Why Read Sholem Aleichem?

- Written by:

- Jeremy Dauber

- Published:

- Fall 2014 / 5775

- Part of issue number:

- 70

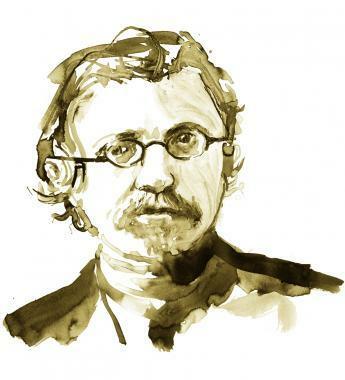

Over the past few years, I’ve spent a lot of time reading Sholem Aleichem. I just published a biography of him (The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem: The Remarkable Life and Afterlife of the Man Who Created Tevye—a great Chanukah gift, if you’re interested), and it was pretty much a requirement of the job.

As requirements go, it wasn’t an onerous one. But reading through the oeuvre of a remarkably prolific, not to say graphomaniacal, man—volume after volume of collected stories, novels, plays, and the occasional poem, to say nothing of the hundreds upon hundreds of letters he wrote to friends and family that were brilliant works of art themselves—you tend to think about why you’re spending the time reading this author’s work. And if you’re a teacher or a writer, you tend to think about why other people should spend the time, too.

I guess, when you come down to it, there are three main ways to read Sholem Aleichem—all of them valuable, all different, and all arguments for reading more of him. I experienced all of them, more or less strongly, over the course of reading his work and writing, publishing, and publicizing my book. Some—or all—may resonate with you. But I suspect that if you’re reading this essay, at least one of them will find purchase.

"His short stories and novels took on the very contours and currents of Jewish history."

The first—and in some ways the most direct, but in other ways the most limited—is to read Sholem Aleichem as a Jew. By this I mean first and foremost to read his work as Jewish writing. He was, after all, the man who in his short stories and novels took on the very contours and currents of Jewish history in one of its most dynamic periods ever, encompassing the Jewish Enlightenment, Zionism, Jewish involvement in socialist causes, the mass emigration from Eastern Europe, Jewish suffering during the Great War, and of course the attempt to maintain some sort of Jewish tradition in the throes of modernization and cultural upheaval—things that are of interest to anyone who cares about Jewish history and culture, then and now. It’s also possible, though, to read Sholem Aleichem as a Jewish person, if that’s who you are. To see if his theses—the importance of cherishing your own history and culture; the delights of Jewish language (Yiddish primarily, but Sholem Aleichem was also a great lover of Hebrew, and some of his earliest work was in that language); and the importance of the Jewish home, both in Yiddishland and in Zion—can illuminate your own ways of living in the world as a Jewish person today.

The second, wider way of reading Sholem Aleichem is as a reader. Many of Sholem Aleichem’s critics, after his death, accused him of being little more than a stenographer or tape recorder; they said his uncanny re-creations of the voices of a whole tapestry of Eastern European Jewish life were little more than a ventriloquism act. Even a cursory reading of the stories shows just how unfair this is—in fact, the stories are a bonanza for anyone interested in monologue, in literary game-playing with persona and personality, with narrative and closure, and with the careful and clever use of allusion. Sholem Aleichem—who took such care over his writing that he bit his fingernails to the bloody quick—was a writer’s writer, and anyone who takes pleasure in the crafting of great literature will rejoice in reading him. This is even the case for those who don’t read him in his original Yiddish, though some of the dizzying stylistic heights will be lost. But in the work of great translators, like Hillel Halkin, much still remains.

But ultimately, the third way to read Sholem Aleichem is, I think, the most important. And that is to read him, quite simply, as a human being. I handed in the manuscript of my biography to my editor literally hours before my wife went into labor and gave birth to our first child. Most of my thinking about Sholem Aleichem that followed, perhaps naturally, had to do with fatherhood: easy enough, since the character he’s best, and most justly, known for is a Jewish father himself. There’s a reason that Tevye—particularly in his later incarnation as a musical theater star—has been beloved by audiences from Broadway to Tokyo. That reason has to do with the brilliance and heart that Sholem Aleichem lavished on his creation, forging a character that tells us something about what it means to live, to love, to struggle, and to change. As human beings, as readers, and as members of a particular tribe and tradition—whatever that happens to be—we can’t get enough of that illumination, and Sholem Aleichem, in his Tevye stories (which you should read if all you know is Fiddler on the Roof; if you’ve read them before, read them again—you’ll get even more out of them on re-reading, I promise), provides it in spades. And his Tevye stories are just the tip of the iceberg.

Sholem Aleichem begged in one of his stories that he not be forced to tell his readers the ending, and he specialized in works of literature without a proper conclusion. I’m tempted to end this essay accordingly, in the middle of a sentence or thought, but that probably wouldn’t be fair to you, or to him. So instead I’ll suggest going to the Yiddish Book Center’s Digital Yiddish Library and finding some copies of his collected works to leaf through, or going to the Center’s bookstore and purchasing some of the stories in translation. However you encounter Sholem Aleichem—in whatever way, in whatever form—you won’t regret it.

Jeremy Dauber is the Atran Associate Professor of Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture at Columbia University. An alumnus of the Yiddish Book Center’s Steiner Summer Yiddish Program, he serves on the Center’s Board of Directors.