Voices from the Vault: Yiddish Writers Speak Again

- Written by:

- Nancy Sherman

- Published:

- Fall 2011 / 5772

- Part of issue number:

- 64

Few cities can feel colder than Montreal in deep winter, when columns of snow and ice-riven sidewalks discourage even the hardiest from venturing outside. But not very long ago, thousands of the city’s Yiddish-speaking citizens, many of them refugees and survivors from Eastern Europe, sought out human warmth and intellectual fire in the meeting rooms of the Jewish Public Library. Every week, from the 1950s through the 1980s, Yiddish writers from across North America, as well as from Israel and Europe, offered inspiration and solace to listeners whose journeys had been tumultuous and often tragic.

Officially founded in 1914, the Jewish Public Library (JPL) served in the post-war years as Montreal’s foremost Yiddish cultural center, sponsoring artists and activists of all ideologies. From its grassroots beginnings at the turn of the century in response to the needs of a small immigrant community, the library grew into a dynamic forum for Yiddish literature and culture, supplemented by a network of shules (secular Jewish schools), a daily Yiddish newspaper and a host of periodicals, and a popular Yiddish theater. Evenings at the JPL might feature poetry or prose readings followed by lectures of scholarly and educational significance. Montreal residents like Rokhl Korn, Melech Ravitch, Chava Rosenfarb, and Mordecai Richler regularly presented their work; Avrom Sutzkever traveled six thousand miles from Israel to read his poems; and Kadya Molodowsky came from New York to recite her passionate verses. Chaim Grade delivered sophisticated lectures on the future of modern Yiddish literature. “The JPL hosted and cohosted virtually every major and lesser-known Yiddish writer to visit North America,” says Rebecca Margolis, associate professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures at the University of Ottawa, Canada, and the author of Jewish Roots, Canadian Soil: Yiddish Culture in Montreal, a definitive history of Montreal’s Yiddish-speaking community.

Thanks to the Yiddish Book Center’s online library, we know what these writers wrote. And thanks to archival photos, we know what they looked like. But how did they sound? What native inflections, cadences, and dialects breathed life into their words?

Sadly, the preservation of Yiddish audio has lagged behind the discovery and distribution of texts and images. Yet no one concerned about the fortunes of Yiddish literature can fully grasp its wit and wisdom without hearing it spoken aloud. That deep, fluid amalgam of Hebrew, German, and multiple world languages lands on the ear with a powerful jolt of recognition: we know it’s Yiddish even if we don’t understand it. And those born to the language spoke it with an easy vitality that can’t readily be replicated.

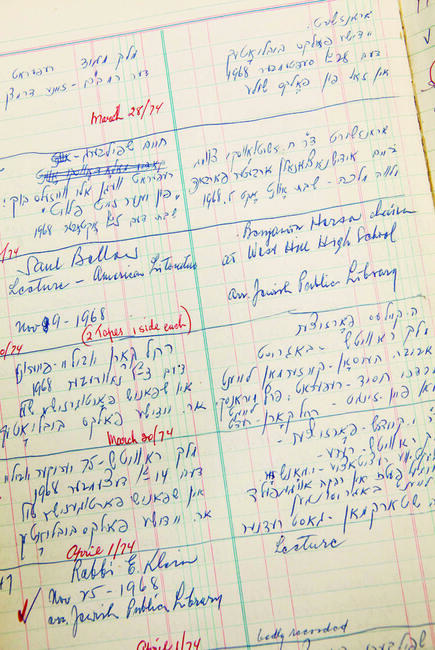

Now we have an unexpected opportunity to share the experiences of JPL’s large Yiddish audiences as they passed through a transitional moment in Jewish history. The Jewish Public Library began recording its public programs in the early 1950s; perhaps its staff foresaw that the Yiddish world was contracting, shifting from the status of a sweeping cultural force to that of a fascinating object of study. The big leather-bound log books of the programs, beautifully penned in Yiddish, English, and French scripts, list annual meetings, award banquets, concerts, and book-publication parties as well as names like Itzik Manger, Yankev Glatshteyn, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. There were multiday conferences on such topics as “Great Books of the Jewish People,” evenings honoring the anniversaries of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Night of the Murdered Poets, and, of course, political debates. Elie Wiesel came to speak, first in Yiddish, later in English. Marc Chagall appeared at the height of his career. There were Jewish humor nights, interviews, panel discussions. Flexible criteria for inclusion prevailed: in 1979, when Allen Ginsberg arrived, accompanied by a blaring harmonium, he invited his audience to chant “om” with him.

While the Jewish Public Library is now ensconced in a stately modern building on the west side of Montreal, and houses collections in Hebrew, Yiddish, French, English, and Russian, it still greets visitors to its archives with the heartfelt motto “You Don’t Have to Be Famous to Be Important to Us.” Zachary Baker, assistant university librarian for collection development at Stanford University, worked as a librarian at JPL during the 1980s, and he was aware that nearly all public events were recorded on reel-to-reel tapes, then the state of the art technology. Last year he urged the Yiddish Book Center to investigate the current status of the tapes and the possibility of digitizing them, since magnetic tape, long out of use, can’t serve as a permanent preservation medium. Baker says the quality and breadth of the programming is unmatched: “This is probably the largest and most readily accessible corpus of recordings of Yiddish authors [that exists] . . . a gold mine.”

