The Signs and Symbols of Ezra Korman, Detroit's Soulful Yiddish Poet

In the great borderless, world-spanning Yiddishland of once-upon-a-time, even Detroit had a Yiddish poet of renown.

And why not? There, too, masses of Jews settled during the Great Immigration from Eastern Europe—the number of Jews in the city leapt from 1,000 before 1880 to 35,000 in 1920, and with them grew institutions of Jewish life. (Many of these are described in Idishe institutsyes un anshtaltn in detroyt—Jewish Institutions and Relief Establishments in Detroit—published in 1940 by Detroit’s Jewish Welfare Federation.)

The Jews of the Motor City spoke and read local papers in their mame-loshn. One was called Undzer vort (Our Word): a socialist magazine populated with photographs of smiling toddlers in Workmen’s Circle schools and advertisements for May Day celebrations and quick lunches at delicatessens.

They attended Yiddish performances like the one in May 1915 at the Old Detroit Opera House, where members of the Detroit Progressive Literary Dramatic Club produced Sholem Aleichem's one-acter Agentn (The Insurance Agents). The classic writer spoke to the packed crowd and then retired for the evening to the nearby spa town of Mt. Clemens, where he stayed at the picturesque Elkin's Hotel. (My grandmother, Elizabeth Elkin Weiss, 1925-2015, whose great-uncle founded the hotel, used to hide on the landing there past her bedtime, listening to visiting Yiddish theater stars declaiming in the parlors below.)

And, to make a penny, Detroit’s Yiddish speakers dealt in scrap metal, laundry, bootleg alcohol . . . and yes, poetry.

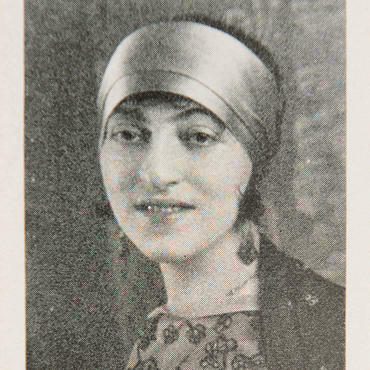

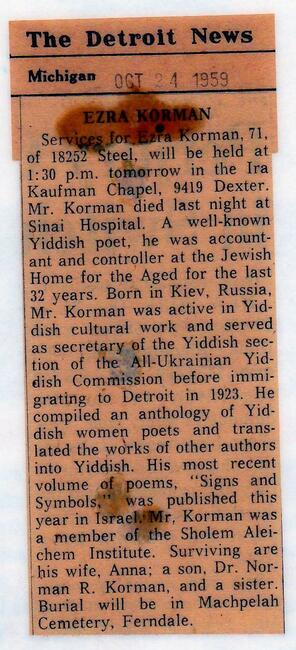

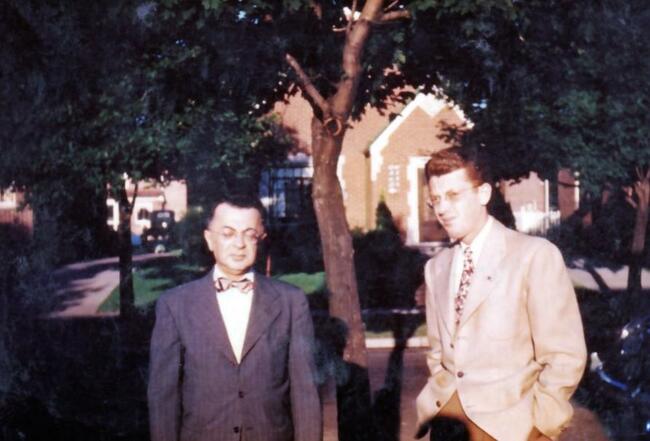

Ezra Korman was Detroit’s dean of Yiddish letters and, along with Shloime Schwartz in Chicago and Alter Esselin in Milwaukee, a pillar of Yiddish creativity in the Midwest. Born in Kiev in 1888, he immigrated to the United States in 1923, and died in his adopted city, Detroit, in 1959.

