Beyond Time: The Paintings of Samuel Bak

- Written by:

- Elizabeth Pols

- Published:

- Spring 2010 / 5771

- Part of issue number:

- 61

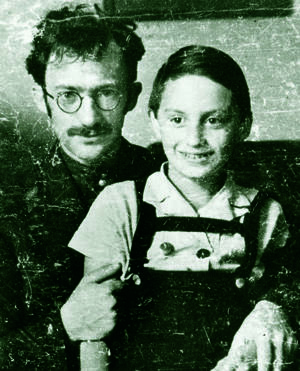

The battered snapshot is vintage 1940s. An intense young man with wild hair and spectacles stares straight at us. On his knee sits a young boy wearing overalls and a shy, sweet smile. They are the poet Avrom Sutzkever and the painter Samuel Bak.

More than a half-century after the photographer captured that moment, Sutzkever would write, “The painter Samuel Bak is baked into my heart. – Iz mir der moler Shmuel Bak azoy ayngebakn in hartsn.…” The phrase goes beyond sentiment or affection or even the kind of admiration a poet might have for a painter. To understand the relationship, you have to go back in time and in place, to Vilna, to the ghetto, to 1942, when nine-year-old Samuel Bak first met the great Yiddish poets Sutzkever and Szmerke Kaczerginski. There, a connection of such intensity between artists not only made sense, it was essential to survival. From the moment of their meeting, Sutzkever claimed the painter as “my ghetto brother.”

He and Kaczerginski recognized Bak as a child prodigy, mentored him, and organized his first public exhibition – in that ghetto.

The three were among the few to survive the Nazis’ destruction of their city, and their lives would continue to intersect for decades to come. Just after liberation, as he and his mother were fleeing Vilna for Lodz, Poland – taking only what they could carry – the boy Bak entrusted many of his paintings and drawings to the safekeeping of the two poets. When Bak and Sutzkever both resettled in Tel Aviv in 1948, their friendship was renewed and grew. Sutzkever wrote about Bak’s painting and translated and published an early autobiography of Bak’s in his magazine Di goldene keyt. He also addressed several poems to Bak’s mother. In “Gehernter Moyshe,” he asked,”Where did your son find the clay to do this Moses?” The woman – Bak’s mother – answered, “In the graves of the Jews.”

That Sutzkever, 96, should have died only days before Pakn Treger met with Bak in his Massachusetts studio made for a bittersweet segue into our conversation. Bak recalled that Sutzkever, in 1948, had donated a number of his friend’s preserved early paintings to the New York YIVO. The painter remembered that Sutzkever “once gave me as a gift … a manuscript of all the poems that he wrote under the German occupation in the ghetto.… He had such a beautiful handwriting.” Bak, in turn, donated the manuscript to YIVO in 2005, on the occasion of receiving the organization’s Vilna Award for Distinguished Achievement.

Perhaps the most poignant exchange, though, occurred much earlier, in 1942, when Sutzkever and Kaczerginski gave Bak the Vilna Pinkas, the town’s 19th-century record book. While they hoped that Bak might survive and preserve for the future this tangible chronicle of their city’s history, their immediate motive was to supply the budding artist with drawing paper: the old Pinkas still had many blank and usable pages. Over the next year Bak filled the book with such vigorous drawings as the Moses (right). When the Nazis liquidated the ghetto in September of 1943, Bak hid the Pinkas under his coat as he and his mother were loaded onto a truck for the HKP labor camp. The Pinkas was his constant companion until the following March, when the children’s aktion forced the hasty and daring escape, engineered by his father, of Bak and his mother. During the escape the boy was hidden in a sack and lowered from a window. The Pinkas and his father were left behind.

Painted in Words, Samuel Bak’s memoir, tells what became of that boy, his family, and the Pinkas. In his foreword to the book, Israeli writer Amos Oz calls Bak one of the great painters of the twentieth century. Painted in Words, he says, “is unique. Despite being suffused with a sense of loss, horror, degradation, and death, it is ultimately a sanguine, funny book, full of the love of life, rocking with an almost cathartic joy.”