Baker’s suggestion followed the successful completion of another joint project of JPL and the Yiddish Book Center: the Sami Rohr Library of Recorded Yiddish Books, a digitally remastered collection of fifteen full-length books on CDs, originally recorded onto cassette tapes by a volunteer corps of native speakers during the 1980s. Former Yiddish Book Center Fellows David Schlitt and Anita Christensen were in Montreal collecting hundreds of additional cassettes of the “talking books” and interviewing several of the readers when they learned through Baker of the program tapes. They consulted with then–executive director Eva Raby, bibliographer Eddie Paul, and other experts from the library. What they found were at least 1,500 reel-to-reels that hadn’t been circulated or listened to in decades, carefully inventoried and stored on the library’s shelves. Most were in excellent condition. “It was an epic moment” of discovery, says Schlitt. A sample set of reels loaned to the Center revealed clear, moving recordings that will bring to new generations the voices of the past.

Center President Aaron Lansky attended Yiddish programs at the Jewish Public Library on Saturday nights in the late 1970s while a graduate student at McGill University. “Montreal was like a North American Vilna,” he says, “a provincial city that had emerged as a true Yiddish intellectual center.” Montreal Jews from numerous countries, who had in common their traumatic flights from Europe as well as their mame-loshn, formed a sui generis Yiddish-speaking community whose distinct ethnic identity thrived outside the prevailing English and French cultures. Programs at the JPL, Lansky asserts, were challenging but never arcane; they addressed basic existential questions at the core of Jewish history. Lansky reveres the JPL as an institution like no other in the world for its inclusivity, its integrity, and its overt embrace of diverse Jewish traditions.

Lansky predicts that processing the 1,500 tapes will take about two years. MassProductions, a Boston-based company that specializes in digitizing fragile magnetic tapes, will transfer the three thousand hours of Yiddish content in real time as the data streams off the reels. As they are processed, the recordings will be posted online through the Internet Archive to join the Center’s Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library. They’ll also be accessible free of charge through Apple’s iTunes U.

Preserved in their unedited state, the JPL programs will retain their original resonance and spontaneity. Metadata, or cataloging records, will be added so that the files will be searchable by keywords such as author, title, date, and other fields. Together, the remastered recordings will be known as the Frances Brandt Online Yiddish Audio Library, thanks to a generous gift by Frances and Hubert Brandt of Lido Beach, New York, in honor of Mrs. Brandt’s eightieth birthday. Eva Raby regards the reel-to-reel initiative as a “wonderful partnership: a project initiated and carried through by the Jewish Public Library and made available to the Yiddish-speaking and Yiddish-loving world through the Yiddish Book Center.”

The Center is also committed to digitizing JPL’s rich store of English-language programs, which the library began to sponsor increasingly in the 1960s as Montreal’s Yiddish-speaking population started to shrink. (In the 1930s, says Rebecca Margolis, 99 percent of the city’s nearly 60,000 Jews claimed Yiddish as their first language; seventy years later, some 10,000 out of 92,000 Jewish Montrealers identified themselves as Yiddish speakers, a majority of them Hasidim who eschew secular Yiddish culture.) The library’s remarkable English-language collection features lectures by public intellectuals like Saul Bellow, Cynthia Ozick, and Susan Sontag. On the lighter side, there’s Leo Rosten delivering his joyful take on the Yiddish language and Victor Borge riffing on the piano. The tapes also include shmuesn—two-person conversations conducted onstage, such as one between Saul Bellow and the Yiddish scholar Benjamin Harshav.

Jordan Kutzik, a 2012 fellow at the Yiddish Book Center who is building the organization’s audio library, has done a preliminary transcription of all the logbook entries, which he calls “a who’s who of modern Yiddish writers.” Kutzik, a recent Rutgers graduate, points out the significance of repeat performances by many writers, whose successive views may track the precarious evolution of Yiddish literature over twenty, thirty, or forty years. One rare item is a recording of the famed poet, partisan fighter, and Yiddish music collector Szmerke Kaczerginski, who presented “An Evening of Ghetto Songs” in 1953—just two years before his death in a plane crash in Argentina at the age of 47. The Jewish Public Library’s tape may be the only extant recording of Kaczerginski lecturing in North America.

In the months ahead, as processing begins, the distinctive content of each program will surface. Voices we have never heard will surround us, enlighten us, and amplify our understanding of Yiddish literature and culture. As Chaim Grade passionately declared in a lecture at the Jewish Public Library in 1958, “Di yidishe literatur iz a hemshekh—Yiddish literature is a continuation.” His assertion just got louder.

Nancy Sherman is a former editor of Pakn Treger. Rebecca Margolis provided extensive research for this article. Black-and-white photographs courtesy Jewish Public Library Archives; color photographs by Michael Carroll.