2.

But the Yiddish Book Center’s holdings testify to the diversity of Korman’s oeuvre and his tripartite literary talents: as anthologist-editor, as translator, and as poet. The bibliography also gives us a sense of Korman’s life. First, his translation of Heinrich Heine’s poetry, put out in 1917—before Korman had reached the age of 30—by Kiev’s avant-garde Kunst-farlag (Art Publishing House), an institution he cofounded. This work predated and was quickly eclipsed by the eight-volume Yiddish translation of Heine’s writing that was published in New York the following year.

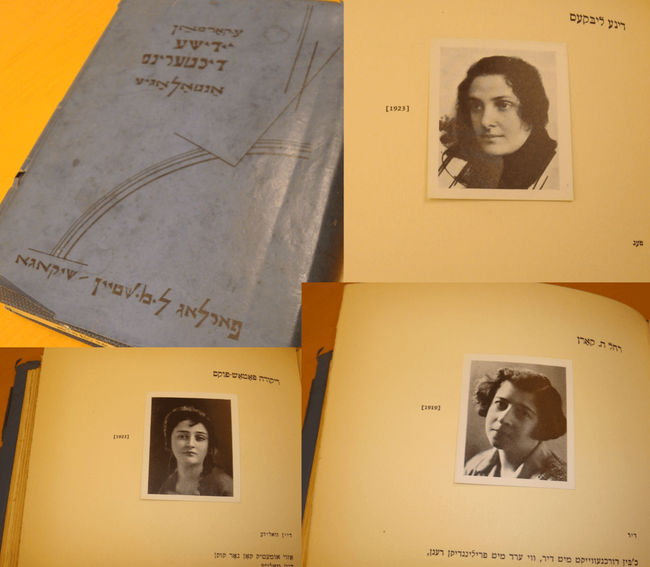

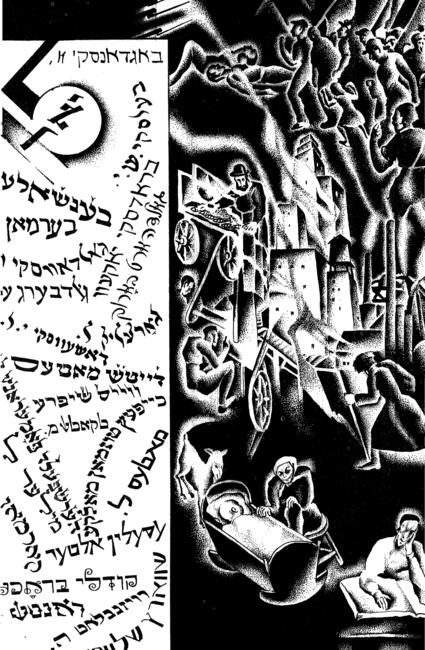

In a display of sympathy with the struggle of the working classes, Korman then published his first anthology, In fayerdikn doyer - zamlung fun revolutsyonerer lirik in der nayer yidisher dikhtung fun ukrayne (In Fiery Duration: Collection of Revolutionary Lyrics in the New Yiddish Poetry of Ukraine) (Kiev, 1921), and its expanded version, Brenendike brikn (Burning Bridges) (Berlin, 1923). At the same time, in his native Kiev and in Warsaw, he was helping to establish the Kultur-lige, a prominent, socially involved organization focused on the promotion of Jewish culture, arts, and education.

While in Warsaw, in 1923, his wife Anna gave birth to their only child Nokhem, later Norman Korman (the poet’s ear for rhyme not being limited to his poetry, it would seem). Around the same time, two more of Korman’s translations were published in Warsaw and Berlin: a drama (the Dutch-Jewish playwright Herman Heijermans’ Op Hoop van Zegen—Hoping for Luck; or in Korman’s less, well, hopeful rendering, Farloyrene hofenung—Lost Hope) and a Russian history of Jews in the Bolshevik Revolution, bringing Korman’s running total of translation-origin languages at this point to three. (Years later, proud of his new Midwestern surroundings, he would translate Chicago poet Carl Sandburg into Yiddish—and, as it happens, his own poetry into English . . . more on this later.)

