Di Yerushe

A Poem Celebrates the Yiddish Book Center's Founder

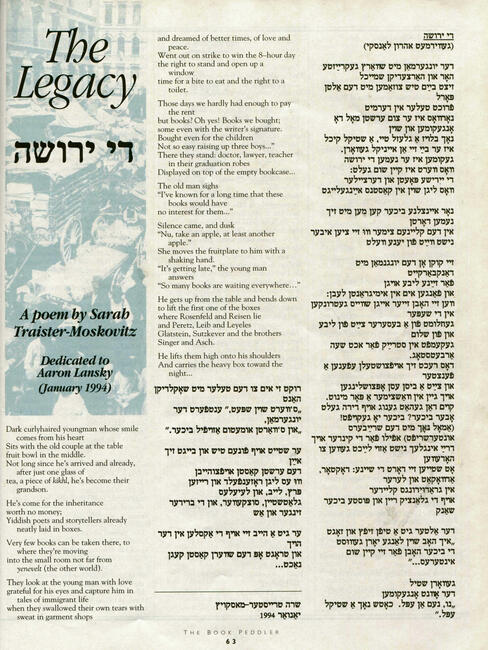

In the Spring 1995 issue of Pakn Treger, the magazine of the Yiddish Book Center, sandwiched between a galactic advertisement for Leonard Nimoy’s readings of Yiddish short stories and an ever-growing list of zamlers (volunteer book collectors) was the first—and possibly only—devotional poem to Aaron Lansky. Written in both Yiddish and English, "Di yerushe" ("The Legacy") rhapsodizes the “dark curly-haired young man/ whose smile came from his heart.”;

The poem narrates a visit by Lansky to an elderly couple in the last stages of their lives. (“Very few books can be taken there, to where they’re moving/into the small room not far from yenevelt.”) Lansky is there to receive an inheritance richer than money: boxes of Rosenfeld, Reisen, Peretz, and others. We meet the couple, but not their children. Their three sons, “doctor, lawyer, teacher," appear only in a graduation picture ominously displayed “on top of the empty bookcase.” The bookcase is “glantsik reyn,” dazzlingly clean—as if all traces of the past have been scrubbed away. The couple’s real gift to Lansky is the one that the children will not accept: their stories of immigrant life in America.

Predating Lansky’s memoir Outwitting History by almost ten years, the poem paints a portrait of his early days collecting books, both as that time actually was, and as the poet imagines it to have been. The poem is charming, unexpected, and somewhat mysterious; aside from a name, Sarah Traister Moskovitz, no further information accompanies the piece, or explains why it had been included in the magazine. My curiosity piqued, I set out to investigate.

As an archival assistant at the Yiddish Book Center, I’ve been reading through every single issue of Pakn Treger, from its inception in 1981 (when it was the newsletter of the “National Yiddish Book Exchange”) to the present day. I’ve encountered everything from translations of I. L. Peretz, Chava Rosenfarb, and Sholem Asch, to tales of Yiddish book swaps in Talinn and Riga set against a backdrop of late Soviet bureaucracy. Nothing jumped off the page quite like "Di yerushe." I was certain there was a story behind these words. When early attempts to reach the author by email failed, I sat down with pencil and paper, drafted a handwritten letter, stamped and mailed it, and waited for a reply.

A week later, the phone rang from an unknown number in California, and I was greeted with a "sholem aleykhem" from Sarah Traister Moskovitz. When I asked if she remembered anything about the poem she had written more than twenty years ago, I was surprised by her definitive yo!

"Di yerushe," she told me, marked her return to Yiddish after a two-decade-long absence. Traister Moskovitz was raised in a Yiddish-speaking household in Springfield, Massachusetts, just twenty-five miles from the Yiddish Book Center's current location in Amherst. She fondly remembered a childhood filled with Yiddish books. Her father had been a Yiddish teacher and principal of the Springfield Workmen’s Circle school. When she left home to study, however, she also left the Yiddish world behind, becoming first a kindergarten teacher and later getting her master’s and doctorate in human development and guidance. During this time, Traister Moskovitz worked as a family therapist, organizing and leading a group for child survivors of the Holocaust. From her work with this group, she would go on to publish Love Despite Hate: Child Survivors of the Holocaust and Their Adult Lives, an important text in the study of trauma and childhood psychology. She only returned to Yiddish when speaking with her family on the phone. After her parents passed away in the late 1970s, Traister Moskovitz lost this last connection to the language of her youth.

In December of 1993, Traistor Moskovitz heard Aaron Lansky deliver a lecture in Malibu on American Jewish literature, as part of the Yiddish Book Center’s annual winter conference. Over the phone, she recalled his energy and enthusiasm, as he regaled attendees with stories of Yiddish book rescues around the globe. The lecture was “a revelation” for Traister Moskovitz; the very next day, she told me, "Di yerushe" wrote itself—in Yiddish, the language she had not spoken since the passing of her parents, more than fifteen years earlier.

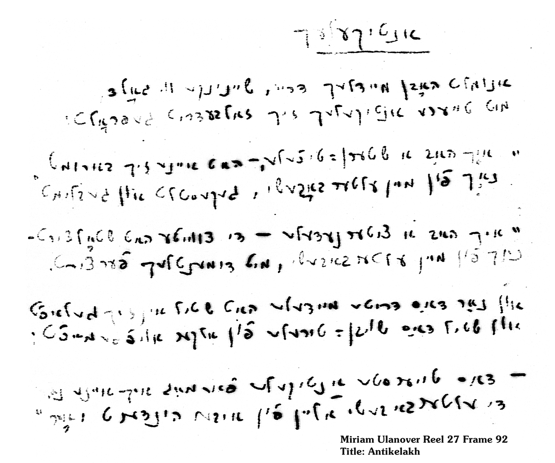

Inspired by Lansky's exuberance and love of Yiddish, Traister Moskovitz rekindled her deep connection to the language. In addition to writing "Di yerushe," she began teaching Yiddish classes, and in 1994 she traveled with her husband to Poland in search of her family’s roots. There she found a poem written in Yiddish by an anonymous writer hiding in the Warsaw ghetto, unable to leave their apartment. Traister Moskovitz discovered that the poem was part of the Ringelblum Archives, a collection of materials from the ghetto that had been secretly gathered and hidden away in old milk cans and tin boxes by a group of residents who called themselves Oyneg Shabes (the joy of Sabbath). After the war, most of the surviving documents were unearthed, but many had yet to be translated. Working with microfiche at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Traistor Moskovitz organized the poems and translated those that were legible. The project was a massive undertaking and today exists in full online under the title “Poetry in Hell,” bringing the voices of lesser known Yiddish poets such as Peretz Opochinsky, Miriam Ulinover, Simcha Shayevitch, and Yitzhak Katzenelson to an English-speaking audience. She also continued to write her own poetry and published a volume, Kumt tsum tish (Come to the Table).

It’s fitting that Traister Maskovitz chose to poeticize Lansky as a collector of lost writers and lost family stories. Faced with unknown poems by lost writers, Traister Moskovitz accepted the weight of their inheritance, their yerushe, and brought the poems to a new generation of Jews. She organized the poems by theme (nature, home, tradition, death, etc.), and in the process she made what could have been foreign intimate and familiar. She started by writing a poem about Lansky, by imagining what it means to collect, but the story ended with her transformation into another kind of zamler.

—Ozzy Gold-Shapiro