Burning Lights: Reading Resources

Some critics saw something miraculous in the fact that an “assimilated” Jewish woman, who had written about the “liberation of the Russian peasant” and had frequented the exalted cultural milieux of the West, should all of a sudden sit down to write in Yiddish about Sabbath and the holidays in the old country. Some romantic people may even see in this the finger of God and another proof of the eternity of Israel. But theirs would certainly not be a literary point of view.

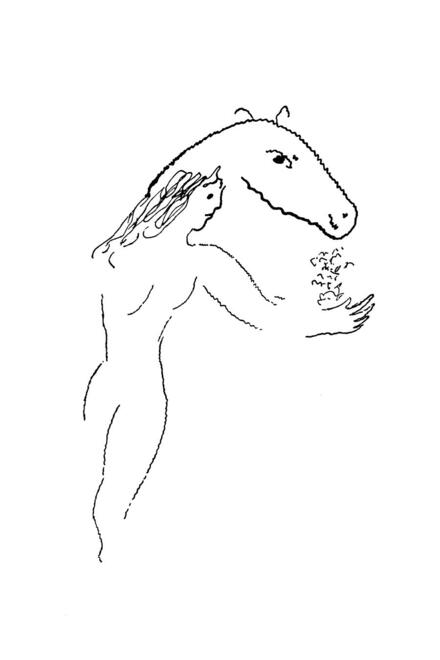

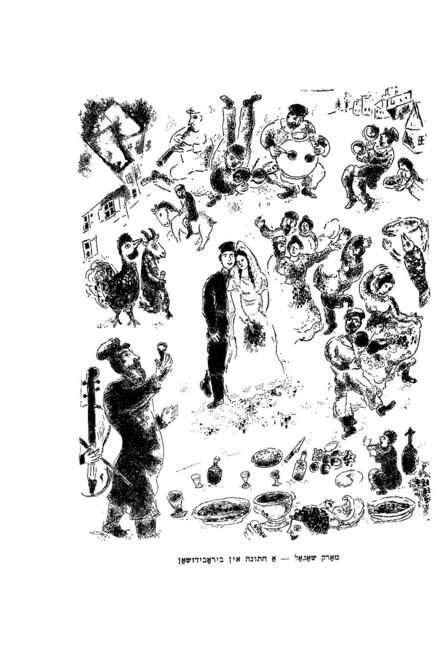

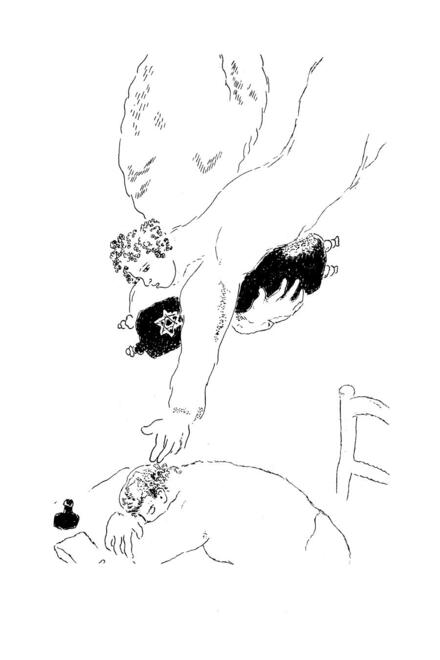

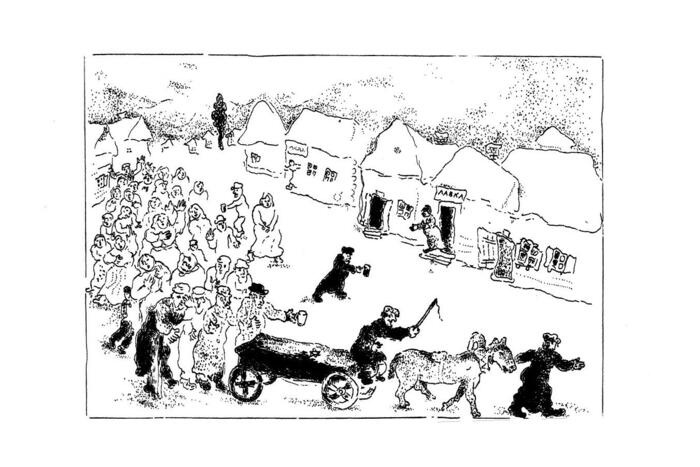

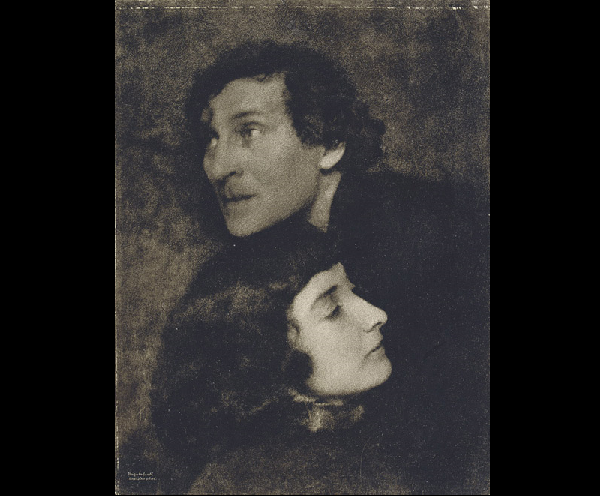

Reading the book, one is impressed by its all-pervading anguish and its nostalgia for the old world—emotions that do not get lost in the English translation. The descriptions are picturesque. Streets and houses, animals and inanimate objects, take on soul and personality. This old world is seen not only through the eyes of little Bashke, but also through those of the wife of a great painter. Marc Chagall’s drawings, which accompany the text, evoke the spirit of the epoch in a few strokes.

—J. Ayalti, review of Burning Lights, Commentary, December 1946.

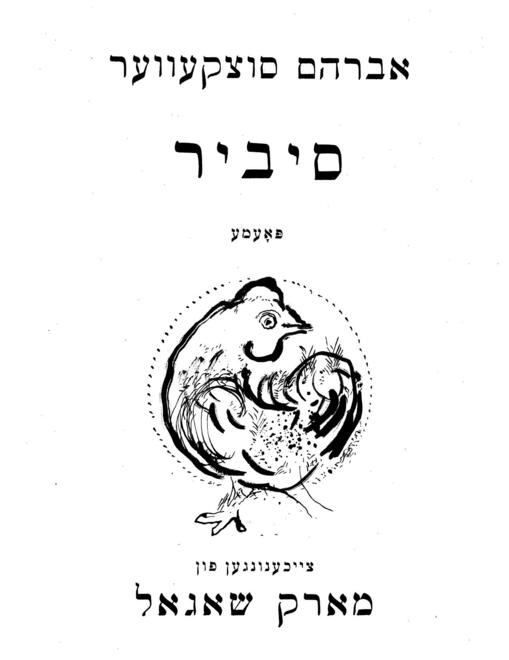

Together, we will discover the Chagalls’ “double portrait”: Burning Lights, translated from the Yiddish original Brenendike likht by Norbert Guterman in 1946. Though she submitted her Yiddish memoirs to a publishing house—the Book League of the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order—Bella Chagall did not live to see their publication. They were edited and published posthumously in two volumes by Marc Chagall after her sudden death from an infection in 1944.

