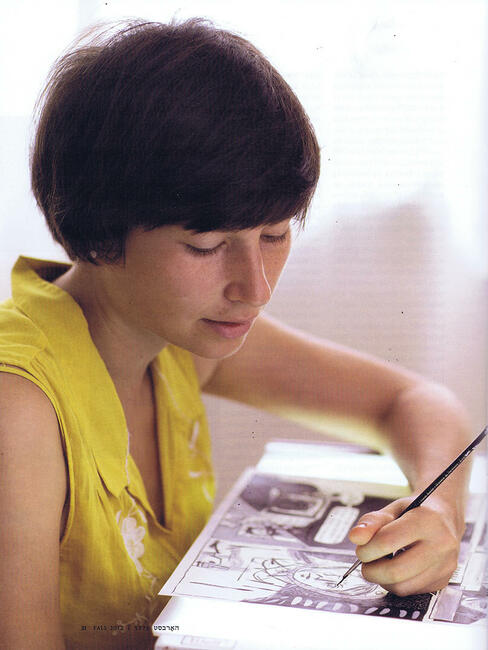

Liana Finck: Yiddish Graphic Novelist

- Written by:

- John Marchese

- Published:

- Fall 2012 / 5773

- Part of issue number:

- 66

In 2010, flush with a foundation grant, the then twenty-four-year-old comic artist did some intensive language study before she started searching through microfilm of century-old letters written in Yiddish by new immigrants to New York. They had been published in the Forward newspaper in an advice column that became known as the “Bintel Brief.” Intensely human, sometimes comic, often heartbreaking, some of those letters have become the basis for Finck’s graphic novel A Bintel Brief. It will be on exhibit at the Yiddish Book Center Spring 2013.

The original Bintel Brief was the brainchild of the Forward’s pioneering editor, Abraham Cahan, whom Finck describes as “kind of like a Jewish Ben Franklin.”

“He’s someone who’s worth loving,” says Finck. “He was a Renaissance man. He wrote novels. He started out as a firebrand socialist in Russia, but when he came here he became more of a populist. He just wanted to do good for these poor, uneducated people.”

Cahan’s advice column answering letters from these mostly poor and variably educated Jewish immigrants in New York became one of the most popular features in the Forward, and the Bintel Brief ran there for decades. “The early letters were the best,” Finck says, “because they were written by these young people with tragic lives. The late letters are mostly by people who are pissed off at their grandchildren because they’re not speaking Yiddish.”

Of course, Finck was one of those grandchildren. Her father, a doctor, and her mother, an architect and artist, raised her in a small rural town in upstate New York. “My parents had both grown up orthodox in Brooklyn and Queens,” she says. “Both abandoned Judaism and became slightly hippie in college. When they met, in their thirties, they decided to become Jewish again in a modified way. We were Conservative Jews, and I went to Conservative Hebrew day school and learned Torah. I loved that part.”

“I was trying to rediscover the person I’d been ignoring since I started college. I thought it would be interesting to write about something Jewish.” She remembered a book her grandmother had given her, a collection of Bintel Brief letters translated into English. They captured her imagination.

Like her parents, Finck largely left religion behind when she spent four years studying at the prestigious Cooper Union art school in Manhattan. Then she spent a year in Belgium on a Fulbright Scholarship, where she worked on a comic book based on the life of another cartoonist—Georges Remi, the Belgian who drew the famous Tintin series. It remains unfinished.

After she returned to New York and set about starting a career as a cartoonist, Finck says, “I was trying to rediscover the person I’d been ignoring since I started college. I thought it would be interesting to write about something Jewish.” She remembered a book her grandmother had given her, a collection of Bintel Brief letters translated into English. They captured her imagination.

“I feel very deeply connected with the stories,” she says, “and the mood of struggling and the very, very wry humor. I’ve always been on and off interested in Yiddish, because it seems like this secret counterculture of Judaism. I’m keeping all my Yiddish textbooks, because I have a feeling I’ll get the urge to come back to it. I think it’s something I have in my blood. There are a lot of things in Judaism that I can’t relate to, but I can relate to this weird, salty, cartoonish language.”