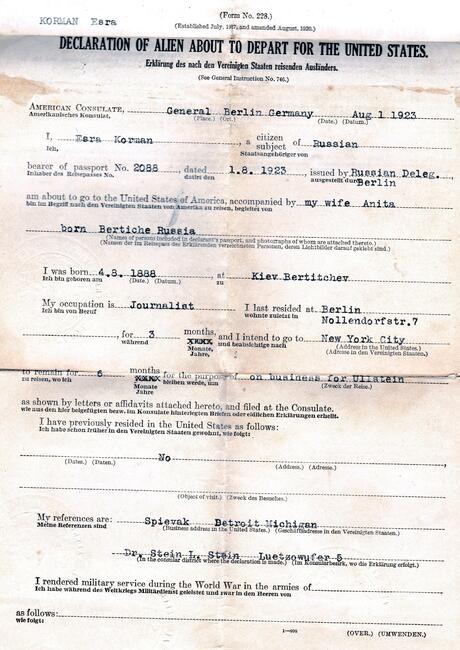

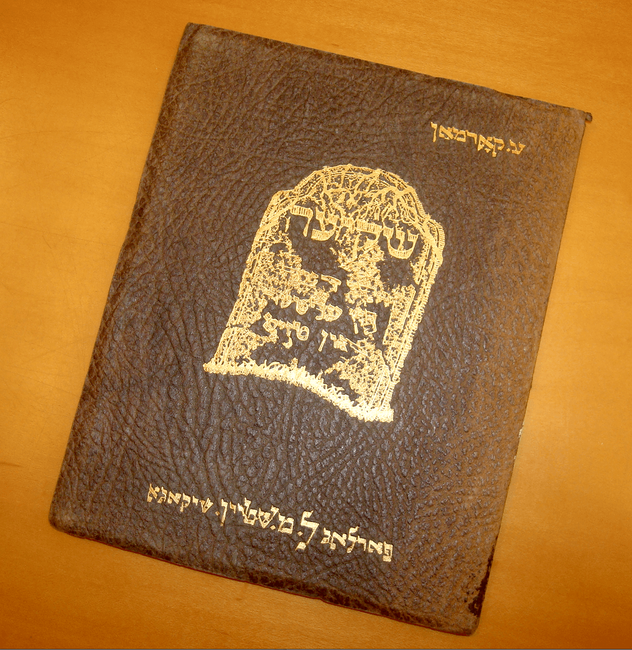

In 1923, Korman immigrated to the United States, traveling on the S. S. Tyrrhenia and noting “Journalist” as his occupation on his pre-departure papers. He and his young family soon made their home in Detroit, where Anna would become a registered nurse at Harper Hospital. In 1932, the first book of his own poetry was published: Shkie: lider fun elter un toyt (Sunset: Poems of Old Age and Death), this time dedicated to his father’s memory.

Published in Chicago (but with the copyright belonging to Korman, in Detroit), the small book, bound in leather with a tombstone embossed on the cover in gold, is filled with reflective, rhythmic word-pictures on death and dying and what comes after. A standout is “Levaye” (“Funeral”), in which mourners gather to silently say goodbye, knowing they “ale veln zikh bekorev dort bagegenen” (“they will all soon meet there”)—until “eyn kol,” one voice, “rayst zikh,” tears through the silence, wailing. Throughout the book, snow and frost are recurring motifs, chilling the body and the soul, or blanketing the earth and its memory. No wonder, for Korman on the last page tells us of these poems’ provenance: “Vinter 1929, detroyt.” Winter is a cruel season in that city. When sitting down to compose, snow is the closest—often the only!—image at hand.

