Kadya Molodovsky: A Woman Novelist Rediscovered

- Written by:

- Anita Norich

- Published:

- Fall 2017 / 5778

- Part of issue number:

- 76

I recently finished translating Fun lublin biz nyu york (From Lublin to New York), a novel by the Yiddish writer Kadya Molodovsky, for Indiana University Press. While working on the introduction I went to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research to check a few details about Molodovsky’s publishing history. Like most writers’ archives, Molodovsky’s papers are the usual assortment of notes and clippings and drafts—interesting to a specialist but not many others. When I opened up those dusty boxes, however, what I found transformed what I thought I knew about Molodovsky—and about Yiddish literature in general.

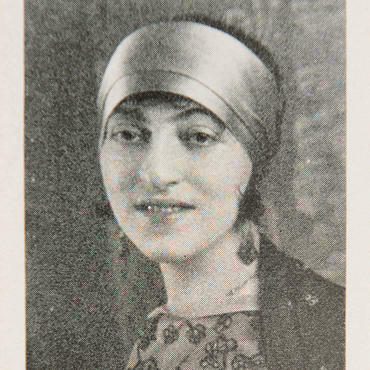

Kadya Molodovsky, arguably the best-known female writer of Yiddish, is renowned as an editor, a poet, a critic, a playwright, and a short story writer. Born in 1894 in what is now Belarus, she traveled throughout Poland and Ukraine as a young adult, studying, writing, teaching, and working in homes for orphaned refugees. In 1921 she moved to Warsaw and spent the next fourteen years teaching in various Hebrew and Yiddish schools, writing poetry, and contributing to Yiddish literary journals. Her poetry was later translated into Hebrew by Natan Alterman and Leah Goldberg, two of the most important Hebrew poets of the twentieth century. For decades she has been part of the Israeli school curriculum, and children and their teachers often recite or sing her poems without knowing that they were originally written in Yiddish. (Kathryn Hellerstein has given us a wonderful book of English translations of her poetry, and there are a few translations of her short stories into English.) In 1935 Molodovsky emigrated to the United States, where she began contributing to the New York Yiddish press and, for the first time, writing novels.

Until now, Molodovsky has been credited with just two full-length works of fiction: From Lublin to New York, which she published in 1942, and Baym toyer (At the Gate), from 1967. From Lublin to New York tells the story of Rivke Zilberg, a twenty-year-old woman who flees the Nazis and comes to her aunt’s home in New York. Rivke keeps a journal that begins on December 15, 1939, and ends ten months later, on October 6, 1940. In 107 journal entries, the reader encounters the story of a refugee acutely aware of the danger left behind. Knowing of her mother’s death in the German bombing of Lublin, unsure of the fate of her father, brothers, or the man she was to marry, Rivke must now contend with the difficulties of immigration.

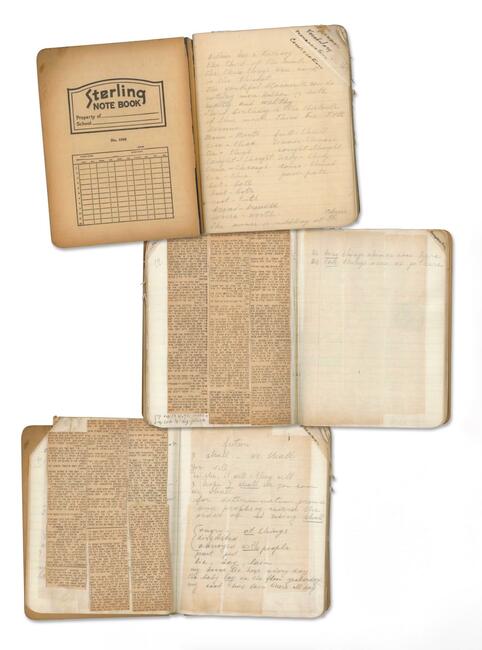

One of the major concerns of the novel is Rivke’s slow and incomplete mastery of English, and I wanted to see if there were any clues to Molodovsky’s own process of learning the language. To my delight YIVO’s finding aid pointed me to one of those black and white Sterling composition books that people of a certain age remember well. It was divided into sections titled Conversation, Pronunciation, Vocabulary, and Grammar, and I saw her handwritten exercises for each topic. Under Pronunciation she wrote “mouse/mouth,” “thrill-frill,” and more. She practiced tenses and idioms and prepositions (“angry at things”; “annoyed with people”). That was just the beginning of my findings.

After some hunting through newspaper microfilm I discovered that the character didn’t end with the novel.

After the novel’s publication, you might expect to have seen the last of Rivke Zilberg. But after some hunting through newspaper microfilm I discovered that the character didn’t end with the novel. Between 1954 and 1956 Molodovsky contributed a series of columns for the Forverts titled Portretn fun froyen (Portraits of Women). What’s more, she had written them under the name Rivke Zilberg. This was no mere pseudonym. For Molodovsky, Zilberg had become an entire persona (rather like, for example, Mendele Moykher-Sforim) that she created over several years.

