My Life as a Radical Jewish Woman: Reading Resources

As an historian reading [Puah Rakovsky’s] memoirs, I puzzled over the question of historical significance. Puah Rakovsky was well known in her own time as an educator with a fine command of Hebrew, a Zionist, and a feminist activist. She translated thirteen books into Yiddish from German, French, and Russian, published articles and pamphlets, and commented upon the writing of others. Writing of Rakovsky's popularity and stature in 1920s Warsaw, Esther Rosenthal-Schneiderman noted that legends had sprung up about her even in her youth, "like a real heroine." Her eightieth birthday in 1945 was mentioned in the press in Palestine, and when she died in May 1955 she was honored with a front-page obituary and a photograph in Davar, the daily newspaper of the Labor Party. After her death, no less a figure than the Yiddish author Jacob Glatstein wrote a combined review essay and obituary that hailed her as one of the first Jewish women's rights activists on the world scene.

Puah Rakovsky certainly had an impact on her own time, and it was recognized by her contemporaries. Yet she has been forgotten, I would argue, because women's activity in general and their political and feminist activism in particular did not matter to historians. Since history is the remembered past, historians have the power to determine what we remember of periods that we did not personally experience and to overlook the rest, essentially erasing it from our collective memory. As feminist historians have argued and demonstrated for a generation, that erasure has produced a flawed understanding of the past. Recognizing this, historians now have both the opportunity and the obligation to construct a collective memory that includes women's experience.

—Paula Hyman, "Discovering Puah Rakovsky"

The section excerpted from Paula Hyman's journal article "Discovering Puah Rakovsky" above reveals the irony of Puah Rakovsky's status as a forgotten historical figure; a woman so dedicated to women's rights is forgotten in our collective memory, erased as history continues to disregard the contributions of women.

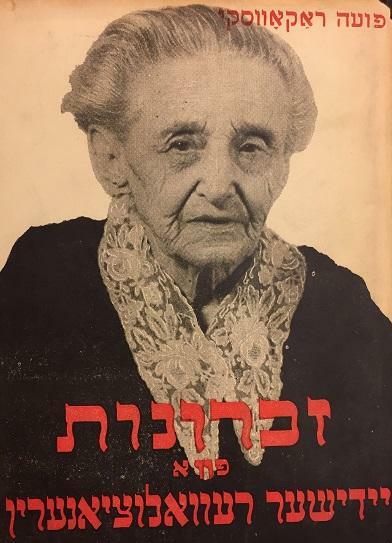

As the Great Jewish Books Book Club dives into Puah Rakovsky's memoir, My Life as a Radical Jewish Woman (originally, in Yiddish, Zikhroynes fun a yidisher revolutsionerin), the following resources may facilitate for readers an exploration of the places, institutions, and languages that shaped Rakovsky's world, as we work together to recover Rakovsky's place in history.

Background: Puah Rakovsky

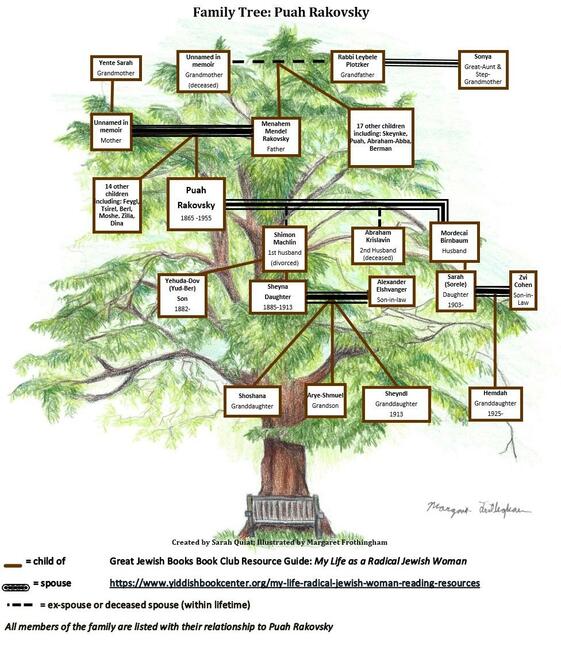

As described by Paula Hyman in an illuminating article for the Jewish Women’s Archive, Rakovsky was born in Bialystok on July 3, 1865, the first child of fifteen in a traditional family with a long rabbinic lineage. In the memoir, we follow her story from here, as she creates a woven map connecting Bialystok to many corners of the Yiddish-speaking world. She guides us through phases of her life, concluding her book with the year 1935 in Palestine, though she continued to live there until her death in 1955. Take some time to peruse the article, or to consult with it regarding confusing passages.

Bialystok: Puah Rakovsky's Hometown

After leaving Bialystok, the city where she spent her childhood and adolescence, Rakovsky longed to return. We may question: what was it that made Bialystok so precious to her? While her family’s presence and memories there are likely reasons, the YIVO Encyclopedia’s article on the city may provide additional explanations as to its significance for Rakovsky. As historian Rebecca Kobrin explains in the article, the combined periods of economic downturn and horrible factory labor conditions produced a unique and dramatic stage for revolutionary Jewish labor movements and political parties (in which Rakovsky involved herself throughout her life). Białystok served as a center for the Bund, Ḥibat Tsiyon, and Esperanto movements at various moments in the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition to the article above, there is an excellent study of Jewish Bialystok available in Kobrin’s book, Jewish Bialystok and Its Diaspora.

