Cheder Years

- Written by:

- Shmarya Levin

- Translated by:

- Maurice Samuel

- Published:

- Fall 2013

- Part of issue number:

- 68

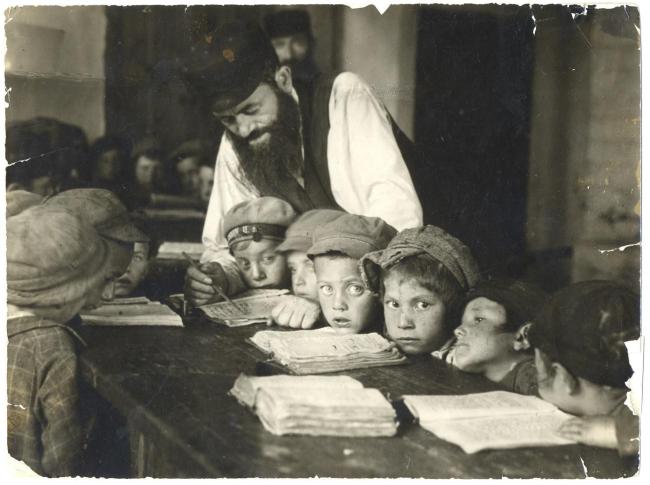

The days of my freedom, my unrestrained happiness, draw to a close. I remember clearly the evening which was the overture to the second act in the drama of my life. At the close of one Sabbath, when the farewell prayer to the holy day had already been intoned and we sat with friends round the samovar, my father drew me over to him and said, “My son, most children begin their cheder (traditional Jewish prinary school) at the age of five. I think yours is a better head than most, and we’ll start you a year earlier. From tomorrow on, you will be a cheder boy. Enough of this wild freedom. It is time for you to begin learning the Torah.”

Two things it’s never too late to do: to die and to become a teacher in a cheder. Only the Jew who has known the old life can understand the bitterness of that proverb, for to become a teacher in a cheder was the last resort of every failure. If a young husband who, according to the ancient custom, had been living with his in-laws while he studied the sacred book suddenly found himself compelled to learn a living; if a merchant met a disaster and was thrown onto the street; if a decent paterfamilias saw his house burn down and found himself without a roof over his head, the first thing he would turn to, till fortune changed, would be the job of the melamed, the teacher of the cheder. It was one of the most melancholy phenomena in our Jewish life of the last century, for it shows clearly how low the concept of child education had fallen among us. Parents sent their children to cheder in obedience to tradition, but they paid little attention to the accomplishments or the character of the melamed.

There were three kinds of teachers. The first taught the child simply to read Hebrew. The second taught the elements of the Five Books of Moses and the remainder of the Bible—for with us, the Pentateuch occupies a place of special sanctity: it is the first thing taught to the child, and it looms largest in our religious life. The third teacher taught Talmud. Children passed through the three grades of melamed (teachers) according to age. But it was very, very seldom that the melamed possessed anything like the necessary qualifications. The tender hopes of a coming generation fell into hands which were frequently ill-chosen and sometimes downright dangerous.

It was a happy Sunday morning in the early spring, soon after Passover. My body still had on it the taste of a new suit, with real pockets. That morning my mother woke me early, gave me a bit to eat—I was still considered young enough to eat before prayers—and sent me off with Father to the shuhl (synagogue). There I sat down right next to him—a privilege which I seldom enjoyed—and he bade me follow the prayer leader with the closest attention. Some of the responses I already knew by heart. When prayers were over, my father led me to Mottye the melamed, and there the formal introductions took place: “Mottye, this is your youngest pupil. Schmerel, this is your melamed.”

