories of the late Morris Hollender (a Holocaust survivor and lay cantor who immigrated to Massachusetts in the 1960s), the mementos of Brooklyn clarinetist and bandleader Marty Levitt, and the contents of a suitcase belonging to Sonia Victor, a native of Vilna who wrote poetry and raised a family in the United States, Netsky offers a look at what he calls “the cultural legacy that resides inside one person.”

Netsky’s own story began in Philadelphia in the 1950s. His mother’s side of the family were musicians; his father owned a rag-trade wholesale business. Though Yiddish wasn’t spoken in the home, Netsky heard the language as a kid from the survivors who worked at his father’s shop and from a Hasidic rabbi his father befriended. Netsky started playing music early because in his family, he says, “that’s what you did.” When he got his first saxophone at the age of seven, his mother bought him a book of songs from the Yiddish theater. “You should learn these,” she told him. Though he studied jazz and classical music, he remembers, “in the back of my mind there was something Jewish that had to express itself in music.”

Netsky is a voluble man who seems perpetually amused. Often, as he tells a story, his sentences build like cresting waves that crescendo to the crash of a punch line and recede in ripples of laughter. But when he recounts a seminal moment in his life—attending a summer camp performance of a revue called Brecht on Brecht as a high schooler—Netsky becomes serious, even emotional.

“The last line of the play,” he remembers, “was ‘I feel like a person who carries a brick around to show the world what his house was like.’” When the play ended, Netsky was overwhelmed by emotion. Showing the world what the house was once like became Netsky’s mission. “That was going to be it,” he says, “for the rest of my life.”

By the mid ’70s, Netsky had finished a master’s degree at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. After attending a traditional Irish music gathering called a ceilidh, he was inspired to put together informal music parties where musicians could play Jewish music. Within a year, a group of more than a dozen serious klezmer players had coalesced into what would be called The Klezmer Conservatory Band. Their first gig was in February of 1980, and to Netsky’s surprise, “people were hanging from the rafters.”

Around the same time, Aaron Lansky was establishing the Yiddish Book Center in a factory loft outside of Northampton, Massachusetts. Both men have vague memories of how they first met. Netsky thinks his band played a party at the Center; Lansky jokes, “I don’t remember how I met him, but I’ve always known him.”

“Aaron and I had exactly the same impetus,” Netsky says. “It was a realization: ‘You mean they’ve been hiding all the good stuff?’” Both men felt a certain dissatisfaction with the way Jewish culture was taught in postwar America, with its focus on religion, Israel, and the Holocaust. It was what came before that interested them, what Netsky calls “this secret culture that seemed a lot more interesting than the one they were trying to spoon-feed us.”

The Klezmer Conservatory Band went on to great success, making records, performing all over the world, and earning recognition as a pioneer group in the revival and reanimation of klezmer music. It introduced many young people to Jewish music and helped revive the careers of older musicians from whom Netsky was eager to learn.

“I couldn’t get a book that told me anything about this music. There was nothing in English.” Voices of a People: The Story of Yiddish Folksong, by Ruth Rubin, who became a mentor to Netsky, “was pretty much it,” he says.

Netsky eventually found a way to learn more about the music. “I had to do interviews,” he says. “I had to be able to get information from people because nothing else was there. I decided to go back to school and learn how to do this. So I went back to school at age forty-one to get a PhD in ethnomusicology.”

As a doctoral student working on a dissertation, “I could say to the people I was interviewing, ‘This is going to be in a book. This is going to be preserved. This is going to be disseminated.’” (Indeed, a book based on Netsky’s research, Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia, was published in 2015 by Temple University Press.)

Soon after he finished his doctoral studies, Netsky was hired by the Yiddish Book Center to be its vice president for education. “It was a transitional moment for us,” Lansky remembers. “Up until that point the Center had focused most of its energies on rescuing books. It was like triage, because the literature physically was in danger of extinction. But collecting had finally calmed down and there were fewer emergencies. We were free to take an obvious next step—open up the treasures we’d found and share them with the world.

“There was no shortage of academics we could have chosen to be our first education director, but there was something different about Hankus. He had a heartfelt passion. It was the meaning of his life to discover and reclaim this culture.”

One of Netsky’s first priorities was to establish an oral history project. “Within two or three days of starting work I was going around with my Marantz cassette recorder looking for people to interview. This was a precious heritage that we had been denied. Within these walls—the visitors, the docents—were incredible resources that we needed to tap. I was very happy that the Center empowered me to do that.” That early work led to the creation of the Center’s Wexler Oral History Project.

Though he no longer works at the Center, Netsky can often be found there, including onstage at its annual Yidstock: The Festival of New Yiddish Music. In 2013 he was named by the Forward to its list of that year’s fifty most influential American Jews. He has served as musical director for a series of Jewish music projects with violinist Itzhak Perlman; one became a PBS Great Performances show and another, In the Fiddler’s House, recently sold out Carnegie Hall in a benefit performance for the National Yiddish Theatre-Folksbiene.

During a visit to the Center’s Lee & Alfred Hutt Discovery Gallery this spring, Netsky mentions those gigs but quickly returns to the time he spent with Morris Hollender. Netsky plays a snippet of Hollender singing a melody for Psalm 118 on an iPad in the gallery, singing along for a while.

“This melody was taught at the Nitra yeshiva in Slovakia,” he says. “That was destroyed by the Nazis. Morris knew it, along with hundreds of other melodies that I collected over time. These people are sources of things that would disappear if they didn’t share it. It’s really great music. These are great melodies. They’re not written down anywhere. It’s not just something in a book. You get to hear him sing it. The important thing is to associate it with a person and a personality and a feeling.

“I can be that person who’s telling people about this now that he’s gone,” Netsky says. Carrying the brick around to show people.