But Michigan is a place where all four seasons are clearly, richly defined, each with its own color and its own emotion. Korman was moved by all of them, as we see in a poem from 1933, when his work was featured in an anthology meant to give the public an impression of the breadth of Yiddish creativity throughout America, not just in New York.

In this Antologye - mitvest-mayrev, or From Midwest to North Pacific: Anthology of Yiddish Verse, Korman, in addition to receiving a section of his representative urban poems, is given the special honor of contributing a poem in memory of the book’s dedicatee, New York poet Moyshe Leyb Halpern. In this piece, printed in the introductory pages of the anthology, Korman presents a favorite notion, that the departed are not truly so, if their words be only read again, and their spirit remembered:

“Nit gloyb, az toyt iz moyshe leyb. / Es lebt zayn umru nokh, / zayn vilde kraft, / zayn dreyste tsung, / fun lid zayn shtarker shvung. . .” —“Don't believe that Moyshe Leyb is dead. / His restlessness lives, / his wild power, / his audacious tongue, / the powerful swing of his song. . .”

The most fun poem, though, is Korman’s cacophonous, scent-and-sound filled pæan to spring in Detroit, “Friling-dzhez” (“Springtime Jazz”). The season's sudden clash of fragrance and color becomes, synæsthetically, jazz music, of the sort Korman might have heard drifting from the city's streets and speakeasies. At the time, the center of Jewish settlement, Hastings Street, was becoming a key thoroughfare of Black Bottom, Detroit’s African-American neighborhood. In “Springtime Jazz,” the idioms of both groups harmonize in one multichromatic melody.

Springtime Jazz

The sun beats jazz on its cymbals

in the blue-dyed sky.

With wild springtime rhythms,

lilac scents the bright outside.

Spring’s tuning the slenderest strings

of all its violins

and answering heaven’s trombone

in a song with sun therein.

The polished brass of horns drags

out a wah-wah shofar-blow.

And copper from the sunshine jazz

flames up in fire-bows.

(Yiddish from p. 153 of 1933’s Mitvest-mayrev, with the last verse as it appears on p. 79 of 1959’s Tseykhns un tseyrufim. Unless otherwise noted, all translations in this article are by Michael Yashinsky.)

פֿרילינג־דזשעז

די זון אױף טאַצן שפּילט אַ דזשעז

אין אױסגעבלויטן הימל.

אין העלער דרויסן שמעקט מיט בעז,

מיט פֿרילינגדיק געװימל.

דער פֿרילינג שטעלט די פֿידלען אָן

אױף דער דינסטער סטרונע

און ענטפֿערט הימלשן טראָמבאָן

צעזונגען און צעזוניקט.

און ס'קלינגט פֿון האָרן רײנער מעש —

אַ תּקיעה אױסגעצױגן.

און קופּער פֿון דעם זונען־דזשעז

פֿלאַמט אױף אין פֿײַער־בױגן.

Korman would not publish another book of original poetry until the final year of his life. In the intervening years, he would continue to edit, forge connections between Yiddishist centers in the Midwest and Canada, and, in his usual fashion, initiate innovative cultural projects, like his international journal Heftn - far literatur, kunst, un kultur (Notebooks: For Literature, Art, and Culture) (1936–37), based in both Detroit and Montreal. Nor did he stop translating. In 1946, he self-published his translation, into Yiddish, of a selection of the revered Russian poet Sergei Yesenin’s verse. Korman’s only book printed in Detroit, the cover page even gives his own address in the city, 18252 Steel Avenue.

3.