Published in 2001, the memoir charts Bak’s peripatetic life from his 1933 birth, through the war in Vilna, and throughout the next 50 years. Uprooted, painting incessantly, living on three continents, Bak returned to Vilna, finally, in 2001 for a long-anticipated emotional visit. “I am a perfect wandering Jew, who always carries with him his roots, travels always with books that break his back, and has all those languages [he speaks seven], and none of them perfectly well. Impossible!” says Bak from his comfortable home near Boston, where he and his wife, Josée, have spent the last 16 years – the longest either of them has been in one place.

He began life as the adored only child of ambitious parents who recognized and nurtured his artistic talent from his earliest childhood. Bak’s photographic memory enables him to evoke those idyllic prewar years with cinematic clarity – just as he does the horrors that came after. His extended family and friends – especially his grandparents – are finely and lovingly depicted in Painted in Words, so much so that when they are killed in the woods of Ponary their loss became personal to this reader, 70 years after the fact.

“This is what made me who I am. This is why I never really think, ‘What am I going to paint now?’” says Bak about his life and the way it informs his work. “My idea is to let out this thing – which is the self – that wells up in me. Because I had those parents, I had those grandparents, I had that war.…This is one of the reasons why I thought that it was very important to write this book because it gives, I think, the best key to what I am trying to paint.”

Bak characterizes his painting as “speaking about the unspeakable,” and he identifies the late 1960s as the moment when he found his voice. The evolution of that voice involved an educational as well as an emotional odyssey. In post-liberation Vilna, Bak’s mother located the perfect first teacher for her son: the academician Professor Serafinovicz, who cultivated the boy’s natural draftsmanship by having him draw from the broken plaster casts she herself had dug from the ruins of the city’s Academy of Fine Arts. In Lodz he studied with an impressionist; in Munich, a constructivist; in Jerusalem, an expressionist; and in Paris, a “post-neo-classical cubist.” Bak catalogs these teachers with affection and respect but still describes himself as self-taught.

“When I started painting with one artist, and the second, and the third, and the fourth, each one was telling me a very different story. So, it kind of cemented in me the sense that there is not such a thing as an absolute idea which is right.” Bak soaked up most of his knowledge about art in museums rather than classrooms. To go “from a Picasso to a Piero della Francesca and from there to a Bonnard and bring out all these connections which exist between them: this was my real learning."

He spent 1956 to 1966 in Paris and Rome where “there was an incredible freedom, you could do practically anything. But not tell stories in paintings, and not do anything which might be considered theatrical.” He did very well in that world of abstract art, establishing a name for himself and selling his work. In 1966, by then married and a father, Bak moved his growing family back to Tel Aviv.

He also began to move his work in a radically new direction. Unexpectedly, a curator from the museum in Vilna (now Vilnius) contacted Bak with the news that the Pinkas had survived and might be available for him to borrow for retrospective shows. Those hopes were soon dashed by the start of the Six Day War and the consequent break in diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and Israel. But the thought of the Pinkas’s survival unleashed a flood of memories just as time and distance from the Shoah were giving Bak the courage to face his past. That courage, together with his consummate technical skills and rebellious nature, compelled Bak to break with the reigning art establishment and make paintings that were not only narratives, but took as their subject the trauma of his dramatic survival.

“When you have a taboo in art it’s always interesting to break it. So I chose a kind of painting that creates an illusion of a space, which is like scenery for the story I expect the one who looks at the painting to write from the clues that I am giving. The stories can evolve in many different directions. So, it’s like life.”

To speak about the unspeakable, to tell those stories without making people shudder and turn away, Bak turned to the pictorial language of realism – both that of the Great Masters and of the surrealists – “because it helps me to hide much better what the paintings want to reveal.… I make the unspeakable look as if it happened in the 18th century. Or beyond time.”

And maybe beyond place. In Stone Age (1968), a painting within a painting, we are poised between cataclysmic events. The ruined house and its torn trompe l’oeil canvas are testaments to recent devastation. It, and we, are set in a beautiful but claustrophobic landscape where at any moment the boulder-like clouds might crush us, might raze our improbably balanced little home. What is this unstable world, where a stony sky mirrors a stony ground; are we in a strange asteroid belt? In this ambiguous and threatening landscape we have no guide but the questioning artist, whose presence is implied by the inner canvas.

