Revealed After 100 Years: Abel Pann’s Showpiece Portrait

"I've been clearing out my closet and found a picture of my grandfather"

When we embarked on this project, it was impossible to foresee how far the circle extended and the unexpected connections we would find.

One of the joys of a project like Bronx Bohemians is the unexpected find—a family photograph or heirloom that throws new light on this home-based salon. From the beginning, we were attracted by the diversity of the circle that formed around the Yiddish poet Bertha Kling in the early twentieth century. It was clear that an astonishing cast of Jewish writers and creative artists had stepped over the Klings’ threshold and found a community of kindred spirits. But when we embarked on this project, it was impossible to foresee how far the circle extended and the unexpected connections we would find—for example, the story of the Klings, the Sholem Aleichem family, and the painter Abel Pann.

Like so much else about this blog, this began with an email from Bertha Kling’s granddaughter, Deborah Ramsden:

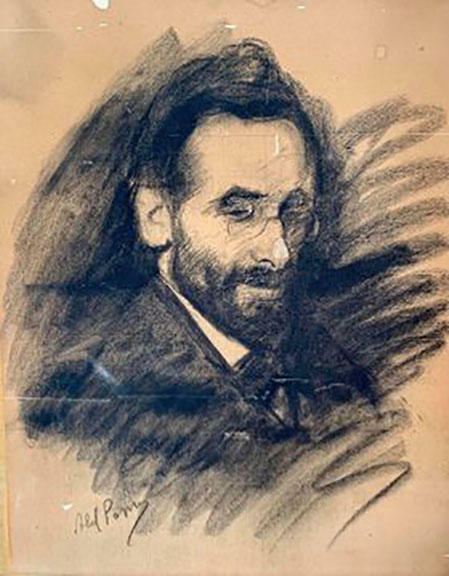

“I’ve been clearing out my closet,“ she wrote me, “and I found a picture of my grandfather. It’s fragile, but I took the best photo I could. Maybe you can make out the signature.”

Attached was a sketch of Bertha’s husband, Dr. Yekhiel Kling:

Immediately recognizable with his trim beard and half smile, Dr. Kling looks very much as he appears in the circa 1920 group photograph of the Bronx bohemians that we featured in an earlier post. Beautifully executed, with a flourish of broad stokes framing the face, the portrait has the casual intimacy of a street artist’s sketch. But a glance at the signature confirmed this artist was anything but an amateur.

“Deborah!” I fired back. “Your sketch is by Abel Pann!!!”

Pann is one of the great names of modern Jewish art, even if his reputation has waned in recent decades. Like Hermann Struck and Josef Budko, he was part of a pioneer generation of celebrated European Jewish artists who brought Western methods of academic painting to mandate-era Palestine. All have seen their reputations eclipsed as narrative painting has gone out of fashion but arguably none more than Pann.

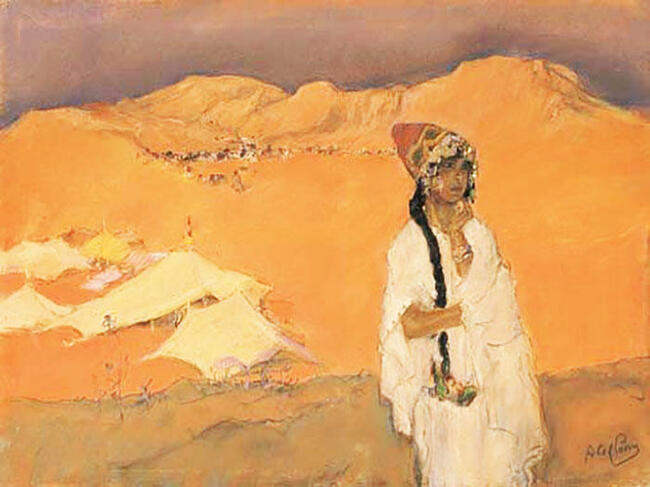

Pann departed from the Western Christian tradition and used darker-skinned Yemeni Jews or Bedouins as models, giving his Biblical world a distinctly Eastern cast.