Rivke Zilberg’s experiences bear some resemblance to Molodovsky’s. Like her creator, Zilberg struggles over immigration and language acquisition and fears the unfolding events in Europe and the fate of her family. There are important differences too, like her age, place of emigration, and marital status. But it’s as if, in these articles, Molodovsky is hinting at what the twenty-year-old refugee might have become after fifteen or twenty years in America: a writer and an intellectual interested in feminist questions—in other words, a woman something like Molodovsky herself.

As Molodovsky’s translator, this was invaluable information. But what I soon learned showed that Molodovsky’s literary output—particularly as a novelist—exceeded anything that I, or anyone else, had suspected.

In one folder of Molodovsky’s archive I saw what looked like a novel or collection of stories, the first of which bore the name of a character, Hymie Kravitz. It was typed on fraying paper, and the last page was torn at the bottom. Was this the end of a manuscript? Was there more? The answer, it turned out, was in Molodovsky’s grammar exercises. When I turned the pages of those drills I saw neatly pasted newspaper clippings that continued through most of two Sterling notebooks. Only the first page had a title and a handwritten date and place of publication: “Zeydes un eyniklekh [Grandfathers and Grandchildren], Morgn zshurnal, Oct. 13, 1948.” The first installment was titled “Hymie Kravitz”—the very name I had seen on those frayed pages. Another run at the microfilm showed that the novel was published daily, except Saturday, until December 28, 1948. To my surprise, I had found a third novel by Molodovsky—a novel that had never been discussed in any analyses of Molodovsky’s writings.

And there was more. While searching through the archive I found a reference to yet another novel entitled Di yerushe (The Inheritance). When I went to look for it, however, it wasn’t there—in the folder where it was supposed to be, I found Molodovsky’s memoir instead. But after chasing through folders of her archive I eventually found a list of completed sections and six handwritten, unpublished chapters. Earlier parts of the novel, published in Molodovsky’s own journal, Svive, turned up in yet another folder. Thirteen more chapters had been published between February 1944 and February 1945 in the weekly Der yidisher kemfer (The Jew Militant). It turned out that Molodovsky had written at least twenty-one chapters of this previously unnoticed novel.

Their broad themes concern generational conflict, family life, the position of women, and the inability of Holocaust survivors, Israelis, and American Jews to imagine one another’s lives.

I wondered why I had never heard of these novels and why they were not mentioned in any Yiddish or English publication I had read. (Later I learned that a Hebrew MA thesis by Amir Shomroni listed them.) Unlike Fun lublin biz nyu york and the later Zeydes un eyniklekh, Di yerushe turned out not to be Molodovsky’s best work, and it was probably unfinished for the same reasons that Molodovsky stopped editing Svive: financial pressures, desperate worry about the murder of Poland’s Jews, and health concerns, including surgery on her hand. She had hoped to publish Zeydes un eyniklekh as a book, but her emigration to Israel just after the novel’s serialization may have put an end to that plan. Further archival research, perhaps, will reveal other explanations.

But all of the novels serialized in the 1940s are of historical and literary importance. They are all about characters who fled or survived the Nazis, and they depict these characters’ interactions with Jews in New York or the Catskills. Their broad themes concern generational conflict, family life, the position of women, and the inability of Holocaust survivors, Israelis, and American Jews to imagine one another’s lives. They are a combination of immigrant novels, coming-of-age stories, and Holocaust narratives. And they underscore the fact that Molodovsky’s primary concern in most of her poetry and prose is the meaning of yerushe: not inheritance in the sense of material things but of values, beliefs, yiddishkeyt.

The fact that there are more of these novels than we knew about is equally significant. Everyone who has ever read, researched, or written about Yiddish literature knows that there are a disheartening number of authors and texts published in the pages of Yiddish periodicals but now largely unknown. The only way to find them is by searching in archives and by turning the pages (or scrolling through the microfilm) of scores of periodicals. It is a frustrating, tedious, and incredibly exciting task, where you feel like a combination of sleuth, explorer, archaeologist, and obsessive. Finds like these demonstrate the vital importance of archival and bibliographical research and the importance of translation projects.

Just as important, these novels show that assumptions about genre and gender in Yiddish literature need to be altered. Women who wrote in Yiddish are almost always known as poets and not prose writers. There have been critical analyses and translations of Yiddish women’s poetry and even of short stories, but novels have long been considered a man’s genre in Yiddish belles lettres. But women wrote fiction in greater numbers than most of us know. And Molodovsky and other women whose works are in the pages of the Yiddish periodical press were not primarily concerned with domestic issues (i.e., “women’s concerns”) as some have argued but engaged those and other issues on a broad world-historical plane. Who knows what other treasures are out there, lying in a dusty archive folder or on some abandoned roll of microfilm? We need to keep finding texts and naming names.

Anita Norich is the Tikva Frymer-Kensky Collegiate Professor of English and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. She is most recently the author of Writing in Tongues: Yiddish Translation in the Twentieth Century (University of Washington Press, 2013) and Discovering Exile: Yiddish and Jewish American Literature in America During the Holocaust (Stanford, 2007).