Melech Ravitch: My Friend Bertha Kling

— Melech Ravitch, translated by Abigail Weaver, 2019/2020 Yiddish Book Center Fellow.

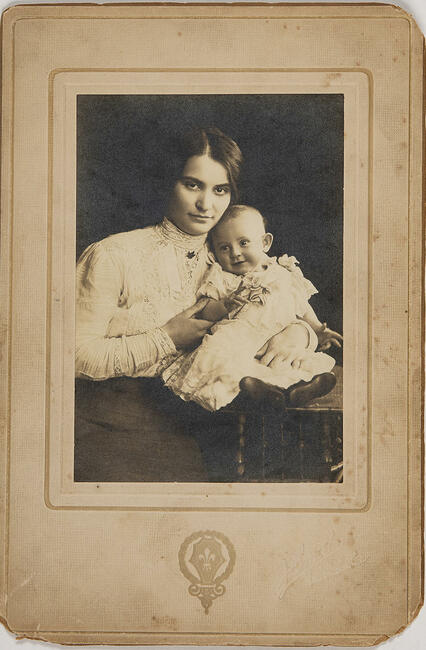

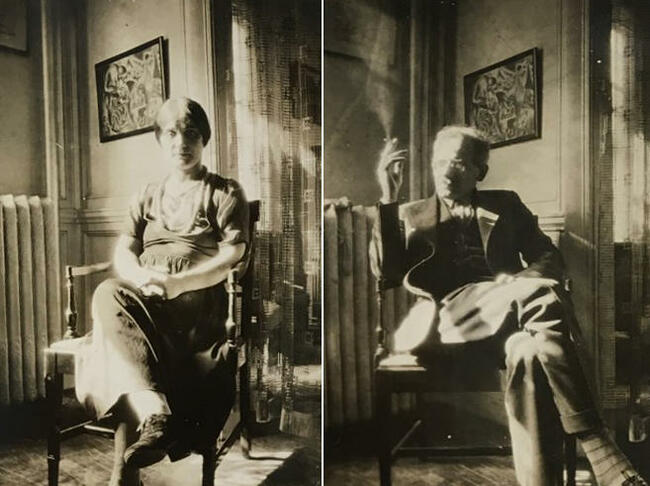

Bertha Kling was raised by her grandparents in the shtetl of Novoredok (now Navahrudak in Belarus) and came to America at the turn of the century in her teens. She married young, to Yekhiel Kling, a medical student and fellow Yiddish speaker. By the late 1900s, they had set up home in their first apartment in the Bronx, which soon became an informal social center for a wide circle of young immigrant writers and intellectuals. Bertha was an admired and acclaimed singer of Yiddish songs who later established a reputation as a poet.

Both Bertha and Yekhiel were fondly remembered in prose and verse by a wide variety of writer friends. In the course of this blog, we will feature several of these tributes, newly translated into English. This one is by Melech Ravitch, a well-known poet and memoirist, who was also a tireless cultural activist and traveler. As such, Ravitch was perhaps the best connected of any twentieth century Yiddish writer. He knew the Klings well and corresponded with them over many years.

This piece, written in 1957, appears in Ravitch’s monumental five-volume work, My Lexicon, which consists of hundreds of individual portraits. The entries are affective, poetic, and deeply personal character sketches of the Yiddish luminaries within his wide circle, based on his own friendships and encounters. This sketch provides a heartfelt introduction to Bertha Kling in its treatment of her biography and poetic style, and especially in its description of her leadership in the literary scene as a salon organizer and mentor. Melech Ravitch paints a portrait of a deeply beloved figure who was closer than family to many of the writers in her circle.

Bertha Kling

Born 1886 in Novoredok, southeast Poland; in America since 1900; died August 9, 1978.

