Everything Old Is New Again

- Written by:

- Julie Michaels

- Published:

- Summer 2013 | 5773

- Part of issue number:

- 67

“We see ourselves as the stewards of a profound and beautiful tradition, tasked with the challenge of keeping it fresh without getting too far from our soul.” —Niki Russ Federman, a fourth-generation owner of Russ & Daughters

To the wandering Jews of the Diaspora, food was a form of cultural baggage. It was the one thing they carried with them when forced to move for reasons of politics or persecution.

Food was also a blessing from God, made sacred by their prayers and regulated by strict dietary rules. Is it any wonder that, for a tribe with no permanent home, the dishes they set upon their tables helped define them as a people?

Add the memories of an immigrant culture, where Old World traditions helped anchor families in a new and unfamiliar continent, and you can easily explain the yearning for smoked meats or grandmother’s matzo ball soup. The deli became for the Jews what Paris cafés were to the French: a home away from home.

The wonder of the Jewish pantry is that it is filled with such variety. The Ashkenazim of Eastern Europe and the Russian Pale brought with them the kugels, bialys, and gefilte fish of their region. Since these were the Jews who colonized America’s cities, this is the food we most identify as Jewish. But there is an equally rich tradition of Sephardic cooking, carried by Jews who wandered to Spain, the Middle East, and Turkey. It contributes the subtle spices of Moroccan ta-gines as well as interpretations of Arab street food.

Today, a new generation of chefs, restaurateurs, and purveyors are keeping with—or building upon—Jewish culinary tradition. Some are reinterpreting their own childhood memories, often skipping their parents’ American shortcuts and returning to the cooking styles of their bubbies. Others are exploring the less familiar recipes of the Jewish Eastern Mediterranean. Whatever their inspiration, they are finding a through- line of culture that links the food they eat to the history of their people.

A visit to six New York restaurants, a bakery, and two appetizer shops shows us how these traditions are playing out in the ever-evolving story of Jewish food.

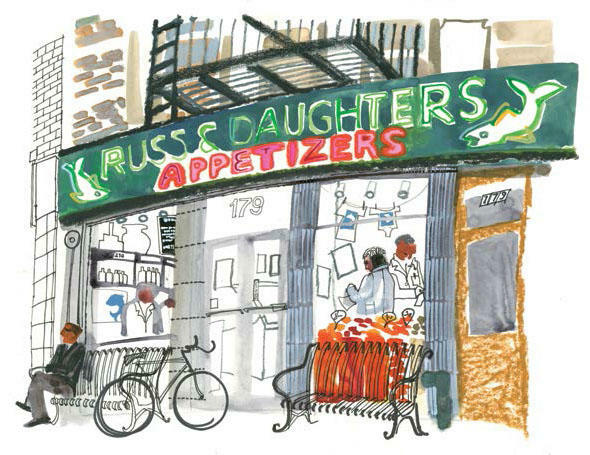

Russ & Daughters

179 East Houston Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan

Well before feminism was a concept, Joel Russ began selling herring from a pushcart on the Lower East Side. In 1914 he opened a shop, and in 1933 he renamed it Russ & Daughters to acknowledge his new partners in the family business. Today, Joel Russ’s great-grandchildren—Niki Russ Federman and Josh Russ Tupper—are the fourth generation to run the business, and both are committed to maintaining its traditions.

Dubbed “the Louvre of Lox,” Russ & Daughters offers a classic selection of smoked and cured salmon, herring, bialys and bagels, apricots, nuts, and cream cheese. In 2000 the Smithsonian designated Russ & Daughters “a part of New York’s cultural heritage.” And so it remains, though Joel Russ never got to sample the shop’s latest offering: chocolate-covered matzo with sea salt and caramel.

Kutsher’s Tribeca

186 Franklin Street, Manhattan

There is no better indicator of modern family life meeting Jewish food tradition than the Friday night take-out dinner offered by Kutsher’s Tribeca. It’s called Shabbox (or Shabbos in a Box) and offers the basics for any Jew who grew up with ties to the Borscht Belt: matzo ball soup, roast chicken or brisket, a bunch of sides, and a dessert of rugelach or mini black-and-white cookies. Whole-wheat challah is included, and for five bucks they’ll even throw in a pair of Shabbos candles.

By offering such nostalgic fare, along with home-cured pastrami, wild Alaska cod gefilte fish, and potato latkes “just like Mom’s,” owner Zach Kutsher is paying tribute to the Catskill resort founded by his grandparents more than 100 years ago. The New York Jews who spent their summers and weekends at Kutsher’s were mostly of East European descent, which meant Yiddish-flecked conversations, stand-up comics (think Alan King, Milton Berle), and what chef Tommy Higuchi-Crowell calls “white man’s soul food.” Nobody was on a diet.

Even as Kutsher’s Bistro reinforces this past, they acknowledge modern influences. For example, there’s a “borscht salad” of beets and goat cheese accompanied by fingerling potatoes and artichokes and a brisket sandwich served “southern style.” But mostly people come for the memories.

Mile End Deli

97A Hoyt Street, Brooklyn

If you think “artisanal Ashkenazic” cooking is an oxymoron, then you haven’t been watching the modern deli movement. Exhibit A is Brooklyn’s Mile End Deli, an homage to the Jewish quarter of Montreal, where owner Noah Bernamoff savored his first smoked meat sandwich.

Bernamoff took his yearning for good deli to Boerum Hill, where in 2010 he opened Mile End Deli in a tiny converted garage. His goal was to “redefine delicatessen classics by fusing the spirit and craftsmanship of the past with a thoroughly modern sensibility and aesthetic.” In other words, the bowtie noodles for the restaurant’s kasha varniskies are not store-bought but rather pinched by hand the way his Lithuanian great-grandmother might have made them. The deli also cures its own smoked meats and fish and makes its own pickles.

Mile End doesn’t strive to make deli new, just better, by introducing kreplach, shmaltz, and cholent to a whole new generation.