Miriam Karpilove, Photographic Retoucherin

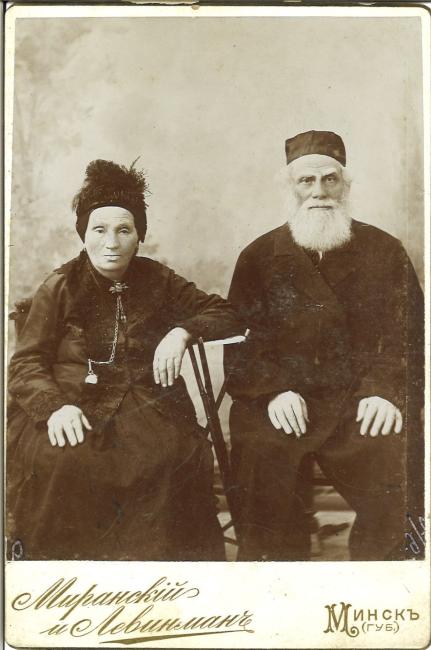

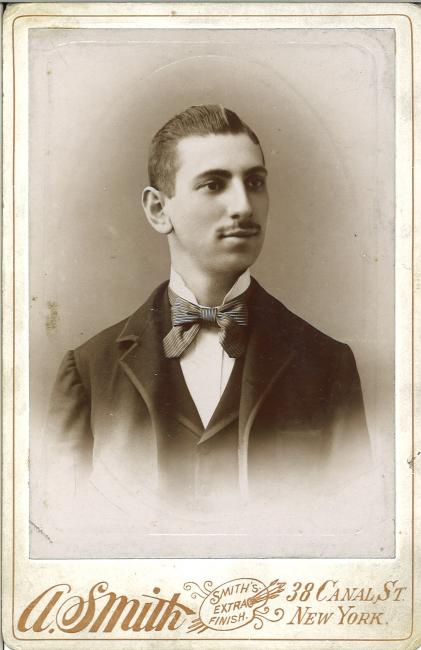

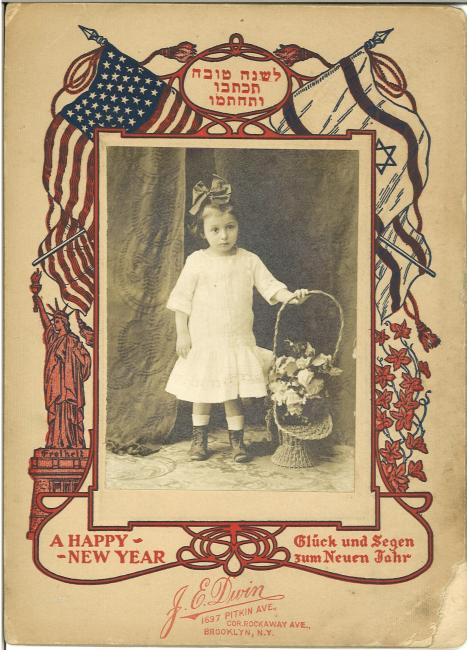

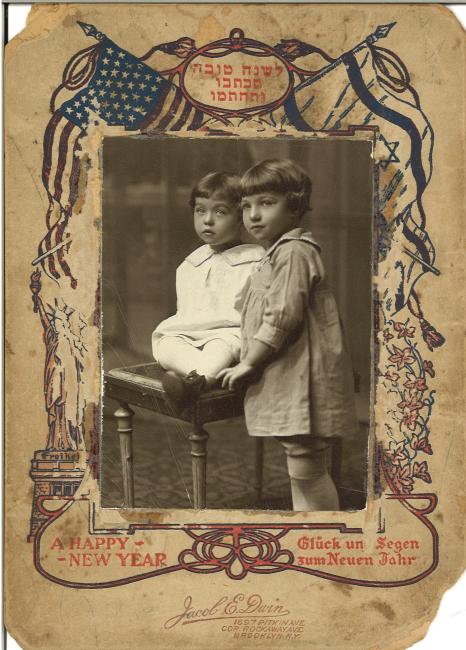

One of the threads running through this blog is the interplay of literature, music, and art in the Bronx salon of Yiddish poet Bertha Kling. This article introduces another element—photography—showing how it shaped the early life and work of Kling’s friend, writer and journalist Miriam Karpilove. Scholar Jessica Kirzane has championed Karpilove’s work, including in an earlier piece for this site. Here she shows us a youthful Karpilove navigating life in the big city while working in a milieu familiar to many young Jewish women—the photographic studio. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews were prominent in the burgeoning trade of portrait photography in major Russian cities like Odessa and Minsk, as well as in the immigrant neighborhoods of New York’s Lower East Side and Brooklyn. Karpilove’s account of this world is all the more fascinating for its insider perspective. A hartsikn dank—our warm thanks to Professor Kirzane for making her research into this little-known aspect of Karpilove’s biography available here for the first time.