Immediately after melamed and pupil had been officially introduced, the entire company, relatives and friends, with Grandfather Solomon at the head, repaired to our house. There a fine table had been prepared, with sweetmeats and drinks. Iwas seated in the place of honor, and a toast was drunk. My mother herself served the guests. To me was handed a prayer book. Two of the pages had been smeared with honey, and I was told to lick the honey off. And when I bent my head to obey, a rain of copper and silver coins descended about me. They had been thrown down, so my grandfather told me, by the angels. For the angels, he said, already believed in me, knew that I would be a diligent pupil, and were therefore prepared to pay me something in advance. I was immensely pleased to hear that my credit with the angels was good, and I stole a look at my mother. A sweet, tender smile played on her lips, and I could not make out whether it was my credit with the angels that pleased her so or whether she was keeping back some happy secret of her own.

When the ceremony was over my father lifted me up, wrapped me from head to foot in a silken tallith, or praying shawl, and carried me in his arms all the way to the cheder. My mother could not come along—this was man’s business. Such was the custom among us. The child was carried in the arms of the father all the way to the cheder. It was as if some dark ideas stirred in their minds that this child was a sacrifice, delivered over the cheder—and a sacrifice must be carried all the way.

Mottye the melamed had his own house, standing on a little hill. The house seems to have been patterned after Mottye and not after his wife; it was small, dilapidated, and overgrown with moss; the moss was the counterpart of his sparse goat beard. The door was small, but Mottye went through without bending. My father had to stoop. Inside, he sat me down without further ceremony, gathered up the prayer shawl, and left the cheder. There I was, on a small, hard wooden bench with nine other children, two of them my first cousins—Gershon, the son of Uncle Meyer, and Areh, the song of Uncle Schmerel—both of them a year older but also beginners, like myself. There and then, without preliminaries, I was plunged into the work.

The table in front of the bench consisted of rough planks, and the heads of the big nails which fastened them together stuck out so that it was easy to get caught on them. The children sat on two benches, five on each side of the table, and Mottye the melamed sat at one end. He had taken off his topcoat and had replaced his hat with a pointed skullcap: thus his face lay between two points, the upper point of the skullcap and the lower point of his goat beard. In one hand he held a wooden pointer. He did not sit still but swayed back and forth as he taught. He bade us keep our hands above the table, look out for the nails, and sit respectfully.

The children had to be broken in, for it was impossible to drag them away abruptly from their play. So during the beginning we were in cheder for only half days; that is to say, from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon. But later, when the class was divided into groups, we would get only brief intervals of liberty during the day.

After the first term children were confined to the cheder for the entire day. The rebbe, who thus became the complete master of the child, did not, however, pay any attention to the question of physical cleanliness. When the mother complained that the child came home in the evening altogether too dirty for a single day’s play and study, the rebbe used to retort sarcastically that he was not a wet nurse. He thought it beneath his dignity to worry about such matters.

I cannot stress too often the dominating, the exclusive, role the cheder played in the life of the young Jewish boy. He saw his parents only for half an hour in the morning, before first prayers, and then for an hour in the evening, before he went to sleep. So it happened that in the majority of cases there was little intimacy between parents and children and even between brothers if they happened to be learning in different cheders. As between brother and sister, there was even less opportunity for the ripening of friendship and affection. A second factor raised a wall between brother and sister in their earliest years. Girls were not sent to cheder and had nothing to do with studies. The brother looked upon his sister as another kind of creature, belonging to another world. As if God had not created them different enough, the gulf between them was made still wider by differences in education and in duties. When my youngest brother grew old enough to differentiate between those grown-ups whom he might call by the familiar second person singular du and those whom he had to address formally in the plural Ihr, he placed in the second class even his older sisters, and it took us quite a time to make him understand that he was entitled to the same familiarity with them as with the other members of the family.

Excerpt from “Cheder Years” from Childhood in Exhile by Shmarya Levin, translated by Maurice Samuel. Copyright 1929 by Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

The full English translation is out of print, but can usually be found second-hand at minimal cost on Amazon and other sites.

The full, two-volume Yiddish text is available for free in our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library: Volume 1; Volume 2.