Miriam Karpilove’s FOMO

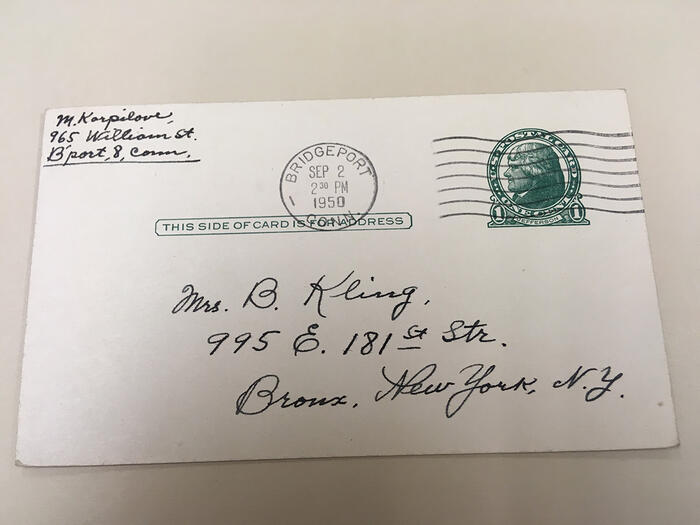

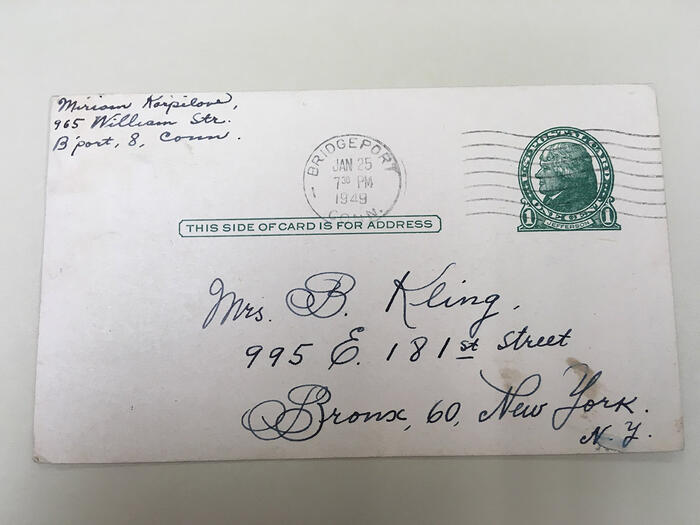

As our first guest contribution to this blog, we are delighted to feature this post by scholar and translator Jessica Kirzane. We reached out to Jessica in connection with two remarkable postcards in the Bertha Kling archive at the YIVO Institute. Mailed by the Yiddish writer Miriam Karpilove to Kling, and written in neat, tightly-packed lines, the cards offer an intimate window into the friendship between the two women. Just like Kling, Karpilove came to the US as a teenage immigrant from Russia. Born in Minsk in 1888, she emigrated in 1905, becoming a respected author of popular fiction and one of the first women to make a living as a staff writer for the American Yiddish press. We are grateful to Jessica Kirzane for translating these postcards and providing an introduction to this late-developing friendship.

In 1949, Miriam Karpilove, widely published author of serialized novels, stories, and sketches, was living with her brother Joseph “Nuck” Karpilow in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Having spent much of her adult life among bohemian Yiddish circles in New York City, when Karpilove left for Bridgeport to come to her newly widowed brother’s aid it appears from her letters that she felt desperately lonely, cut off from the gossip and productivity of the world that she had once so relished being a part of.

One of her great regrets was in missing out on the gatherings at Bertha Kling’s home. In a postcard dated January 24, 1949, Karpilove praises Kling’s gatherings of Yiddish women writers, asserting, “I think it’s long overdue that women writers should have a chance to hear each other. The power has been in the hands of male writers for too long.” Karpilove imagines herself into the scene, insisting that if only she lived in New York instead of Bridgeport, she wouldn’t miss a single meeting.

But Karpilove was, after all, stuck in Bridgeport, despite her hopes that she would be able to find an apartment for herself and her brother and return to the New York she loved. Instead, she kept up a correspondence with Yiddish writers and awaited their letters anxiously, even tempestuously. On receiving Kling’s postcard, Karpilove scolds her for having taken so long that “I had almost given up on receiving a letter from you” and passive aggressively concedes that “the warm tone” of Kling’s letter “makes up for its brevity.” In this and a later postcard dated September 1, 1950, she recognizes how busy Kling must be with her door ever open to artists and writers, but even that recognition comes tinged with regret that Kling, who claims to have such affection for Karpilove, did not write frequently enough to satisfy the attention-starved writer.

These two postcards demonstrate the centrality of written networks between writers but also the way these networks were superseded by the in-person relationships that Karpilove so deeply lacks. It’s clear from the letters that Karpilove has met Kling in person before—she writes that she admires Kling’s sweet singing voice, for instance—but it appears that the two did not have a chance to get to know each other well before Karpilove left for Bridgeport, and writing to one another cannot satisfy Karpilove’s desire to be recognized, needed, and loved by Kling or to be at the center of the social world of bohemian Yiddish writers.