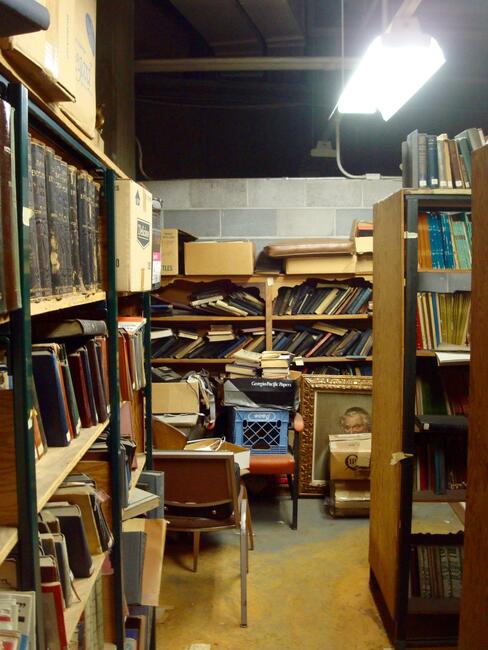

Korman and I share Detroit. On a recent trip home, I found further traces of his life in the city. As part of a fellowship sponsored by the Detroit-based Eugene Applebaum Family Foundation, I was in town giving lectures on Detroit Yiddish culture at Wayne State University, Frankel Jewish Academy, and Congregation Shaarey Zedek. I also undertook archival work at the latter, one of the area’s oldest synagogues, which in 1962 moved from Detroit to its current location in a soaring tent of concrete in the suburb of Southfield. At that time, the old location’s Yiddish library was brought in its entirety to the new building’s basement. For over half a century it remained there, unseen. But the enterprising new director of the shul's Berman Center for Jewish Education, Wren Beaulieu-Hack, has been curious about its contents. Now, appreciative of their cultural, historical, and spiritual worth, the shul is working to recover these old Yiddish books and restore them to a dedicated place in the recently renovated library. I was engaged to work on the project, to excavate this basement tel and separate out the Yiddish volumes, then catalogue and describe them.

Wading through the fascinating miscellany of the vault, past mountains of Goliath-sized soup pots and set dressing for what appears to have once been a Biblical masque (a wooden well painted to look like stone, a rocking billy goat), I was greeted by this marvel: nearly every other Yiddish volume in the collection bears Ezra Korman’s bookplate. Many of the tomes were personally inscribed to him by their authors, like Ida Maze of Montreal, who writes in a copy of her “Mother and Children’s Poems” to her “liber fraynt un liber dikhter ezra korman” (“dear friend and dear poet Ezra Korman”), his wife Anna and their “dear child.” There are heaps of periodicals, too, all with their address labels made out to Ezra Korman on Steel Avenue—among them, the New York communist magazine Der hamer (The Hammer), Detroit’s Undzer vort, the Midwestern literary journal Shikago, and Undzer veg (Our Path), the organ of Holocaust survivors living in the British zone of postwar Germany, its first issue published in a displaced persons camp. In many of them, Korman’s own articles appear.

But literary pursuits were not the whole of his daily work, I have lately learned. The Leksikon fun der nayer yidisher literatur (Biographical Dictionary of Modern Yiddish Literature) gives but a few sentences on his life; likewise, his biographical entry at the back of the Midwest anthology. My understanding of Korman has been enriched by the artifacts of his life, by the poet’s own words, and by a telephone conversation I had recently with Nina Korman, 49, the poet’s granddaughter and only living descendant.

In our chat, Nina told me that, of course, her zeyde did not live by Yiddish cultural activism alone—who could? For most of his years in Detroit, he earned regular wages as the comptroller of Detroit's Jewish Home for the Aged, where Anna also worked as a nurse. The detail gives an added nuance, a daily lived experience, to Korman’s litany of poems dwelling on the latter stages of the life cycle—of, as the first book of his poetry is subtitled, “Old Age and Death.” By the time of its publication, he would have already been working at the Jewish Old Folks Home (as the institution was then called) for five years.