—David Mazower

Photographs of widely published Yiddish author Miriam Karpilove display her keen artistic eye as a retoucher, her flair and her joy at the art of photography—with her flirtatious, defiant self as subject. What these flattering, glamorous portraits fail to convey at first blush is the backstory of the labor that produced them and Karpilove’s own role as a worker in this turn-of-the-century industry.

Miriam Karpilove (1888–1956) trained as a photographic retoucher while a teenager in Minsk before immigrating to America in 1905. Upon immigration, she lived in New York and Bridgeport, Connecticut, and worked in several different photography studios—from small shops catering to immigrants on the Lower East Side who needed photographs to send to relatives in Europe to large, factory-like studios producing publicity photos for celebrities of the stage. Though it is hard to track the details of Karpilove’s career, it seems that she worked in this industry for roughly a decade before her journalistic career was successful enough to leave this work behind.

Working in a photography studio wasn’t easy. It meant laboring all day, in the dark, with shuttered windows and no fresh air, in a narrow room on an upper floor of a poorly ventilated building. Dark curtains hung over the windowpanes. In one large studio that Karpilove describes, there were tables in a circle in the middle of the studio, each table with six stands in a row for six retouchers, and there was one small electric lamp in the middle for them to share, because “the boss understood how to be economical . . .”

The camera operator would take the subject’s portrait and then dip the glass in chemicals, dry it, and hand it to a retoucher. Using a sharp pencil, the retoucher would smooth out the imperfections on the subject’s face, getting rid of their freckles or wrinkles: “In a word, the photograph should look younger and prettier than the subject,” Karpilove explains. The retoucher would paint the photographs with India ink, adding details, such as the necklace a jealous woman spotted her next-door neighbor wearing, or removing the shadows that had fallen over someone’s face when the photograph was taken.

One customer complained, “I’m missing two fingers!”

“They’re not missing, they’re just bent.”

“Well paint them in, please. I won’t accept a picture without fingers.”

“One man with a ‘wild’ demeanor complained that we didn’t make him look ‘sweet,’ and he had to send the picture to his bride. He would pay to be beautified, otherwise what was the use? ‘A picture should look like a picture!’”

“We can’t make you look any better,” said the photographer.

“Never mind me! It’s the picture I want you to make look better!”

It was work that required a steady hand, an artistic eye, and technical training. Karpilove quips, “The most important artistic skill in photography is to suit the tastes of a tasteless public.”

In Russia such work was considered high status, Karpilove explains, for people whose parents did not want them to be low-class workers but didn’t have the means to send them away to be educated. Still, they were paid poorly for their “halfway-artistic art,” and when Karpilove was in Russia the retouchers organized themselves into a union. In America, photographs were cheaper and more widespread, photography workers were paid less, and the working conditions were poorer. “The workers looked more dead than alive” after spending so much time in the dark, poorly maintained room. “While making others look young, they made themselves old.”

“The floors were . . . soaked in oil, gasoline, and kerosene,” Karpilove recalls. “At any moment they could go up in flame . . . there was no elevator, no fire escape, and the stairs were made of thin boards that creaked under your feet.” When she thought about working in such a studio, she was quite hesitant: “I wasn’t in a hurry to work there. I stood there and wrestled with the question of whether I would put my life at risk there or die elsewhere of natural causes. But I figured I won’t live forever, one way or the other. . . . The dirt is indescribable. The darkness cloaks dust that has gathered over the many years. All the ‘improvements’ need to be improved. The Board of Health would find plenty to do here if it ever came to inspect.”

In the weeks leading up to Christmas the workers, from old men to young women of varying nationalities and languages, were forced to work overtime until two in the morning, and the hourly overtime rate was the same as the regular hourly wages. “They treated their workers like animals,” Karpilove concludes, though she recalls another worker remarking bitterly that at least it was “better than being in the trenches” of a World War I battlefield, “under a shower of bullets. There’s always someone worse off.” Stepping out onto Broadway after a day’s labor, Karpilove noted how awful it was to “see the lights and luxury for which we’re ruining our lives . . . it constrains your soul . . . it makes you feel small, weak, and lonely, like you want to go back into the darkness to escape all that you can see but can’t have.”