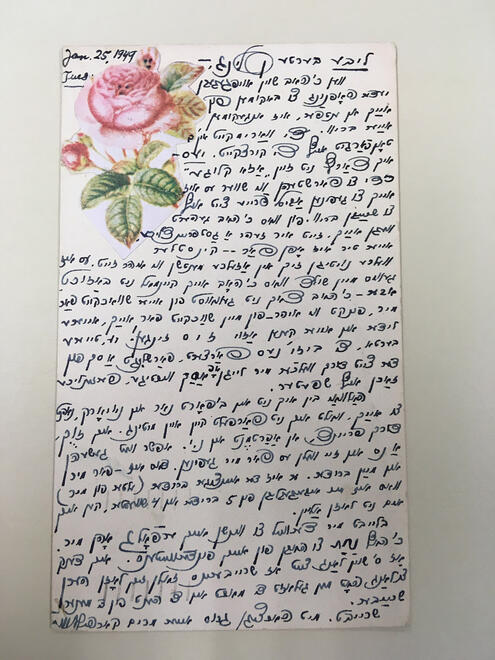

Miriam Karpilove to Bertha Kling, January 24, 1949

Dear Bertha Kling—

Just when I had given up all hope of receiving an answer from you, I received your letter. The warmth of your tone makes up for its brevity. Yes—I need not be "so clever" in order to understand how hard it must be for you to find free time in which to write letters. From what I hear about you, you are very hospitable—your door is always open for . . . artists who are in need of people like you. It's certainly my own fault that I never came to visit you, but I didn't know about your weakness (shvakhkayt) for me just as you didn't know about my weakness for you, your poetry and your sweet singing voice! Yes, my dear Bertha, business demands swallow up so much time and we put off for later the important, personal matters.

If only I wasn't in Bridgeport but in New York, near you, I wouldn't miss a single meeting. With the help of friends I'm looking for an apartment in New York, and maybe a miracle will happen and they'll find one. That is—one for me and my brother. He is the only brother (older than me) from among my 5 brothers and 4 sisters, who is devoted to me. I can't leave him alone.

In the meantime, I wish you success without me. I hope to be proud of you from afar. (Kh’hof nakhes tsu hobn fun aykh fundervaytens). I think it's long overdue that women writers should be heard. For too long we've left the power in the hands of male writers. (Tsu lang hot men gelozt di makht in di hent fun di mener shrayber).

Write to me. With warm greetings, your Miriam Karpilove

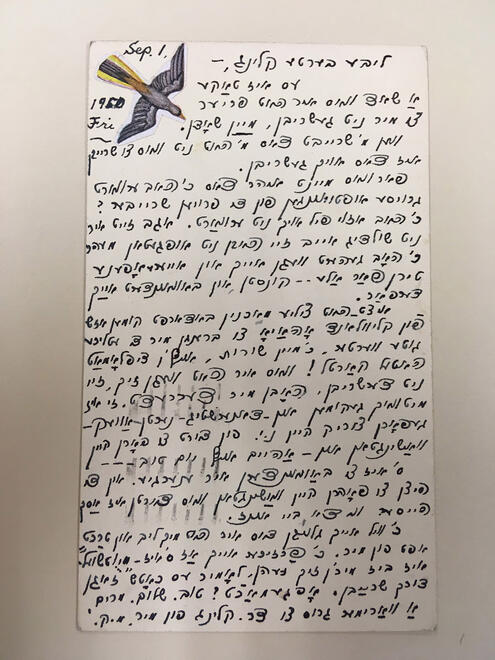

Miriam Karpilove to Bertha Kling, September 1, 1950

Dear Bertha Kling—

It really is a shame that you did not write to me sooner, my darling.

When you write that you don't have anything to write, that's writing too.

Why did you think that I was expecting great accomplishments (groyse oyftuungen) from the women writers? I wasn't expecting that much. Anyway, it's not your fault that they didn't accomplish more than they did. I've heard about you and about how your door is open to all sorts of . . . art, and I've been astonished by it.

Just now, Celia Makhnin [?] came here from Cleveland, Ohio and brought me some good words. I mean lines of poetry—on Diplomat Hotel stationary!—that you didn't tell me about yourself when you wrote. We discussed them. She arrived on Wednesday and left on Thursday night to go back to New York and from there to go to Washington and then to return home for the holiday.

I marvel at her energy, to travel in this heat to Washington, which is even hotter than it is here where I am.

I want to believe that you love me and think of me. I assure you that it's mutual and until we see each other again let's at least say so in writing. Deal? Good. Yours, Miriam

Warm regards to Dr. Kling from me, M. K.

Jessica Kirzane, a three-time alumna of the Yiddish Book Center, is assistant instructional professor of Yiddish in the department of Germanic studies at the University of Chicago. She is also the editor-in-chief of In geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies, and the translator of Miriam Karpilove's Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle against Free Love (Syracuse University Press, 2020). A full list of her translations (including more work by Karpilove) and academic publications can be found at jessicakirzane.com.

We would like to thank the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and its director of archives, Stefanie Halpern, for permission to reproduce the two postcards.