Through Burning Lights, Bella Chagall takes us into the world of Chasidic Jewry in Vitebsk during the earliest years of the nineteenth century. She accomplishes this task through the sometimes surreal and enchanting observations and experiences of her childhood self, Basha—nicknamed Bashke, or Bashinke—though she wrote the memoir in her forties. Through stories of her childhood, she engages with freedom and restriction, happiness and sorrow. Before France, before Nazism, before Marc Chagall, we read about Basha and her adventures through the world of Russian Jewry.

We hope this guide can act as an interlocutor, facilitating conversations between you and the text. We hope that you will engage with this survey of relevant information about Bella and Marc Chagall’s lives and discover the lasting impact of the Chagalls’ extraordinary love story.

Background on Vitebsk, Belarus:

Key to Burning Lights is Bella Chagall’s childhood town, Vitebsk (Vitsyebsk). Though now a city in modern-day Belarus, she grew up under the tsarist Russian Empire. As Arkadi Zeltser’s article in the YIVO Encyclopedia page on Vitsyebsk explains, the formative figure Rabbi Menahem Mendel lived in the city, developing Vitebsk into an important center of Lubavitch Chasidism. In the late nineteenth century, Jews made up more than half of the population of Vitebsk.

Marc Chagall and many others studied at Yehudah Pen’s art school in Vitebsk, which opened in 1897. In the YIVO encyclopedia article on Chagall, author Benjamin Harshav explains that he went on to found a new art institute in 1918, the People’s Art School, after he was appointed as “Plenipotentiary on Matters of Art in Vitebsk Province” by the Bolshevik Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatolii Lunacharsky. Under Chagall, a Jewish department was opened at the local museum in 1919, and a Yiddish theater and newspapers appeared (though these new cultural venues and forums only lasted until 1923). Chagall left for Moscow and then Berlin, finally leaving for Paris in 1922.

Although the Jewish population fell to about 2 percent in the decades after World War II, the Obshchestvo Liubitelei Evreiskoi Kul’tury (Society of Friends of Jewish Culture) was founded in 1989 to preserve Vitebsk Jewish cultural history, according to Zeltser. The Marc Chagall Museum opened in Vitebsk in 1992.

