The Yiddish Book Center's

Wexler Oral History Project

A growing collection of in-depth interviews with people of all ages and backgrounds, whose stories about the legacy and changing nature of Yiddish language and culture offer a rich and complex chronicle of Jewish identity.

Norman Feinberg's Oral History

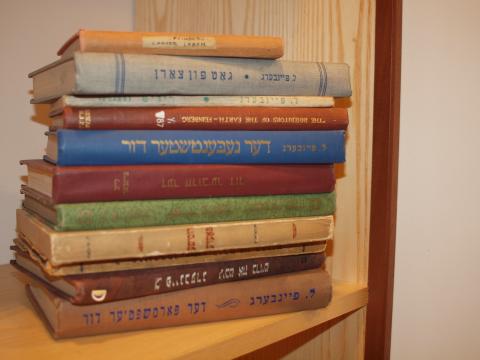

Norman Feinberg - retired college professor of music at Mercy College and youngest son of the late Leon Feinberg, Yiddish poet, author of many books, and regional editor for the Yiddish paper Der Tog - was interviewed by Christa Whitney on October 28, 2010 at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. Norman recounts how his father came to the United States, first at age 14, alone, to follow his father, and the second time after graduating from Moscow University, once the family had become disillusioned with Communism. He remembers how his father corresponded with his Aunt Rivke up until the 60s, when communication suddenly stopped. Norman's father was 50 years old when he was born, and he recalls that they did not have the traditional father-son bond of sharing a love of sports. He did, however, learn a lot from his father. He recalls his home as a very academically-oriented one, where being an intellectual was the norm rather than a choice. He recalls his father's schedule—how he used to have to be quiet during the day since his father would sleep in the daytime after writing all night. Norman fondly recalls a course on Yiddish literature on translation he took at a State University of New York, and the impact it had on him when he returned years later to find it blossomed into a full-fledged department. Norman's thesis on Sholem Ash had a surprising connection with his musical love, Bob Dylan, when he found out Dylan had played at a bistro owned by Sh. Ash's son (Moses) in his early years in New York. Norman recounts that, even amidst the criticism of Yiddish after the second world war, that his father said that Yiddish would never die. Norman recalls the many visitors that would come to the Friday night dinners that his mother prepared at their house. While he was too young to remember many of the specific people that visited, he particularly remembers Genya Nada, widow of Yiddish writer Moyshe Nada, and lover of Itsik Manger. Itsik Manger, the well-known Yiddish poet who suffered from alcoholism and depression, became a favorite of Norman's after Manger once bought him a giant all-day sucker candy at Coney Island. Norman calls his father a "renaissance man," and especially admired his father's talent and courage as a political journalist. He specifically remembers when his father predicted a resolution during the Cuban Missle Crisis. While the Feinberg family was not religious, they observed Passover. Norman describes his father as a non-observant man who embodied the essential moral tenants of religion. While his sisters went to Yiddish school, Norman insisted on going to Hebrew school with his friends. While it was more due to his first love rather than the education that he stayed at Hebrew school, he did have bar mitzvah. Norman remembers his father's travels all over the world as one reason why they didn't have much father-son bonding time. Norman reads one poem from his recent self-published book of 550 poems. "A Promise Unfulfilled Yet Magical" relays a story of when Albert Einstein was impressed by an equation his brother Gary, then 6 years old, had written out and asked his father to pass along when Leon went to a dinner honoring the eminent scientist. Norman describes his brother Gary as his surrogate father. Gary, a child prodigy, skipped straight to 3rd grade, and became the youngest full professor of Theoretical Physics in the history of Columbia University. Norman tells a story (one of his family favorites) of two elderly ladies' reactions upon seeing Gary, then age 2 and a half, reading the New York Times on the subway. Norman tells stories from a list of notes he had prepared prior to the interview. He tells of how his father was from the same town as painter Marc Chagall and actor Paul Muni. It was a joke with Leon's wife that if he had only accepted Chagall's offer of a painting, they would have been financially set for life. He recounts the one time he ever saw his father frightened—the family became the unintended brunt of a practical joke Gary's friend played when Leon opened a telegram reading "your son is dead." Norman remembers his father accompanying him to the hospital after a wrist injury on his 21st birthday as a rare moment of connection between the two of them. Norman concludes with a touching reflection on his inheritance of his father's love of writing: "I am my father's son."

This interview was conducted in English.

Norman Feinberg was born in Bronx, New York in 1947.