In To the Memory of R. K. (1968) Bak marks the dead center of the composition with a bullet hole, one of three that shatter the colossal stone egg cup occupying the fore-ground of another exquisitely rendered but hostile landscape. Something awful has happened. There’s a more subtle, hallucinogenic air to In the Park: in the foreground of a gorgeously realized and glowing landscape (think Giorgione, think Titian) sits the stillest of still-lifes: a white teapot, a bowl and spoon, an empty eggshell, and cup. They are all of marble, all ancient, all enormous, all cracked. Has a powerful quake shattered a bizarre domestic monument? Is that really stone? And is that teapot really so monumental or has the painter toyed with our sense of scale by thrusting it so far into the foreground?

Such questions typically have been answered with labels: for the last 40 years the words “Samuel Bak” and “surrealism” appear often in the same sentence. Even as Pakn Treger goes to press, a March 15 issue of Newsweek features an article by Cynthia Ozick about the authenticity of Holocaust-related art in which she lauds “Bak’s astounding visionary surrealism.”

But Bak makes a distinction between surrealism and what he does, which is to use the devices of surrealism. “It’s not a very precise thing, and I don’t mind if people call my work surrealist. All I can say is that surrealism usually deals much more with the subconscious; while I am dealing with things that come to the level of my consciousness. I’m using symbols and metaphors that represent a reality which is a little shifted….”

Painted in Words tells us, in fact, that the battered crockery and unyielding spoon are more literal than imagined. In the Vilna ghetto, the young Bak was taken to meet an important artist, someone Sutzkever thought could be the right tutor for him. But the artist had just been arrested, leaving behind in his room only his unfinished drawing “in black and white, composed on two or more sheets of paper. The surface was held together by thumb-tacks.… Only the perfectly immaculate white cup comfortably centered on its saucer and the erect handle of the spoon radiated something of a serene assurance, as if they were the ghostly signs of an impossible dream. With all my being I tried to absorb this mesmerizing image.”

That powerful image, which Bak first painted over 40 years ago and appears today in works like Where It Ends II (from the “Return to Vilna” series) is just one example of Bak’s slightly shifted realities. Most of Bak’s important images – angels with broken wings; monolithic chess sets; clocks without hands; jerry-rigged mechanical birds; colossal keys; Hebrew letters and the Tablets of the Law; people who are part human, part prosthetic, part sculpture (echoes of the salvaged plaster casts of Professor Serafinovicz); the architectural stacks of books; strange and lovely pears – are rooted in his life’s experiences. In his paintings they are brought to the level of icons, both real and symbolic.

Art itself is a principal element in Bak’s work. Incarnations of the unfinished drawing by that vanished ghetto artist still inhabit his paintings. Countless trompe l’oeil canvases offer fully realized paintings within paintings, confounding our distinctions between the real and the visionary. Sometimes the paintings are finished but battered and eloquent, and sometimes they are as yet unpainted, invoking an absent or mute artist, or an artist from the future.

What is the role of the artist: recorder of events, interpreter of events, manipulator of events? “All of that,” Bak says. “When you do the kind of painting that I do, it must get away from that one meaning. Can this thing have two meanings, three meanings? Then it’s okay. Then it can be used. But if it is something that only means one thing, then I better keep it away.” The self-referential canvases within his paintings also reflect his sense of humor, which leans toward the ironic. “Irony is the most important tool in art; in literature, certainly; in story-telling, certainly. Where would Kafka be without irony? Irony is this possibility of taking a distance from things. And you need a distance to put the thing into a context.”

Bak likes also the challenge of taking a stereotype and transforming it into a mythology. “What could be more banal than a woman who sleeps with another man? But when it becomes Anna Karenina, you don’t say this story doesn’t interest me. Or a poor student who kills an old lady for money? Crime and Punishment. All this mythology is always on of the border of banality. It’s kind of tricky….”

