Well Said: Kosher and Treyf: Geshmak iz der fish af yenems tish (The Grass is Always Greener on the Other Side)

- Written by:

- Asya Vaisman

- Published:

- Summer 2013 / 5773

- Part of issue number:

- 67

Zogt, vos esn yidn mit groys kheyshek

Bay yenem, tsi bay zikh aleyn in shtub?

S’iz pareve, nit milkhik, un nit fleyshik,

Nor a maykhl vos a yeder yid hot lib...

Gefilte fish!

(“Gefilte Fish,” Isadore Lillian)

Tell me, what do Jews eat so eagerly

At someone else’s house, or in their own home?

It’s pareve, not dairy and not meat,

But it’s a food that every Jew loves...

Gefilte fish!

At first glance, it may appear that the cuisines of Jewish communities in different countries have little in common. Even when it comes to ritually significant foods, the Ashkenazi kharoyses of Passover can hardly recognize its Sephardi cousin, charoset, which, though it plays the same role in the Seder, is made with starkly different ingredients. However, more unites the geographically dispersed dishes than first meets the eye (or should I say “mouth”?). Jewish food, whether Ukrainian borsht or Moroccan harira, traditionally conforms to the same set of defining regulations established by the laws of kashruth. While adapting the recipes of their non-Jewish neighbors, Jewish cooks have to keep the sour cream away from their beef and the milky rice pudding away from their lamb.

As in the song quoted above, kashres places an importance on the meat or dairy status of a dish to prevent the unlawful mixing of the two categories, and it dictates which foods are prohibited altogether from the culinary repertoire. The significance of the concepts of kosher and treyf to Jewish culture is reflected in the Yiddish language, which contains a number of expressions using these terms. Some of these expressions are indeed about food, such as “Az men vil gut boydek zayn, iz alts treyf” (“If you check thoroughly, everything turns out to be treyf”)—the devil is in the details, so to speak.

Other expressions extend the meaning of the terms, using them metaphorically: “Beser a kosherer groshn eyder a treyfener gildn,” which means “Better a kosher penny than a treyf nickel.” This phrase alludes to the original meaning of kosher as “proper” or “fitting”; in this case, the idiom states that a little bit of money earned legitimately and honestly is better than a lot of money acquired under dubious circumstances.

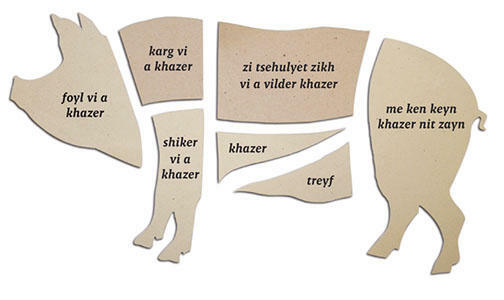

Equating unsavory activities and personality traits with treyf foods is a feature of a number of sayings concerning the most archetypally treyf food of all: the khazer, the pig. Someone who makes a big mess is compared to a khazer running wild in a garden. A guest is encouraged not to overstay his welcome lest he seem like a pig—“Me ken keyn khazer nit zayn—az men heyst geyn darf men geyn” (“Don’t be a pig—if you’re told to go, you should go”).

If someone is making too much noise, her neighbor might complain, “Zi tsehulyet zikh vi a vilder khazer!” (“She’s carousing like a wild hog!”). And a family member who’s not doing his fair share of the household chores might be dubbed “foyl vi a khazer” (“lazy as a pig”). An individual exhibiting too much chutzpah might elicit this exclamation: “Loz arayn a khazer in shtub, krikht er oyfn tish!” (“Let a pig into the house, and he’ll climb up on the table!”).

Even characteristics that one does not normally associate with real-life pigs are ascribed to the animal simply because of the necessity for the negative association. Thus a person who drinks too much is “shiker vi a khazer,” though I’m not entirely sure how often drunken pigs stumbled through the yards of Yiddish-speaking communities. One such comparison that has been particularly widespread is attributing stinginess to the khazer. Obtaining a contribution from a miser might be likened to pulling a bristle out of a pig, for instance—“Elehey fun a khazer a shtshetine oysgerisn.” There is also the more blunt folk saying “A kargn ruft men a khazer, un a shlekhtn—kelev,” meaning “A stingy person is called a pig, and a bad person—a dog.”

This list is by no means an exhaustive inventory of negative pig-related expressions (some of which are rather vulgar and perhaps not fit to print), but hopefully it does offer a sense of the distaste afforded the nonkosher animal. Though the language indicates that the pig was held in rather low regard by the Jews, not everyone was able to resist the smell of their neighbor’s roasting pork chops. And as the saying goes, “Az men est khazer, zol shoyn rinen iber der bord” (“If you’re going to eat pork, you might as well let the juices soak your beard”)—if you’re already breaking the law, you might as well really enjoy yourself. But don’t forget: “Der derekh hayosher iz ale mol kosher”—“The path of righteousness is always kosher.”

Asya Vaisman is director of the Yiddish Book Center’s Yiddish Language Institute. She has taught Yiddish at Indiana University and Hampshire College.