Simkhele Shoykhet

- Written by:

- Sarah Hamer-Jacklyn

- Translated by:

- Allison Posner

- Published:

- Fall 2013 / 5774

- Part of issue number:

- Translation 2013

Born to a Hasidic family in Noworadomsk, Poland, Sarah Hamer-Jacklyn (1905–1975) was a Yiddish writer and actress known for her vivid literary portrayals of Jewish life in the shtetls of Eastern Europe and of the immigrant experience in North America. Her experience in the theater was said to have brought a particular richness to her writing, noted for its thick descriptions, lively dialogue, and complex, captivating characters. Hamer-Jacklyn’s papers can be found in the archives at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, the city that she called home for most of her life.

An excerpt from Shtot un shtetl

My Aunt Hadassah was deeply disappointed. Three children she’d brought into the world, all three of them girls. Her husband, Shloyme Shoykhet, had only one wish: to leave the world a kaddish, a son to say the prayer for the dead for him after he was gone. When Hadassah got pregnant for the fourth time, she fasted, gave to the needy in the Holy Land, helped find matches for poor young brides, and begged the Master of the Universe to consider her charity and deem her worthy of bringing a son into the world.

When Hadassah was in the last months of her pregnancy, she dreamed she had a boy. When she told her mother-in-law about the dream, the old woman waved her hand dismissively. “Why do you believe such foolish dreams, Hadassah? You’re going to have a girl. You come from a family that has only girls, just like in our family we have only boys.”

The crestfallen young mother stared at her mother-in-law, realizing her foolishness, and hung her head.

Hadassah’s three daughters — Sorele, Chanale, and Tsipele — were two, four, and six, respectively. They all took after their father and their grandmother with their black hair, brown eyes, and dark skin. Hadassah was the exact opposite, with delicate white skin, large blue eyes, and blonde hair with a golden red sheen. When her head was shaved after the wedding, she cried over the loss of her golden locks. The golden red wig, or sheytel, she began wearing looked just like her own hair.

Her mother-in-law, Devoyre-Hindl, was always boasting about her lineage. She came from a line of rabbis, was in fact married to one, and had four healthy sons (three of whom were already married). When her husband passed away, she moved in with her youngest son, Shloyme. In Hadassah she had found a good match. Her daughter-in-law never did anything without first seeking Devoyre-Hindl’s opinion. She felt like a nobody next to her mother-in-law, who had brought four kaddishes into the world.

When it turned out that the fourth child was a boy, she wept in happiness. Devoyre-Hindl took one look at the newborn and grumbled, “Feh! A redhead.”

The bris was celebrated with as much rejoicing as a wedding. They named the child Simkhe-Meyerl, after his grandfather, a great rabbi.

The boy grew. His parents brimmed with pride. At nine months he was already walking. At a year he was speaking. At two he could recite parts of the prayers his father taught him. When he was three years old he could write his own name. People were saying the child was a genius.

Hadassah became pregnant again and was sure that this time it would be another boy. Simkhe-Meyerl’s arrival had increased her confidence, and she now dared to assert herself in the daily goings-on of the house; she wasn’t shy and raised her voice when her daughters were making too much noise.

The fifth child was born. It was a girl. Hadassah looked at her little daughter and wept silently. Her mother-in-law comforted her and told her to thank the Creator that at least she had been worthy of bringing one kaddish into the world. It had most likely been decided above that she would have no more sons.

With each day Simkhe-Meyerl became more spoiled. His mother was continually dazzled by him. He was the apple of his father’s eye. Wherever Shloyme Shoykhet went, his son went with him. To the house of study and to the slaughterhouse. He even brought the boy to religious assemblies.

When he was five years old, Simkhe-Meyerl started learning Torah commentary. His parents repeated over and over to their friends and relatives how their son was already a scholar.

The boy soaked up all of the praise and grew arrogant. He was constantly at war with his sisters. When one of the girls went to complain to their father or mother to report that he had snatched away her doll or poked her, their parents always sided with Simkhe-Meyerl. Only the grandmother would stand up for the girls.

