"Immodestly Yours..." Sometimes the inscriptions are as interesting as the books themselves

Some books tell their own stories.

- Written by:

- David Mazower

- Published:

- Fall 2011 / 5772

- Part of issue number:

- 64

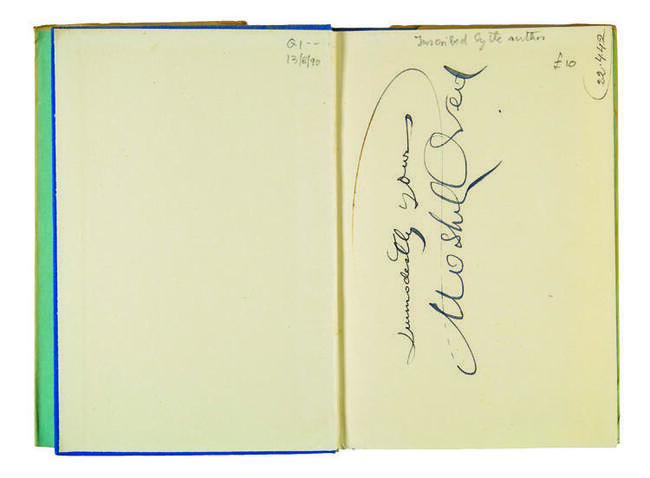

I realized this about twenty years ago while browsing in a secondhand Jewish bookstore in north London. The owner had just bought a library that had belonged to the Yiddish journalist Josef Fraenkel, and almost all of the hundreds of books carried personal dedications from their authors. A volume of travel sketches by Arn Vergelis, the editor of Sovetish heymland and one of the few postwar Soviet Yiddish writers permitted to travel to the West, was a gift to Fraenkel, “mayn alter bekanter” (my old acquaintance), from a meeting in Moscow in 1976. The jeweler and romantic Zionist poet Mosheh Oved had signed several of his books “Immodestly yours” with an extrovert’s flourish. The best-selling Polish Yiddish author Zusman Segalowitch had visited London in 1923 and warmly dedicated several books (to a commercial traveler by the name of Yankev Slivko ( (“dem libn yudnun landsman. . . Mister Slivko”/to the dear Jew and compatriot . . . Mr. Slivko) and these too had passed into Fraenkel’s library.

Intrigued by these clues to a vanished literary world, I began to collect Yiddish books signed by their authors. Today my collection fills several bookcases and includes books published in Winnipeg and Wales, Melbourne and Mexico City, Havana and Haifa. The earliest volume is a present from a young poet to an established writer and editor: Naftoli Gross’s Psalmen (Psalms), published in New York in 1918, is “a matone dem lieben zeyden Moris Vintshevski” (a present to our beloved grandfather Morris Winchevsky). The authors range from poets, novelists, storytellers, and actors to literary critics, journalists, humorists, and artists. The books are dedicated to readers, editors, friends, colleagues, and comrades. They are a microcosm of a literary culture that spanned the globe, and they reflect lives marked by war, poverty, dislocation, and exile.

The personal greetings are respectful, intimate, defiant, and, at times, almost unbearably poignant. The Holocaust survivor and former partisan fighter Szmerke Kaczerginski inscribed a book of wartime memoirs “mit partizanishn grus” (with partisan greetings). In 1943, the year of Moyshe Nadir’s death, his widow Zhenia dedicated one of his books to the New York Yiddish teacher Leybush Shpitalnik “mit a gebrokhn harts vos ikh onshtot Nadir oytografirt dos bukh” (with a broken heart that it is I signing this book and not Nadir). By contrast, the Yiddish actress Molly Picon was always upbeat, adding a smiling face to her signature, and the poet Menke Katz delighted in long inscriptions with extravagant floral decorations. One of my most treasured possessions is a book Itzik Manger presented in London to his friend and fellow exile, the Polish Bundist leader Shmuel Mordekhe (Artur) Zygielbojm, during the darkest days of World War II. The dedication: “Artur Ziglboym mit libshaft 1942” (to Artur Zygielbojm with love, 1942). Shortly afterward, Zygielbojm committed suicide to shock the world into paying attention to the terrible news emerging from Poland. The book passed into the hands of a fellow Bundist, Markus Klok, whose widow gave it to me years later in memory of my own Bundist grandfather.

History casts a long shadow over any Yiddish book collection. To the best of my knowledge, not a single book signed by Sholem Aleichem, Peretz, or Mendele has come up for sale in the past twenty years. But I did manage to acquire some books from the library of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Gifts from fellow writers, they were bought by a New York book dealer after Bashevis’s death and sold for 25 dollars each. They are a master class in the lexicon of flattery. From Melbourne, novelist Hertz Bergner addresses Bashevis as “mayn tayern khaver, dem velt-barimtn proze-mayster” (my dear friend, the world-famous prose master); Avrom Karpinovitsh, one of the last chroniclers of prewar Vilna, writes to “Bashevis-Zinger, dem shrayber vos kh’bin im mekane zayn talant” (Bashevis Singer, the writer whose talent I envy). But when the elderly Avrom Reisen sends Bashevis his collected poems in 1951, shortly before Reisen’s death, he writes as an equal with a more playful tone: “A matone mamesh, mayn libn gaystraykhn kolege, groysn novelist un esayist, Yitskhok Bashevis, mit farerung” (A true present! To my dear brilliant colleague, the great novelist and essayist Isaac Bashevis, with respect).

My own favorites? One is a volume of memoirs by the German anarchist thinker Rudolf Rocker. The non-Jewish Rocker learned Yiddish in London’s East End in the 1890s. He soon spoke it well enough to address mass rallies and typeset a Yiddish anarchist newspaper; he was revered by a generation of Jewish comrades. Before he fled Berlin for New York in the 1930s, he published an account of his internment as an enemy alien in Britain during World War I. The rare limited Yiddish edition is hand-signed by Rocker in his neat Yiddish script: “Berlin, februar, 1927. R. Roker." Just a few words, but they speak volumes about Rocker’s extraordinary dedication to the Jewish workers’ cause.

I found another favorite in a bookseller’s attic in Brooklyn among discarded prams and baby clothes. It’s Itzik Manger’s Lid un balade, the volume of collected poems he published in 1952, soon after arriving in New York from London. The regular edition is lavish enough. But this copy is unique: a one-off imprint on thick green paper, it is dedicated to Margaret Waterhouse, the London bookseller who befriended and lived with the refugee poet for a decade. Manger’s relationships with friends and lovers were rarely untroubled—his legendary boozing and bohemian ways saw to that. In America, he soon married Moyshe Nadir’s widow. But this handsome volume, with its brief English inscription, is a sign of Manger’s gratitude to the woman described by one mutual friend as “Manger’s ministering angel.”

Perhaps this book has its own guardian angel. After all, it has now crossed the Atlantic no fewer than three times. Like all these personalized mementos, it has much to tell us about the Yiddish literary world and the networks of patronage, commerce, and friendship that sustained it. If only books could talk, the saying goes. Luckily for us, these can.

David Mazower, great-grandson of Sholem Asch, is a news program editor with BBC World Service radio in London.