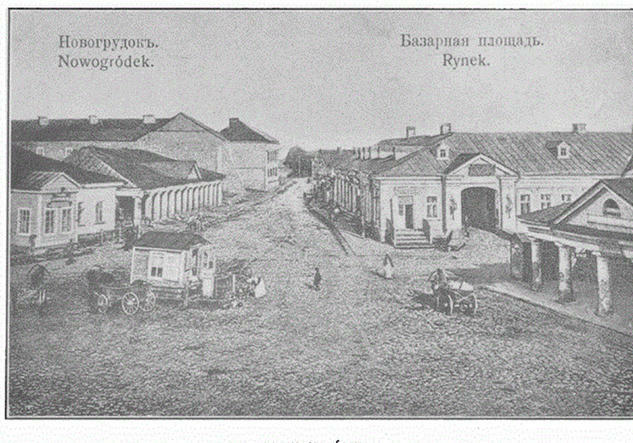

Novoredok is a little town in southeast Poland, now within the borders of Byelorussia if I remember correctly. I was in that town only once, around 1925, but it always remained somewhere in my psyche. Although my memory of it is fading, I do recall these details: the ancient white walls, five feet thick, around the low houses in the marketplace; ruins where owls whisper to the pitch-black night, where crows linger by day—and where legends abound through every season. I remember an old fish pond, and locked garden gates.

In the Polish language, Novoredok is called Nowogródek. Adam Mickiewicz, Poland's greatest—and for all his realism, also most mystical—poet grew up there. Novoredok is present in his poems and ballads, and through these ballads its presence is felt in all Polish Jewish verse.

The town was home to a famous yeshiva, and to the writer Chaim Grade when he studied there. And Bertha Kling was also from Novoredok.

Not only did this heritage leave a deep impression on her, it formed the very essence of her nature. If she had devoted herself entirely to writing, she would undoubtedly have been a prolific balladist of great renown. But Bertha Kling consciously chose—being a wise and worldly woman—to focus more on embodying her poetry and singing songs than writing.

In the prosaic urban setting of Jewish New York, it took someone with a special sisterly feeling to establish such a circle, such a home, such a community, to create the Novorodeker small-town, folks-poetic atmosphere without which no real literature can be created. Together with her husband, Dr Yekhiel Kling, Bertha Kling took this role upon herself. She was the sister, or one might say the big sister, of the group of poets known as the ‘Young Ones’ (Di yunge).

I first saw her in 1934—a light-brunette, of average height. Her gaze was gentle, her hands were gentle, her hair with its signature middle part was gentle, and above all, her voice was gentle. I thought to myself: “How can one person exhibit so much gentle patience? Is it just an act?” But after a few days I had my answer: It wasn’t an act, far from it. Her behavior was principled and a conscious choice, placing it on a higher ethical plane than simple kindness.

Even a regular sister is not always good to her brothers—let alone to her brother-artists, each of whom secretly aspires to wear the crown. This is all the more true of a sister not related by blood, but rather born to a capricious muse whose children spring directly from her forehead, like in the Greek myths. It took a great deal of conscious effort and will for Bertha to be good to her artist-brothers. But you don’t have to take my word for it. Here is one of her poems, "To a Braggart."

I am the weakling

Between us, so weak –

I can keep quiet

And let you speak.

But I am proud enough

As you can see –

To tilt my head and smile

When you look down on me.

איך בין דער שװאַכלינג

צװישן אונדז בײדן;

איך קען שװײַגן

און לאָז דיר רײדן.

בין איך אָבער שטאָלץ גענוג

אײַנצובײגן מײַן קאָפּ,

און שמײכלען –

װען דו קוקסט צו מיר אַראָפּ.

Bertha Kling’s poems are not composed of verses in the literary sense of the word. They are more like lyrics to be sung . . . . . miniature librettos to miniature folk-operas. This description may seem far-fetched, but that’s how it is. Bertha Kling had an understated voice, like a heavenly echo. As a result she could perform a song, especially a folk-style art song, like no other. On one occasion, a professional singer came over, a Jewish woman from England. Upon hearing Bertha sing she said, with a sigh that sounded like it was plucked on a lyre:

“Oh, if only Bertha had my voice, or if only I could perform folksong with her passionate spirit—either one of us could take the whole world by storm . . . ”

But Bertha Kling only conquered the hundreds—or maybe thousands—of gatherings of writers and literati that she organized in her home over the course of a half-century.