Simkhe-Meyerl’s star began to wane with the arrival of the sixth child, his little brother, Tsadikl. As soon as the grandmother saw the infant’s black hair and dark skin, she clapped her hands together and cried out, “Tsu lebn un gezunt — to life and health! — he’s the spitting image of my husband, may he rest in peace.” She never left the child’s side. Meanwhile, she kept reminding his older brother that he wasn’t so special now that he was no longer the prince of the house.

Tsadikl was a happy-go-lucky child: he was mischievous, he laughed, he could already play patty-cake. Suddenly everyone’s attention was fixed on the little boy. Just as before, when everyone was so taken with Simkhe-Meyerl’s cleverness, now his parents and the rest of the household praised Tsadikl’s every move. Tsadikl’s shouting. Tsadikl’s standing up. Tsadikl’s shouting by the cupboard – he’s found a little jar of preserves and stuck his hand inside and he’s licking his fingers! Everyone laughs, everyone is so proud of Tsadikl. Whenever someone from the family comes to visit, Tsadikl is put on display.

Meanwhile, Simkhe-Meyerl wandered around the house feeling forlorn. He also wanted to show off. So he stuck his tongue out. When no one bothered to look at him, he stood on his head with his feet in the air. His grandmother let out a shriek — only a sheygets, a non-Jewish boy, would do something so ridiculous. That’s no way for a nice young man to act — and she predicted that nothing good would ever come of him.

Simkhe-Meyerl felt abandoned. He regarded Tsadikl as he would a bitter enemy who had invaded his kingdom and wanted the crown.

Simkhe-Meyerl’s sisters took their revenge on him after the arrival of their new brother, and day after day they became bolder. Silently, so no one would hear, they tormented the already miserable Simkhe-Meyerl.

It was between afternoon and evening prayers, and the sun was just about to set. A ribbon of light fell across a dozing Devoyre-Hindl. Tsadikl was asleep. From outside came the muffled shouts of children playing. Hadassah was quietly moving around the kitchen. All of the sudden a frightful scream came from the child’s cradle. Mother and grandmother dashed into the bedroom. Before them was a strange scene.

Simkhe-Meyerl was leaning over his little brother, clutching a knife. He was mumbling something quietly under his breath. With his little hand he was rolling up the child’s throat as a butcher does when he prepares to slaughter a chicken. Hadassah let out a terrified scream, threw back her head, and fainted.

Devoyre-Hindl was at the boy’s side in a single leap. She snatched the knife out of Simkhe-Meyerl’s hand, examined the baby’s neck, and saw that it was unharmed — the dull, milkhik knife still clean — and she let out a sigh of relief. The cold butter knife seemed barely to have grazed the child’s throat, from which Tsadikl had emitted the blood-curdling scream. When Hadassah came to, Tsadikl was already laughing, and Simkhe-Meyerl was crying from the slap his grandmother had given him.

After the incident, the house was turned upside down. All the knives were put under lock and key, and Tsadikl’s crib was moved next to his parents’ bed. Simkhe-Meyerl was forbidden to go anywhere near his brother. His grandmother trailed him everywhere, calling him the “red-haired murderer.” She told the story to all of their relatives and friends, and soon the whole town knew what had happened. No matter how much Hadassah begged her to keep quiet, she refused. The boy acquired the nickname “Simkhele Shoykhet” — Little Simkhe the Slaughterer.

Simkhele stopped eating. He went around in a daze, he withdrew from the world, he no longer answered when people spoke to him. If he ever set foot near the crib to take a peek at his brother, the house went mad. He did poorly in his studies and took out his anger on his sisters, who constantly teased him and called him “Simkhele Shoykhet.”