Warsaw

Warsaw held an important place in Puah Rakovsky’s life; it was in Warsaw that she taught and directed a celebrated Jewish school for young women, the Yehudia kheyder, and where she first actively engaged in Zionist activity. It is also where she became one of the founders of the Jewish Women’s Association, Di yidishe froyen asosiatsiye (the YFA). Anthony Polonsky’s article on Warsaw for the YIVO Encyclopedia provides additional insights into Rakovsky’s relationship with the city. Polonsky lays out the demographics of the city in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and notes that the community was largely Yiddish-speaking during the periods of Rakovsky’s residence in Warsaw (83.7% in 1897). He adds that the movement of Jews from the Russian Pale of Settlement to Warsaw became legal after 1868 and grew after the Russian Empire’s introduction of the 1881 anti-Jewish laws, which did not apply in Congress Poland; the new laws resulted in notably increased emigration from the Pale (and cities like Bialystok) to Warsaw. According to Polonsky, by the beginning of the World War I, approximately 150,000 Litvaks like Rakovsky had immigrated from the Russian Empire, importantly shifting the dynamic of historically Hasidic Warsaw.

Gender and Institutions

While living in Warsaw, Puah Rakovsky wrote and published a pamphlet in 1918 entitled Di yidishe froy (“The Jewish Women”), where she called for the creation of a national Jewish women’s organization, appealed to women to engage in Zionist work, and argued that Jewish women must fight for women’s suffrage in Jewish communal elections. Di yidishe froyen asosiatsiye (the YFA) was established in Poland after World War I. The YFA joined WIZO, the Women’s Organization of the Zionist movement, immediately after the latter’s founding in 1920 and served as its Polish branch. As Hyman explains in an article about the YFA for the Jewish Women’s Archive (JWA), the organization was founded by Rokhl Stein, Leah Proshansky, and our memoirist, Puah Rakovsky. Hyman describes the YFA as “a women-led, explicitly feminist organization.” She also describes it as different from the Bundist Yidisher arbeter froy (the YAF, “Jewish Working Women”) established in 1925 (by men rather than women, Rakovsky notes in her memoir) because working-class women largely organized the YAF and members affiliated with the Bund, whereas “the YFA was middle-class in its membership, independent of all political parties though not apolitical, and Zionist in its orientation.”

While contextualizing Rakovsky’s involvement in various Zionist women’s organizations and movements during the interwar period, it is important to acknowledge the larger political and social situation for women at that time in Poland. Gershon Bacon notes in an article for the JWA that Jewish women living in interwar Poland frequently found themselves restricted to the home rather than the marketplace upon attainment of middle-class status. He also highlights that the Jewish women of Poland were pushing for women’s suffrage and for a voice within political organizations (including Zionist organizations) and in kehillah elections, the internal and local Jewish communal elections. He also notes, however, that these movements (in which Rakovsky was involved) found few supporters among other Jewish women. Bacon suggests that many women did not participate in women’s rights organizing work because they believed they must prioritize broader issues for the Jewish community: “the leaders of the time identified other issues, such as securing political rights or economic security, or solving the ‘Jewish problem’ through Zionism, socialism or emigration, as deserving of immediate attention.”

Yiddish and Puah Rakovsky

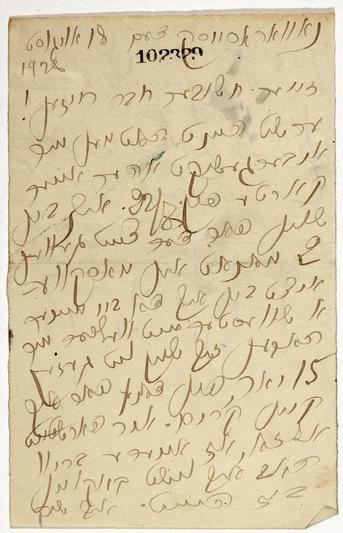

The YIVO Digital Archive offers a remarkable letter that Puah Rakovsky sent to Zalman Reisen in Vilna while she was visiting Novorossiysk, USSR, in 1928. In the letter, she includes a short autobiography for his Leksikon fun der yidisher literatur, prese un filologye (“Lexicon of Yiddish Literature, Press and Philology”). For those who read Yiddish, deciphering her words and contextualizing them within the final chapters of her memoir—with her visit to her son in the USSR in the late 1920s—is a fascinating endeavor. For non-Yiddish readers, it may be interesting to look at her handwriting and to piece together the patterns and visual attributes.

Rakovsky was unique in her commitment to both Yiddish and Hebrew as vital languages within the Zionist movement. In this excerpt from the Center’s Wexler Oral History Project, scholar Katarzyna Czerwonogóra points to Puah Rakovsky’s championing of Yiddish as a language that was as key as Hebrew to an envisioned united Jewish nation, and contrasts Rakovsky’s vision with the larger Zionist movement’s attitude towards Yiddish.

We hope that these materials provide valuable context for Puah Rakovsky’s memoir. She shared with us her world of Yiddish and Hebrew, of Zionism and Diasporism, of exile and return, of tradition and of modernism. Her memoir is consuming and is, indeed, revolutionary. Hob hanoe, enjoy!

—Sarah Quiat