The proof that Bak is the master of such tricky territory is the paintings he bases on appropriations of familiar works like Michelangelo’s The Creation of Man. In Creation of War Time II (from the series “In a Different Light”), Bak boldly appropriates from both Michelangelo and the 20th-century surrealist Rene Magritte. He takes the charged gesture between the hand of God and the hand of man – the one we recognize not only from the Sistine Chapel but from refrigerator magnets and silly birthday cards – and uses it to question the power, nature, and very existence of God. Here, Bak represents God as the negative space in a blasted brick wall (an allusion to Magritte’s transparent bird) but the reference to Michelangelo is unmistakable even in simple silhouette. Only God’s pointing hand occupies positive space, as a plaque secured to the brick wall by a nail. Adam mimics the Michelangelo pose, but he has an inmate’s shaved head and wears prison garb and an expression of exhaustion and futility. He reclines, inexplicably, on a purple cloth – the perfect discordant note – in the rubble of a collapsed house, unexploded bombs, and a blank canvas. No brave new world, this. When, in Adam with his own Image, Bak substitutes an upside-down canvas of Adam’s own hand for the figure of God, he surely begs the question: Is God merely an invention of needy man?

Another series based on an appropriated image is “Icon of Loss,” in which Bak works with the notorious Nazi photograph known as the “Warsaw Boy.” It’s a departure for Bak, and in it he takes an enormous risk. Though the Holocaust has long been his subject, his use of specific imagery has been discreet. Now, prompted by distress that a powerful iconic image has been reduced to a cliché, Bak openly adopts the Warsaw Boy – a boy who might have been Bak himself in “the same cap, same outgrown coat, same short pants” or his murdered best friend Samek. In a challenging and inventive series of some 75 paintings, Bak restores the authenticity of the original image while reaching new levels of meaning. Like Michelangelo’s Adam or Dürer’s angel, Bak’s Warsaw Boy is instantly recognizable, whether he appears as a suggestive patched shape in a distressed brick wall, as vandalized statuary, as the side of a mountain, or as a flesh-and-blood child who confronts us with hands still bleeding from a crucifixion. Many times the boy takes the form of a flat scrap-wood construction, which like a macabre scarecrow or primitive effigy intensifies his vulnerability and dignity. When Bak masses these constructions to fill the entire picture plane, as in Collective I and II, they have the power of a demonstrating and accusatory mob. Bak says he sometimes feels he would like to paint “one million of these Warsaw boys, for the number of children who were murdered”; but the cumulative effect of these 75 paintings brings him closer than the actual number suggests.

When asked about the sources of his prolific output, Bak blames his own curiosity. He typically begins to explore one idea, which invariably leads to another idea, “because every painting is like a Russian Babushka. You open it and there’s another Babushka inside.… I have now in my studio about three or four different series. One I am working on is Adam and Eve… I’m thinking continuously about that story.… God, if he was intelligent (and I’m not sure he is), created them in order to break the Law. Once you start to think about that, then Adam and Eve in paradise don’t interest me – what becomes interesting is that Adam and Eve survived the Holocaust…. they have lost paradise and become Everyman, Everywoman. It becomes a subject which is very encompassing. So you cannot solve it with one painting or two paintings. I mean, I can paint Adam and Eve for the rest of my life!… At a certain point you have to finish with them.”

Bak rises early every day and paints “as if it was the last day.” He exhibits at a marathon pace, commemorating his 75th year in 2008 with a show of the 75 “Icon of Loss” paintings at the Pucker Gallery, on Newbury Street in Boston. This spring, “Figuring Figures,” a show of Bak’s newest work which deals with the subject of displaced persons opens at Pucker. At any given time he may work on as many as 120 paintings at once. He acknowledges his huge production with an understated “I keep very busy,” but notes “it’s only ten percent of what is in my head!” While there is real urgency, even compulsion, in his need to paint, in his need to tell the stories that he does, he maintains there’s nothing “more joyous than the hours that I spend in the studio. Had I the possibility to paint 48 hours of every 24, I would do it.”

In this, you hear an echo of his young self. Woven through the deprivations and losses of Bak’s war years are accounts of rescues and acts of kindness that provide a telling detail: where most of us would remember rescuers for their gifts of food or a warm bed, Bak’s life-and-death comforts are paper and pencils. A sign painter in the labor camp recognized the boy genius and offered him cardboard and paper: “How did you know I needed them?” Bak asked. “I saw the way you looked at them.” Sister Maria, a nun who hid Bak and his mother in the months after their escape from the labor camp, is remembered by Bak as someone who “supplied me with paper, colored pencils, and old and worn children’s books.…I drew and drew and drew.”