* * *

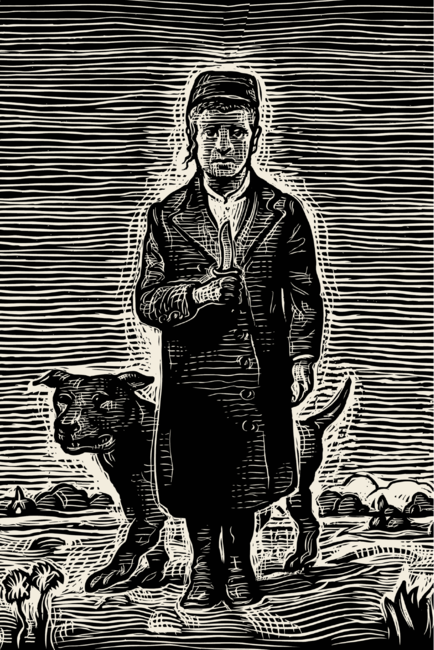

Every Shabbos, Vladek the “Shabbos goy” paid a visit to Shloyme Shoykhet’s house to perform all the tasks prohibited to Jews on the Sabbath. Each time he brought his son Stashik, who was around the same age as Simkhe-Meyerl. The peasant boy was fair-skinned with flaxen hair, and whatever the season he went around in a ragged jacket and long sleeves, the whole ensemble cinched with a cord. He was followed by his big black dog, Babchik. Oftentimes Vladek was drunk, and his son was left to take over as Shabbos goy.

No one really knew exactly when Simkhe-Meyerl befriended the sheygets, but it was certainly because of the dog. He often disappeared from the schoolroom and snuck out to the broad green meadows on the edge of the town, where Stashik would be waiting for him with the dog, and Simkhe-Meyerl, the perfect miniature of a traditional Jew, could be seen running next to Stashik, his skirts bouncing and side curls fluttering. The dog, Babchik, ran beside them. He tackled Simkhe-Meyerl joyfully, barking and licking his hands and face. The boy rewarded him with pieces of challah, chopped liver, and eggs from his pockets, which his mother had given him to take to school. He divided the portions equally between Babchik and Stashik. In return for the treats, the dog performed tricks the boys had taught him: he fetched a ball, he stood on his hind legs to catch a sweet that Simkhe-Meyerl threw him. From begging at the Jewish houses Stashik could speak a little Yiddish. So Simkhe-Meyerl spoke Yiddish to Babchik too, and he beamed with happiness when he saw how well the dog understood his language.

At some point people learned of these secret meetings, and once again Shloyme Shoykhet’s happy house was thrown into a tumult. Now everyone kept Simkhe-Meyerl away from Stashik and Babchik as well as from little Tsadikl. The older boy used to wander alone from room to room, staring through the windows at the shack across the way where his dear friends lived. To tame his loneliness and frustration, he used to paint people with the heads of wild animals and children with the faces of monkeys. He always added a tail.

The winter was a cold one. All the windows were covered with frost flowers. It was quiet in Shloyme Shoykhet’s house. Devoyre-Hindl was bustling about the oven. She opened the door and threw in some wood, which crackled festively as it caught fire. A lovely warmth spread through the room. A big kerosene lamp burned on the long table. At one end of the table sat the three girls with little scissors, absorbed in cutting out paper birds and dolls. At the other end of the table Hadassah was sewing a little white jacket for her youngest son. In the kitchen the housekeeper, Tsivye, was polishing the silver candlesticks. Her sad love song came through the open door:

The years they run,

The years they fly,

Love always reaches an end,

Even the best and most beautiful.

Now the time has come.

“Love, shmuv — tfu!” Devoyre-Hindl did not like the singing. “Quiet now, you’re going to wake the child.”

Simkhe-Meyerl was wandering forlornly about the house. Suddenly he came by the table and grabbed a paper doll. His grandmother shouted, “You sheygets, you! Why are you moping around with nothing to do? Go sit down and study.”

Simkhe-Meyerl didn’t answer. Out of the corner of his eye he was watching his sister, who had started to tease him quietly: “Simkheleh Shoykhet, you sheygets, why don’t you go play with your dog?”

Their mother told everyone to quiet down. Chanale put down her pair of scissors for a moment. In the blink of an eye, Simkhe-Meyerl grabbed the scissors and made a snip. He now clutched a red side curl in his hand. He looked sideways at his grandmother. Devoyreh-Hindl let out something between a squeal and a howl, and with fists clenched she lunged at the boy. At the same moment Hadassah jumped up from her chair. With her arms outspread like wings, she stood between her mother-in-law and her son and snapped, “Don’t hit him!”

She snatched the golden lock of hair from her child’s hand and cried wordlessly. An uproar ensued. Everyone was talking at once, but Devoyre-Hindl’s thundering voice could be heard above the din. “The boy’s become a hoodlum, a goy — vey, why have I been so cursed! How could this happen to the family? Maybe he’s been possessed by a dybbuk? Or a devil?