Today Abel Pann is best known, and most valued by the art market, as a painter of richly colored scenes from the Bible. A pageant of extravagantly-bearded patriarchs, bejewelled women, swirling robes, and fiery desert skies—think Cecil B. DeMille crossed with Diaghilev's Ballets Russes—these images can easily strike the contemporary viewer as overblown and melodramatic. Nonetheless, at his best, Pann was brilliantly accomplished and quietly revolutionary. Just as Itzik Manger peopled his Yiddish retelling of Bible stories with earthy characters from the shtetl, Pann departed from the Western Christian tradition and used darker-skinned Yemeni Jews or Bedouins as models, giving his Biblical world a distinctly Eastern cast.

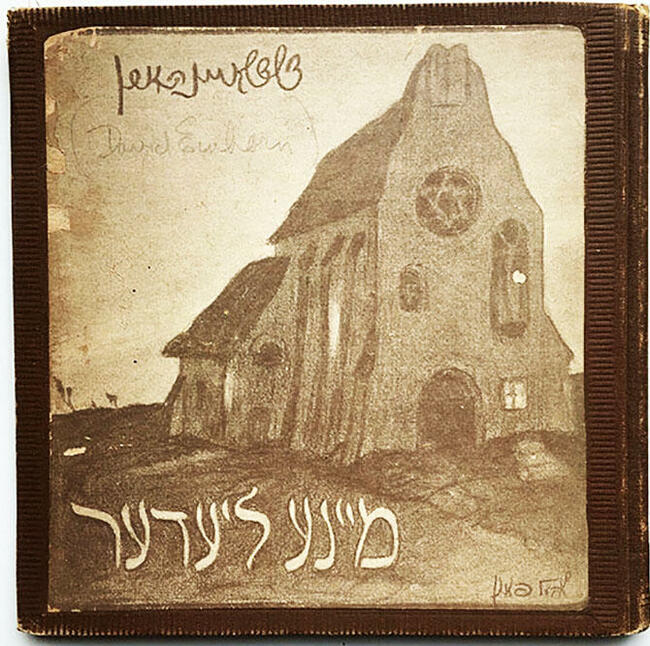

But it’s as a European artist that Pann is truly forgotten. He was born Aba Pfefferman, the son of a rabbi, in Kreslava, Latvia, in 1883. A promising teenager, Pann studied art in Vitebsk with Marc Chagall’s teacher, Yehuda Pen, then furthered his studies in printmaking and painting in Vilna and Odessa. In 1903 he visited Kishinev, documenting the pogrom in a series of drawings. That year, he settled in Paris, and, for over a decade, produced an enormous body of work, including portrait sketches, caricatures, and illustrations for commercial magazines. Pann also had connections to the Yiddish literary world. Around 1912 he provided a cover illustration for a slim volume of poems by the up and coming writer Dovid Eynhorn:

Eynhorn’s small, square-shaped book, Mayne lider (My Poems) included many poems on messianic and Jewish nationalist themes—a natural fit for Pann, a committed Zionist whose work was increasingly preoccupied with the modern Jewish fate. In 1913, Pann visited Jerusalem and agreed to teach painting at the Bezalel School of Art.

The unprecedented destruction of frontline Jewish towns and villages in WWI became an obsession worked out in his art.

Returning to Paris to pack up his belongings, he was trapped by World War I and spent the next few years in the city. According to the scholar Aviel Roshwald, Pann came to see Eastern Europe “as nothing but a physical and spiritual graveyard for Jews.” The unprecedented destruction of frontline Jewish towns and villages in WWI became an obsession worked out in his art. Roshwald writes:

“In 1916 he produced a series of harrowing images of the persecutions, hoping to draw public attention in the West to the plight of Russia’s Jews. Many of the etchings bore ironic captions: “The Traitors” depicted a group of Jews hanging from the gallows as alleged spies; “Hiding from their Protectors” showed a group of terrified Jewish women and children seeking cover in a forest while Russian troops marched by; “The Son’s Return” portrayed a young man arriving home to find his father lying in bed with a bullet hole in his head. Most disturbing of all to the eye of a post-Holocaust observer is the print entitled simply “Cattle Cars,” which shows emaciated refugees stuffed into cattle cars, hands and arms bent at sharp angles as they reach out in desperation, while a soldier with a bayonet at his side stolidly stands guard, his back turned to the supplicants.”

The drawings enraged Russia, France’s ally in the war. According to Pann, the Russians lobbied successfully to ban a wartime exhibition of the drawings in France. Stung by the experience, Pann left France in 1917 and came to America, staying for three years until his permanent move to Jerusalem in 1920.