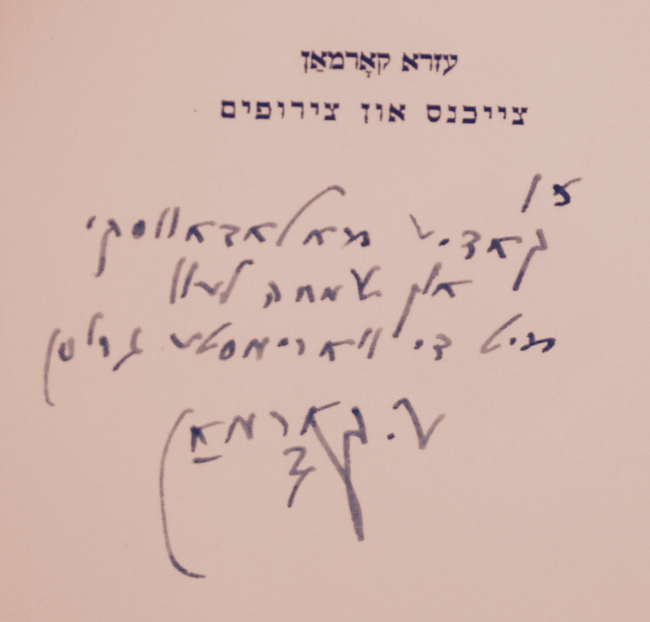

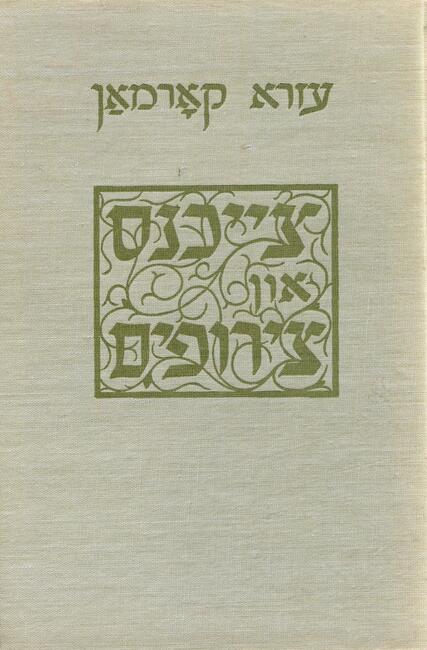

Ezra Korman died only just after his long-anticipated final volume of poetry, Tseykhns un tseyrufim - lider un poemes (Signs and Symbols: Verse and Long Poems) was published by the prestigious Y. L. Peretz Farlag in Tel-Aviv, in 1959. Though translated as such on the inside cover for the purpose of a pleasing alliteration, “tseyrufim” are more than “symbols.” They are, according to Kabbalistic tradition, combinations of Hebrew letters which, when arranged and rearranged, possess mystic powers of creation and recreation. The tone such a title strikes is unmistakeable. To Korman, poems are not mere incandescence—they are incantation. They have the power not only to sum up, but also: to summon.

This is an ample collection, including never-before-published pieces and revised versions of ones already seen. It was first previewed in the opening pages of his 1946 translation of Yesenin’s poetry: “Greyt tsum druk: Tseykhns un tseyrufim - lider” (“Ready for printing: Signs and Symbols - Poems”), though this would not come to fruition until thirteen years later. The collection’s gestation was protracted, and its birth momentous—shortly after Korman’s words saw the light of the world, he left it, as if he had built his monument and were satisfied with it. The Yiddish Book Center has in its collection a copy the poet enthusiastically inscribed to Kadia Molodowsky, whose work he had some thirty years earlier published to great acclaim in his anthology of women poets: “Tsu kadye molodovski un simkhe lev mit di varimste grusn, e. korman” (“To Kadia Molodowsky and Simkhe Lev [her husband] with the warmest greetings, E. Korman”).

In this wide-ranging book, the poet speaks in his quietly cadent, linguistically resourceful (particularly in his use of Hebraisms), deliberate but emotional manner on such topics as the ravages of Holocaust in the lands of his birth, Elijah the Prophet and other figures of Jewish legend, intermarriage (in a provocative, ambiguous poem titled “Perl un kreln”—“Pearls and Beads”), and, of course, philosophies concerning life, death, and the life thereafter.