She turned to her weeping daughter-in-law and demanded, “Tell me the truth, have there been any dybbuks in your family, or even, God have mercy on us, a convert?”

Hadassah quickly stood up from her chair. Shloyme Shoykhet had meanwhile appeared in the doorway. Devoyre-Hindl was the first to run to him and blurt out what had happened. He stood as if paralyzed. He dropped unthinkingly into a chair and sat there like a statue. Everything his mother and his wife said to him was met with silence. He seemed somewhere very far away, as if he could hear nothing and see nothing. He had sunk into a deep melancholy. Had some spiteful soul, a ghost, God forbid, seized his son to tempt him to evil? He stood up abruptly and started pacing back and forth across the room like a soldier on his watch. It became deathly quiet in the house. No one dared make a sound. All of a sudden Shloyme Shoykhet halted and declared, “On Shabbos, I’m going to take him to see the Gerer Rebbe.”

Very early on Friday morning, Shloyme Shoykhet and his son set off to the Gerer Rebbe for a cure.

When they returned, an amulet hung from Simkhe-Meyerl’s neck that the rebbe had placed there himself. He had blessed the child and instructed him to be good and pious.

The boy seemed to have turned over a new leaf. He was obedient, quiet; his parents believed that the rebbe’s blessing had healed him. With a weight lifted from their hearts, they prepared for the wedding of Shloyme Shoykhet’s niece. The journey all the way to Zhemenits would be a long one, the first half by horse and wagon, the second by train.

Simkhe-Meyerl was certain he would get to go. He had already told all of his school friends he was taking the train to Zhemenits, and he had promised to bring them back caramels.

He could not have been more bitterly disappointed when he learned that Tsadikl would be taken along while he was to stay behind. His father told him he couldn’t miss school. When Simkhe-Meyerl started to cry and told his father he wanted to go too, Shloyme Shoykhet answered, “How can I take you to a wedding with one side curl? You’re an embarrassment. You want me to be the laughingstock of the town?”

So the boy stayed home.

The following Thursday, everyone prepared for the family’s return. The housekeeper cleaned the house and polished the pots; Chanale, Tsipele, and Sorele washed and put on their nice clothes and began guessing what wonderful things their mother and father would bring back for them from the wedding. Simkhe-Meyerl promised his sisters he would give them his present if they swore not to tell that he’d been playing with Stashik and the dog. When his sisters refused, he tried to bribe them with his prized pocketknife. He was even willing to hand over the amulet blessed by the rebbe. Tsivye agreed not to say anything, but his sisters wouldn’t keep quiet. They were set on telling their parents.

The night before Shloyme Shoykhet was to return with his wife, child, and mother, Simkhe-Meyerl went missing.

The next day, Tsivye and the rest of the family ran everywhere looking for him. No one answered at Vladek the Shabbos goy’s house.

Shloyme Shoykhet and his wife returned in the middle of the night. They were greeted by a house full of people. Simkhe-Meyerl’s sisters, who before had so mercilessly teased their brother, were red-eyed from crying. Devoyre-Hindl clapped her hands together and wailed, “Vey iz mir, something must have happened to Simkhe-Meyerl!”

As soon as Hadassah and her husband found out their son was missing, they too raced over to Vladek the Shabbos goy. They found him there half drunk. His wife was standing over a tub of wash, scrubbing calmly.

The panicked parents wanted to know if Vladek and his wife had seen their son. “Yes, yes, we saw him here — he and our boy ran off together. They took the dog with them.”

As Hadassah sobbed and wrung her hands, Vladek tried to comfort her. “Don’t cry, Pani Hodessa, my kid runs off all the time, but he comes back after a day, sometimes two… maybe three. They’ll come back.”

“He’s never coming back,” Shloyme Shoykhet said in a broken voice. He took out a red handkerchief and turned to the corner so his wife wouldn’t see him wipe away a tear.

Click here for the original story from Shtot un shtetl

Allison Posner is a graduate student in Comparative Literature at Indiana University. She is currently a Fellow at the Yiddish Book Center. *

*I have been unable to reach the copyright holder of Sarah Hamer-Jacklyn’s work. If anyone has information about the holder of these copyrights, please contact me at [email protected]