Bertha published three slim volumes of poetry, one with a preface by J. I. Segal. All in all, maybe a thousand rhythmic lines, hardly using rhyme and rarely forced into regimented cages of stanzas. Bertha surely had tunes in mind for most of her poems. If only she had divulged them.

Were I forced, by some grotesque miracle, to compile a prayer book, I would include the following Bertha Kling poem as a prayer. I would also call upon a Yiddish musician for accompaniment, to set the poem to a powerful melody:

Do not forsake us, God,

When we forsake the forsaken.

Do not condemn us, God,

When we condemn the condemned.

Do not afflict us, God,

When we afflict the afflicted.

Sanctify us, God,

When we sanctify the sacred.

Do not save us, God

When we save the saved.

פֿאַרלאָז אונדז נישט, גאָט,

װאָס מיר פֿאַרלאָזן פֿאַרלאָזענע.

שעלט אונדז נישט, גאָט,

װאָס מיר שעלטן פֿאַרשאָלטענע.

נישט פּײַניקן אונדז, גאָט,

װאָס מיר פּײַניקן געפּײַניקטע.

דערהױב אונדז, גאָט,

װאָס מיר דערהױבן דערהױבענע.

העלף אונדז נישט, גאָט,

װאָס מיר העלפֿן געהאָלפֿענע.

Whether or not it ends up in a prayer book, this is Bertha Kling’s strongest poem, although quite different in tone and theme from her other work. It’s also one of the most powerful poems in all of Yiddish literature. If you were to make a full accounting, this poem is composed of no more than twelve distinct words. But these twelve words reveal the innermost depths of the heart—as a lightning strike illuminates the night.

Notes:

Ravitch’s birth date for Bertha Kling—1886—is one of many dates around the mid-1880s that appear in different accounts and official documents.

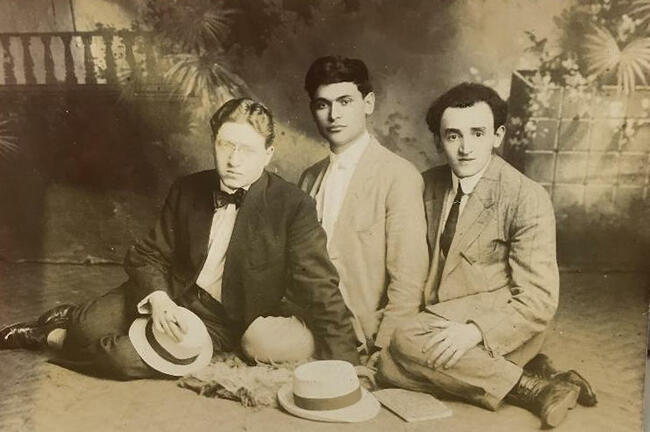

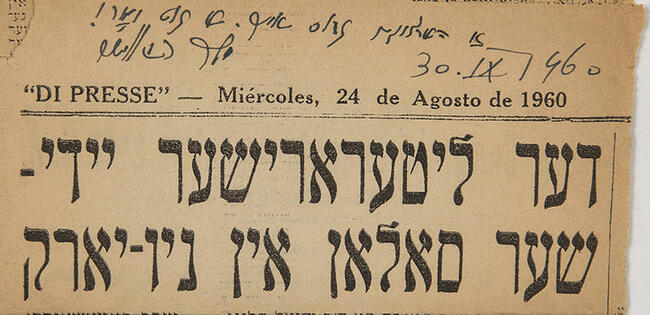

Di yunge was American Yiddish literature’s first modernist group, founded by young immigrants like Reuben Iceland, David Ignatoff, Mani Leib, and Zishe Landau. Shoemakers, painters, and paper-hangers by day, they were poets, story writers, and devotees of world literature at night. Many in the group were close friends with Bertha Kling, and she encouraged their creative efforts, hence Ravitch’s description of her as their ‘big sister.’ The description of David Ignatoff in the photo caption comes from Gerald Marcus’ translation of Iceland’s memoir, From Our Springtime.

J. I. Segal was associated with Di yunge in the 1920s and is considered Canada’s foremost modernist Yiddish poet.

Read Ravitch’s text in the original (pp. 251–3 in the book; pp. 255–7 on the scroll-along reader)