Background on Bella Chagall:

A beautifully written and unusual memoir, Bella Chagall’s Burning Lights paints a vivid and dreamy picture of a young child’s experiences through the Jewish holiday cycle. We learn about her childhood, about the family she was born into as Basha Rosenfeld (the youngest of seven, in 1895), and about her parents Shmuel Noah Rosenfeld (Shmul Noah) and Alta (née Levant).

We do not, however, receive a thorough biography of Bella Chagall’s entire life. A short biography prefacing Burning Lights surveys her impressive education, from the secular Vitebsk Gymnasium to her matriculation in 1912 as a student in the Faculty of Letters at the University of Moscow. From there, we learn of Marc Chagall and Bella Chagall’s marriage on July 25, 1915, and their move to Paris in 1922, where Bella Chagall translated and edited Marc Chagall’s biography, My Life, from Russian into French. These details complicate our understanding of the woman known largely as Chagall’s muse; we begin to appreciate her as Bashke, a child from a traditional Chasidic family who grew into Basha and Berta and Bella, a college-educated translator and author, balancing multiple languages, worlds, and her husband’s career.

Some readers may desire a more comprehensive biography of her life before or after these childhood recollections. She authored an additional short memoiristic fragment, tracing her adolescence through her first encounter with the artist whom she would marry, published as First Encounter. Written similarly to Burning Lights, it weaves a narrative, painting memories through rich and visceral descriptions rather than through listed facts. David Mazower, the Yiddish Book Center’s bibliographer and editorial director, wrote a wonderful article for our website about the very special copy of Di ershte bagegenish (First Encounter) in our collection, available in our digital library and as an audiobook in the Sami Rohr Library of Recorded Yiddish Books.

Other than First Encounter, the best sources of information about Bella Chagall are the biographical works about her husband, Marc Chagall. A particularly useful text is Marc Chagall and His Times: A Documentary Narrative by Benjamin Harshav with translation by Barbara Harshav (whose name will be familiar to longtime members of the Book Club), which includes letters from and about Bella Chagall, photographs of her and her family, information about the publication of Burning Lights and First Encounter, and many more relevant details.

Bella Chagall is remembered largely through descriptions of Marc Chagall’s love for her. He continued to paint her, write poetry about and for her, and love her until his own death in 1985. Burning Lights, while organized and edited by Marc Chagall, is one of two narratives about Bella Chagall crafted and told by her.

Bella and Marc Chagall's Relationship:

Moyshe Shagal was born in Vitebsk (or possibly Liozna, a town within the Vitebsk region of modern-day Belarus) on July 7, 1887. He was the first of eight children born into an observant Jewish family. Bella and Marc Chagall both grew up in Vitebsk and met for the first time in 1909. According to their official birth dates, Marc Chagall would have been twenty-two and Bella Chagall would have been fourteen. In Marc Chagall and His Times, however, author Benjamin Harshav speculates that she must have been older; among other details, she supposedly finished gymnasium with her classmate, Thea Brachman, in 1907, which means that she was likely eighteen or nineteen at the time and, therefore, probably twenty or so when she and Chagall met.

They each wrote about their first meeting at Thea Brachman’s home (at the time, a romantic partner and model for Marc Chagall’s painting and a friend of Bella Chagall’s). “The First Meeting,” an article in Narrative Magazine, places their narratives in conversation with each other.

Marc Chagall left for Paris but returned to Vitebsk in 1914, reuniting with Berta Rosenfeld (who was still called Basha by her family). During her adolescence and teen years, she went by Berta, a Russian name. The two were married in their hometown on July 25, 1915. Their only child together, Ida Chagall, was born May 18, 1916, in Vitebsk, and they remained for only one year before moving to Paris in September 1923. Upon arrival, Berta became Bella, Moyshe became Marc, and their surname “Shagal” became “Chagall.” They lived in Paris until 1941, barely escaping the Nazi occupation of France. Thanks to the efforts of Varian Fry, they managed to make it to the United States. Ida Chagall and her first husband, Michel Rapaport, joined them shortly after, using every connection they had to save the paintings that Marc Chagall had left behind.

Though Bella Chagall had had a number of mysterious operations and illnesses while in Paris, friends and family were stunned by her sudden death in 1944 from streptococcal pharyngitis, strep throat (though her official death certificate reported “Diabetes Mellitus” as cause of death). She was buried with a simple gravestone in New Jersey, her name written in both Yiddish and English, with two hands raised in the priestly blessing, the symbol of the Kohanim (the high priests).