Pann enjoyed considerable success in the US, notably with a large exhibition of his work at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1920. Not much has been written about his time in America, but the portrait sketch of Dr. Kling is not the only evidence of his involvement with the Klings’ circle.

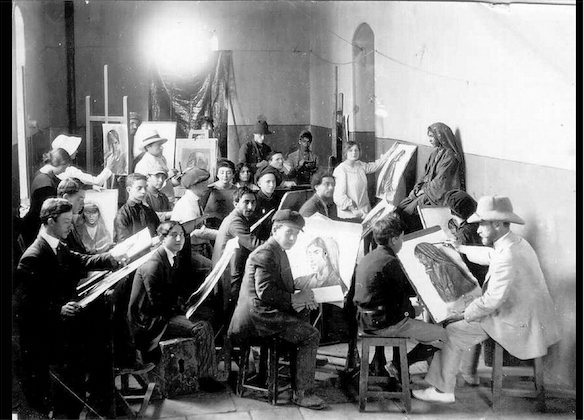

An undated photograph in the Bertha Kling archive at the YIVO Institute shows Abel Pann (bottom right) relaxing in the company of the Sholem Aleichem family, probably at their home in the Bronx. Five relatives are named on the back of the photo: Sholem Aleichem’s widow, Olga, is on the far left, perhaps holding one of her husband’s books (he died in May, 1916); her daughter, identified as 'Marusia Goldberg’ (i.e., Marie Waife-Goldberg) is bottom left; and next to Pann is another daughter, ‘Tisia’ (Tissa), her husband, the Yiddish and Hebrew writer I. D. Berkowitz, and their daughter Tamara.

Bertha Kling, an amateur singer, sang in her passionate manner the same romantic folk songs that my father always enjoyed, but somehow they sounded hollow.

The photo is also a reminder of the close ties between the Sholem Aleichem family and the Klings. We know from the memoir by Dr. Kling’s nephew, Berl Boym, that Sholem Aleichem was an occasional guest at the Klings’ home salon in the early years. Another eyewitness, Sholem Aleichem’s daughter, Marie Waife-Goldberg, recalled the last time close friends saw the ailing writer alive at the family home at 968 Kelly Street in the Bronx. The date was April 29, 1916, the occasion a party for his daughter’s Tissa’s birthday:

That evening was not unlike the others. Bertha Kling, an amateur singer, sang in her passionate manner the same romantic folk songs that my father always enjoyed, but somehow they sounded hollow. The famous Yiddish dramatist Peretz Hirshbein told an amusing story in his inimitable, if elaborate, style, as he did on other evenings, but it did not call forth the usual levity.

Early on Saturday morning, May 13, 1916, the world’s most famous Jewish author died. For forty-eight hours, his body lay in state in the apartment as an honor guard of Jewish writers kept watch and a continuous line of mourners passed by the bier. The funeral brought up to 200,000 mourners onto the city’s streets, many of them weeping bitterly as though they had lost a loved one.

The bond between Bertha Kling and the Sholem Aleichem family was evidently deep and long-lasting. A later photo in the Kling archive at YIVO shows Bertha with Tissa Berkowitz, their heads touching, a picture of enduring, intimate friendship.

As for Pann, he returned to Jerusalem in 1920 to take up his long-delayed appointment at the Bezalel School of Arts. He remained there until his death in 1963, traveling abroad at regular intervals to promote his acclaimed series of lithographs of the Bible.

His sketch of Dr. Kling, unseen for a century and now rediscovered, is a missing part of the Abel Pann story—a memento of the Bronx circles Pann moved in during his first trip to the US. It’s also another indication of the significance of the Klings’ salon—a haven of hospitality in a strange city but also a site of cultural exchange for some of the major Jewish artists of the early twentieth century.

Notes:

Special thanks to Deborah Ramsden for sharing the portrait of her grandfather with us. Thanks also to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and its director of archives, Stefanie Halpern, for permission to reproduce photos from the Bertha Kling Collection.

The quote by Aviel Roshwald is from the book European Culture in the Great War: The Arts, Entertainment, and Propaganda, 1914–1918 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), co-edited by Aviel Roshwald and Richard Stites.

Marie Waife-Goldberg’s memoir, My Father, Sholem Aleichem, was first published by Simon and Schuster, New York, in 1968.