Karpilove was working as a retoucher in New York precisely at a moment of labor unrest among workers in this industry. In 1916, retouchers went on strike at the White Studio in New York, known for theatrical photography. Despite having no official union, the retouchers worked in concert to put aside their work for the sake of collective action to mitigate some of the worst abuses of the industry. Still, there were obstacles to such organizing in many studios. When Karpilove suggested unionizing in one studio, the retouchers told her: “We are intellectuals. How could we possibly organize? How can artists carry a union card that stamps the time you come and leave, like in a factory? Though we could burn just as easily as the workers at the Triangle factory, and work long hours and ruin our lungs and make ourselves blind . . .” The workers told her to avoid talking about a union because she was already getting a reputation as a troublemaker.

Karpilove makes clear that while the work was backbreaking and eye-spoiling for workers of all stripes, women in the industry faced particular challenges. When she was at work as a retoucherin or a retoucherke, a woman retoucher in a photography studio, Karpilove was often the only woman in the room.

It was dangerous and terrifying even to look for such work. Karpilove describes how as a woman living alone in New York she was frightened she would run into a threatening situation while job hunting and would become one of the missing women she sometimes read about. “The Yiddish newspapers didn’t have want ads for women retouchers, and I couldn’t read the English newspapers yet,” she recalls, “so I wandered the streets in search of photography studios . . . where I would go in and inquire about a position.” She recalls entering one shop that gave her such a disconcerting feeling that she considered looking for a policeman before going in.

“So you want to work?” asked the man in the studio. “Why do you want this low-class work? It pays very poorly.”

“Not working pays even less,” Karpilove quipped.

“If I were you, with your looks and your figure, I’d find something else to do . . .” he replied before offering her work at a low wage. He suggested she could try going to another studio but warned her that the man who ran it was a “lady chaser.” To test her skills, he asked her to retouch a photograph of a man and a woman in an immodest pose.

On another occasion, Karpilove describes the experience of going to work in a photography studio on 5th Avenue: “They led me into a dark room full of men, and I felt as though I had fallen into a foreign land. I had never been alone with so many men before. They looked at me curiously with stolen glances and one called out, ‘We have ourselves a girl!’”

Some of the workers were incredulous, asking “Why do we need lady retouchers? Aren’t there enough male ones toiling?” or suggesting, “You’d be better off getting married and taking yourself out of the marketplace!” while others are happy to have her around because then the men “might stop with their ugly speech. They will restrain themselves in front of a lady.”

But they weren’t so restrained. They made jokes and sexual innuendos and gave her a hard time for not laughing. They insulted her “not only with their tongues, but with their hands and feet.” One worker placed his leg closely against hers no matter how often she scooted away or asked him to stop, to the amusement of the rest of the workers. Describing her anger, she writes, “My pencil broke on the negative because my fist was so tightly clenched.” Standing up, Karpilove lifted her chair and threatened, “Say another word and I’ll break this chair over your head!”

Karpilove’s writing about photography work displays the same sense of vulnerability, and the same resilience and defiance, that readers came to expect from her writing about romance or about the world of journalism. If a picture tells a thousand words, there’s yet a thousand more words behind each picture, stories of the labor and the working conditions that produced the images of the Yiddish writers we know and love.

Jessica Kirzane is the assistant instructional professor of Yiddish at the University of Chicago and the editor-in-chief of In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies. She is the translator of three works by Miriam Karpilove: Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle Against Free Love (Syracuse UP, 2020), Judith (Farlag, 2022), and A Provincial Newspaper and Other Stories (Syracuse UP, forthcoming).

Sources:

Miriam Karpilove, “Fotografishe bilder” (Photographic Images), Der Tog (The Day), Nov. 11, 1914, p. 8

Miriam Karpilove, “Zey makhn andere sheyn un yung un zikh alt” (They Make Others Young and Pretty and Themselves Old), Forverts (Forward), May 6, 1914, p. 4

Miriam Karpilove, “In der finster” (In the Darkness), Di Naye Tsayt (The New Time), Aug. 14, 1914, p. 5

Miriam Karpilove, “Aruntergenumen,” (Taken Away), Di Naye Tsayt (The New Time), May 8, 1914, p. 5

Miriam Karpilove, “Lebedig begrobene” (Living Corpses), The Ladies Garment Worker, May 1916, pp. 27–29

“Retusshoren fun Vhayt’s studio aroys in strayk” (Retouchers from White’s Studio Out on Strike), Der Tog (The Day), March 3, 1916

Acknowledgements:

Photographs of Miriam Karpilove courtesy of David Karpilow, Lindsay Flanagan, and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. All other photographs courtesy of the David Mazower Collection.

With thanks for Sabina Bruckner for her research assistance, and to 2022–23 Yiddish Book Center fellows, Charlotte Apter, Joseph Reisberg, and Caleb Sher for their help editing and formatting.