Mark Chagall’s relationship with Bella Chagall has been framed as the great and all-encompassing love; yet he had two marriages (one common-law and one legal) following her death. Not long after Bella Chagall passed away, he had a son with Virginia Haggard, the Chagall’s housekeeper upon their arrival in America, named David McClein (taking on the last name of Virginia Haggard’s husband). He remained in a common-law marriage with Haggard for seven years. When her husband finally granted her a divorce, she left Marc Chagall for the photographer Charles Leirens. Four months later, Marc Chagall married the housekeeper his daughter Ida had hired for him after Haggard had left, Valentina (Vava) Brodsky. He remained married to Vava Chagall until his death in 1985.

Still, Bella knew where Marc Chagall came from; she knew his language, his religion, and his connection to Russian Jewry intimately. Bella remained his heavenly bride and his angel in his art and poetry, even as he had additional romantic relationships.

Jewish Holidays:

Marc Chagall and the editors of the book structured the chapters using the Jewish holiday cycle, incorporating individual Jewish rituals and those perhaps considered ritual by Basha (for example, the first snow or dinnertime) along with the holidays.

This article on Interfaith Family’s website provides a helpful overview of the Jewish holidays; however, it is worth noting that there is no distinction in the article between holidays that are observed by Jews in the contemporary moment, and those that the Rosenfeld family would have observed in the nineteenth century (for example, Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, only became a holiday in the mid-20th century). For Jewish holiday descriptions with distinctions between biblical holidays, rabbinic holidays, and non-rabbinic holidays, consult the guide to Jewish holidays on My Jewish Learning.

Modern Representations:

After Marc Chagall died, the work of representing his estate was largely left to his and Bella’s only child together, Ida. She passed away in 1994, and her short obituary in the New York Times recalls her successful efforts to organize expositions of Marc Chagall’s work. The obituary also identifies the Israel Museum as the home for the drawings that Chagall created for Burning Lights and First Encounter. Ida Chagall gave these, and many other works by her father, to the museum in 1990. Her daughters, Bella and Meret Meyer, work to exhibit and represent their grandfather’s art as their mother had. They discuss their grandfather’s work in an interview for LACMA and in an interview with the New York Times at the Jewish Museum. Granddaughter Bella Meyer also discusses Bella and Marc Chagall’s relationship in an interview with Sotheby’s.

Marc Chagall’s illustrations for Burning Lights were not the only Yiddish text for which he created accompanying illustrations. There are some beautiful examples of his work in the Yiddish Book Center’s Digital Yiddish Library.

Marc Chagall's Illustrations in Yiddish Literature

Bella and Marc Chagall’s relationship lives on. Emma Rice recently directed a show entitled The Flying Lovers of Vitebsk. Alongside the trailer for the performance is a description of the show, a theatrical piece through which “Marc and Bell Chagall are immortalized as the picture of romance.”

Museums continue to exhibit Marc Chagall’s work, often focusing on Bella’s key role as his muse:

- The Jewish Museum’s exhibit in 2014, Marc Chagall: Love, War, Exile, covered the years 1930–1948 and focused particularly on the tumultuous years leading up to and following Bella’s death.

- Sotheby’s wrote an article about Double Portrait with Wine Glass, one of Marc Chagall’s many wedding portraits of him and Bella Chagall.

- The Marc Chagall Museum in Vitebsk has a large permanent collection of his work.

- The Marc Chagall National Museum in Nice, France, is dedicated to his work.

Discussion Questions:

- Does the title Burning Lights accurately reflect the content of the memoir? According to letters, it wasn’t Bella but Marc Chagall who selected the title, as well as the chapter titles. What impact did these choices have on the way you understand the book?

- Bella Chagall weaves anthropomorphism throughout the chapters of the book: giving animals, plants, water, and even furniture human characteristics. Why? What sense does this give of her way of thinking about the world around her?

- What sense does the memoir give you of Vitebsk as a town in the late 19th century? What details of local life aren’t included in her memories?

- Do the celebrations of Jewish holidays recounted here seem familiar to you, or are they observed in ways that are quite different from what you’ve experienced or heard about elsewhere? What surprises you about the rituals and celebrations Chagall describes?

- Why do you think the opening chapter, “Heritage,” was selected to begin the book? Thinking about her only child, Ida, Bella Chagall asks, “Will she understand me?” What do you think she means by the question? What kind of understanding is she anxious about?

- In her introduction, Bella Chagall describes the challenge of writing a memoir: “It is so hard to draw out a fragment of life from fleshless memories!” How does she bring “life” into these short chapters?

- How do Marc Chagall’s illustrations interact with the text written by Bella Chagall? Do you find them meaningful? An elevation? A distraction?

- If you were familiar with Marc Chagall’s celebrated paintings before reading the memoir, does the memoir change the way you think about them? How so?

—Sarah Quiat