Today Sam Bak’s studio is well stocked, serene, and orderly, with pleasant light bathing the clean white walls and the honey-colored wood floors. A nearly finished painting from the Adam and Eve series rests on the big easel in the center of the room, while a few others from the series, slightly less developed, wait propped against a nearby table. His paints are within easy reach on an industrial wheeled cart and brush-filled buckets line the top of a bookcase filled with CDs (Bak listens to audio books as he works). In a handy side room dozens of works-in-progress are stacked neatly according to size and shape, and elsewhere are pristine canvases ready to receive the paintings “queuing up” in his mind.

Conspicuously absent, though, is the sprawl of open reference books, source photos, and rough sketches that clutter the studios of most figurative painters. The drawings that appear to be studies for finished paintings were actually composed after the fact, in what he calls the “portrait of a painting that I painted” – a more concise version of the expanded idea. Bak does any sketching for a painting directly on the canvas, in the form of under-painting that is then covered over by the finished work.

Also missing are props for still lifes, models, or careful arrangements of drapery – all of which are staples of Bak’s compositions. They, too, are in his mind. “These are somehow things that pass from your brain into your fingers.” That direct path from his mind’s eye to the canvas is critical to his process: “What I am interested in is to get the image as powerfully as it is in my capacity,” says Bak. “The idea is an abstract thing: it has the speed of thought, which is still faster than the speed of light, I think.” He dedicates 99 percent of his time to the actual execution of the painting, a process that owes much to his photographic memory and extraordinary draftsmanship, but also to his sensitivity to the resonant rhythms and patterns of the world. Bak is a man who notices and absorbs things deeply and offers them back, transformed.

Much of his work’s transformative power has to do with its sheer beauty. The worlds he paints for us are full of chaos and questions, but in the calculated decision to make this difficult artistic journey, he invites us along. “I’m fishing in my art. I’m trying to aesthetically seduce people so that they will look into these things, because what I’m going to tell them is maybe not very pleasant. But I want still to speak because I’m very talkative!” Bak pushes each painting – he claims they all start as “messes”– until every detail contributes to the visual harmony that ultimately defines beauty. But form always follows function: the fierce intelligence of his work never succumbs to mere cleverness, and its beauty can be terrible. “The painting has its own needs and tells me what to do.… I very often try to make a certain dissonance by using too harsh colors, maybe a very harsh blue, saying ‘Look!’ so that this fairyland beauty is speaking of something very different.” He no longer needs to prove that he can paint as meticulously as the Dutch masters, so some of his more recent surfaces have more vigor and texture and a little less polish.

When Bak says, “Every work of art is always a kind of testimony against the artist,” he means that no painting of his is ever as good as he would like it to be. To this day, he feels he “could a little improve it here, could improve it there” and he doesn’t have the same feeling of sureness that he had all those years ago as a child prodigy drawing in the blank pages of the Pinkas.

The Pinkas has served as a kind of poignant punctuation in his life. After the tantalizing disappointment of 1967, the Pinkas resurfaced in 2000. Rimantas Stankevicius, a representative of the now-independent Lithuanian government, contacted Bak with the news that the Pinkas was being exhibited in the Jewish Museum in Vilnius “in a huge glass box, like a sacred object,” with enlargements of Bak’s drawings hanging on the surrounding walls. This was the beginning of a reconnection to his native city that led to a retrospective show in Vilna and his first hesitant visit to his birthplace in 2001.

The visit unleashed what even the prolific Bak calls “a frenzy” of painting, the fruit of which was the 2007 “Return to Vilna” show at Pucker Gallery. These paintings – more than 100 – poured out like automatic writing, as if transmitted by a higher power. A cortege of new imagery appears. There are the forsaken pillows and teddy bears of childhood. There are stacked books like those behind which Bak and his mother hid. There are strewn books suggesting a scattered culture. There are trees bearing books instead of fruit. And there are herds of airborne and rootless trees, as though a horrified nature had uprooted the complicit Ponary forest.

Finally, in what the writer Lawrence Langer refers to as Bak’s “battle to convert inner pain into a serene visual homage,” there are both somber memorials to each member of his lost family and the brighter tribute paintings he calls their mementos. Painting like a man possessed – “only that here you are possessed by your own self” – Bak produced a potent series that binds the long-ago child prodigy to the prodigious Samuel Bak of the present.