For all his rumination on this theme, at the end of his life Korman claimed to have gained no more than the slightest idea of its great mysteries. A sad thought, perhaps, but one we may comfort ourselves with—even minds and hearts tuned extra-sensitively to receive the waves of the world may not endure to grasp them. This he expresses in the piquantly epigrammatic “A remez” (“A Clue”), a poem worthy of being remembered:

A Clue

A whole life long in search of truth,

and I only found a clue,

a mere splinter, a suspicion,

of the truth — a premonition.

אַ רמז

אַ לעבן לאַנג געזוכט דעם אמת

און געפֿונען נאָר אַ רמז,

נאָר אַ שפּילטער, אַ דערמאַנונג,

פֿון דעם אמת נאָר די אַנונג.

(p. 205 of Tseykhns un tseyrufim)

4.

In his wake, Korman left a world of words, and one woman, Nina, seeking to find her way in it. She never met her grandfather, having been born to Norman and his Cuban-born wife, Mimi, some years after Ezra’s death. Though Norman, a physician, kept her grandfather’s books in their house, he seldom spoke of his father’s achievements. Nina grew up barely aware of who Ezra had been; still, she enjoyed a very warm relationship with her grandmother, Anna, who moved to Miami Beach to be near the family after Ezra’s passing. Nina knows Spanish but no Yiddish. She has never visited Detroit. But like Ezra, she is a writer, working primarily in journalism.

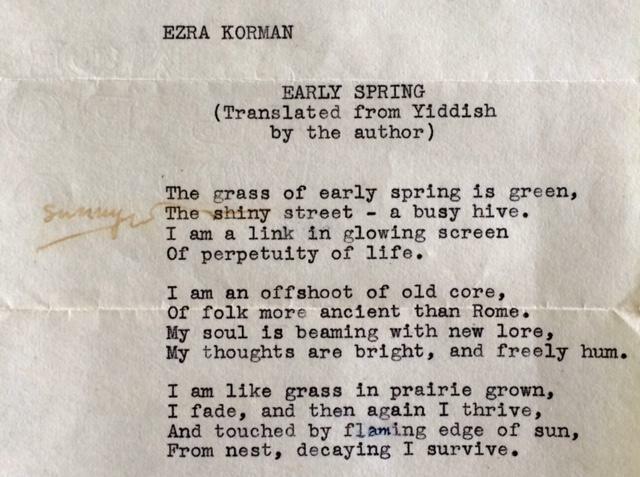

Lacking Yiddish, she has only read one of Korman's poems, one he himself translated. She found it folded inside her father’s wallet after his death. Norman had apparently typewritten it himself, folded it tightly, and had carried it with him for many years, his father’s words ever close beside him. It is another of the poet's reflections on spring in the city.

While we spoke, I translated another Korman poem for Nina, one addressed to her own father, titled “Tsu mayn yingl” (“To My Boy”). In it, the speaker cautions his son, whose ear is pressed to the latest serial dramas rumbling forth from the radio, against growing up too quickly, and involving himself too soon in the cruel dramas of the world. As she wrote to me later in an email, hearing the poem strengthened her resolve in her mission of rediscovery:

“To hear the strength of his literary voice, how much of his true self he was able to communicate in just the scant two poems I’ve experienced in English has certainly emphasized the importance for me of finally becoming fluent in Yiddish. . . . only those who can read my grandfather’s language—and who take the time to read his work—can really know how substantial his contribution was or, better said, is.”

In her home, Nina keeps artifacts of Ezra Korman's life: his books, an LP recording of his memorial service in Chicago, his boat ticket to America and immigration papers, and his Yiddish typewriter, which her father had once wished to give to the elderly Isaac Bashevis Singer, then living in nearby Surfside, Florida; Nina hotly refused, having been told that her grandfather had preferred the novels of I. J. Singer, the elder brother of Bashevis. But her father, too, once unexpectedly rose to the defense of Korman's legacy. Nina remembers a scene from the 1980s, when she heard her father “talking on the phone, very loudly, almost yelling.” At the end of the verbal “battle,” he slammed down the receiver. “Who were you talking to?” Nina asked Norman. “Irving Howe,” he answered, bitterly. Norman had been chiding the scholar for not including Korman in his recently published Penguin Book of Modern Yiddish Verse. The great anthologist himself no longer had a place in the latest anthologies.

Of these objects and these memories, this semi-forgotten legacy of a once-renowned poet, Nina told me the following:

“Part of the problem with being the only heir . . . of somebody like my grandfather is you have all this stuff. And you can’t read it. . . . Hopefully I will read it eventually. . . . But you don’t really know what to do with it. . . . What am I going to do with this? Where is it going to go when I’m gone, because I don’t have kids, and I don’t think I’m going to have kids at this point in my life. . . . That’s a dilemma, definitely. . . . I don’t want to just take it to the incinerator, my gosh! No way. . . . Who will take it, this kind of orphaned stuff?”

Her grandfather’s poem “Gezang nokh di niftorim” (“Song for the Departed”), printed in his Tseykhns un tseyrufim (p. 105) shortly before he died, could serve for a bit of advice to her, and to all of us who wonder what to do with the legacies we have been left: hold them dear. Even if we cannot read every word, or recognize every face in every yellowed photograph. Only uncover them, and keep them where they can be found again. Only peer inside them—the damp cellar, the torn valise, the wallet with a secret note inside, softened by time and touch—and they may bring us untold treasures, animating spirits we had thought lost forever. Only blow the dust off of a tseyref, and its letters may shift and glow in ways unimagined. . .

Song for the Departed

They are gone forever, here no more,

none who’ve departed remain.

Only dust is here, like sand on the shore

it settles thickly on their graves.

Thus our valley empties out,

wind felling trees like knights have cut them.

The shepherds have vanished from the great long-ago,

those keepers of clan and of custom.

Who like them will arrive, in some dazzling light,

to bear the legacy they left?

Our valley would surely bloom once more,

as life would overcome death.

The paths of the buried would reach to forever,

to fullness and worth beyond hours,

advancing from their earthly days,

from sands of the desert to stars.

Today they are covered at the world’s dark edge,

but all that is ash does not as dust reappear.

From under the dirt, from under its sludge,

there may rise the wealth of Ophir.

געזאַנג נאָך די נפֿטרים

זײ גײען אױף אײביק, אױף אײביק אַװעק,

ס'בלײַבט קײנער נישט נאָך די נפֿטרים.

נאָר שטױב קלײַבט זיך אָן, װי דער זאַמד אױפֿן ברעג,

און לײגט זיך געדיכט אױף די קבֿרים.

אַזױ אױסגעלײדיקט עס װערט אונדזער טאָל,

דער װינט רײַסט די בײמער, װי ריטער.

ס'פֿאַרשװינדן די שעפֿער פֿון גרױסן אַמאָל,

פֿון דורות און שטײגער די היטער.

װער װעט, װי זײ, קומען אין בלענדיקער שײַן,

װער זײער ירושה װעט אַרבן?

עס זאָל װידער בליִען דער טאָל, ער זאָל זײַן,

דאָס לעבן זאָל גובֿר־זײַן ס'שטאַרבן.

צו נצח געצױגן זיך האָט זײער װעג,

צו שלמות, צום אײביקן קרן.

זײ זענען געגאַנגען פֿאָרױס פֿון די טעג,

דורך זאַמדן פֿון מדבר צו שטערן.

הײַנט דעקט זײ די ערד צו בײַם פֿינצטערן ברעג,

נאָר ס'װערט נישט אַלץ עפֿר ואפֿר.

פֿון ערדישער שױם, פֿון אונטער איר דעק

װעט אױפֿבליען ס'גאָלד נאָך פֿון אופֿיר.

—Michael Yashinsky, Applebaum Fellow at the Yiddish Book Center