The Maximalist’s Daughter

- Written by:

- Aaron Lansky

- Published:

- Fall 2017 / 5777

- Part of issue number:

- 75

It took Mordkhe Schaechter a lifetime to collect a million Yiddish words and phrases. It took his daughter, Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath, sixteen years to turn them into a dictionary.

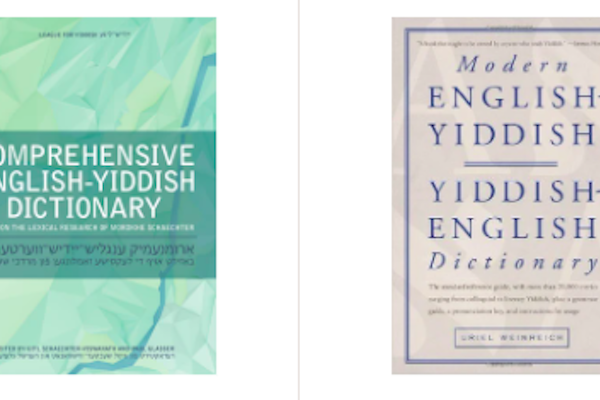

Aaron Lansky: There have been many Yiddish dictionaries over the years, starting with Harkavy in 1898; the multi-volume Groyser verterbukh (The Great Dictionary), which never got beyond the letter alef; Weinreich’s Modern English-Yiddish/Yiddish-English Dictionary in 1968; and most recently Beinfeld and Bochner’s Comprehensive Yiddish-English Dictionary, based on Yitskhok Niborski’s excellent Yiddish-French Dictionary. How is your dictionary—which you co-edited with Paul Glasser—different from all other Yiddish dictionaries?

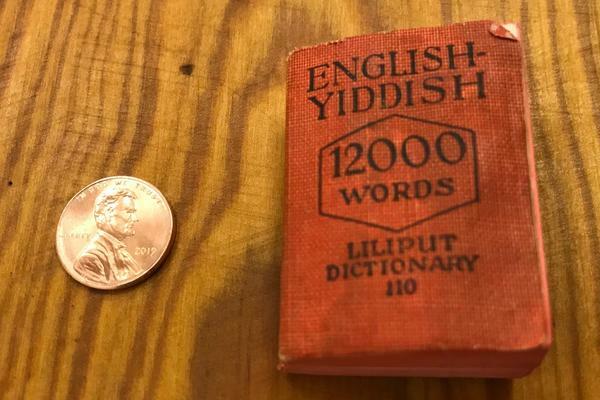

Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath: The most recent dictionary [by Beinfeld and Bochner] is Yiddish-English. Ours is English-Yiddish. Why did we need it? Because the most recent English-Yiddish dictionary was Uriel Weinreich’s, in 1968. That was almost fifty years ago. Several generations have come and gone in that time. The dictionary itself only had 20,000 words. A little-known fact about Weinreich’s dictionary is that this was supposed to be a first edition: Weinreich had every intention of expanding it, of adding more words. Unfortunately, he died at a very young age and he didn’t even live to see his dictionary in print, so it was never expanded. It was stuck in 1968, so to speak. We live in a time now where there are thousands of words that didn’t even exist back then. And there were tens of thousands of words that never made it into Weinreich’s dictionary in the first place. Our new dictionary has about 50,000 entries and 33,000 subentries, for a total of 83,000 words and expressions!

You knew my father, Mordkhe Schaechter, on whose work this new dictionary was based?

Aaron: Of course, he was my teacher.

Gitl: Well, he was a maximalist, and I drank that in with my mother’s milk. I also am a maximalist, which is probably why it took sixteen years to complete this dictionary. I couldn’t let go until I’d included everything. Of course, it doesn’t have everything, but I went as far as I could go with it. It has words that you could find in literature a hundred years ago that never made it into a dictionary. You’ll find words that were in the Yiddish textbooks that were used in the Yiddish schools of Eastern Europe between the two world wars, words about science and sports and the military and all those words that were used in Eastern Europe that never made it into an English-Yiddish dictionary before.

Aaron: There have been many press accounts about the dictionary, and they all seem to focus on the neologisms, the dictionary’s newly coined Yiddish words. For some reason or another, reports seem to love “blitspost,” the Yiddish word for “email.” Out of 83,000 words, how many are newly coined, and why do people find them so fascinating?

Gitl: When you write an article, you need a hook. The New York Times ran a great article on the dictionary; its hook was new words, and that’s why it went viral. Journalists started calling us from all over the world, and everybody loved the neologisms. Approximately seven percent of the words are new coinages. You have to ask yourself, what is a new coinage? Is it a word that was coined in the last five years? Is it a word that was coined in the last sixty years? There were people who were very upset with Weinreich fifty years ago because he included a couple hundred neologisms in his dictionary. He also believed in coining words when we need them. But other people, they’re not happy with it, for whatever reason: conservatism, or a lack of optimism about the future. Neologisms are tough to define. Take the car, the automobile. We needed to have a word for car in 1873 when the first car was produced, so is that a neologism? It’s a tough question, but a huge percentage of words in our dictionary, at least 90 percent, existed previously. We didn’t invent them.

Aaron: Can you give me an example of a few of the more interesting neologisms?

Gitl: A word in a new language, in any new language, whether it’s created by the Académie française or any other language institute, has to not just translate the meaning of the word but to embody the flavor of the language. We tried as much as possible to use Yiddish constructions, grammatical structures, prefixes, suffixes, diminutives, Slavic endings, Germanic endings, all the word forms and roots that we have in Yiddish that we can combine to make a word that we would consider yidishlekh, that has that special Yiddish something. There were a number of words that Hershl [Paul Glasser] and I banged our heads against the wall about and some we ended up leaving out. This is an example that I coined, and it was one of the most recent ones, which is why it’s in my head: the Yiddish word for “binge watch.”

Aaron: I barely know what that word means in English. It means to watch a ton of episodes of a TV show, is that right?

Gitl: All in one sitting. You record them and then you watch them all at once. It’s very popular where I live. I guess it’s not popular where you live.

Aaron: We haven’t owned a TV set for forty years, so I’m not the best person to ask.

Gitl: In Yiddish we have an expression, shlingen bikher, meaning a person who’s a bookworm, who loves to read, who swallows or devours books. So we were thinking, what exactly is binge watching? It is essentially devouring episodes of a particular series. I just came up with shlingen epizodn. The people who are involved in the dictionary liked it, and we included it.

Aaron: I read both of Simon Winchester’s books on the making of the Oxford English Dictionary. Compiling the first edition took seventy-one years! You and your colleagues, Hershl Glasser and [associate editor] Chava Lapin, completed this dictionary in, what, sixteen years?

Gitl: Yes, sixteen, but I can’t compare it to the OED.

Aaron: We’ll let our readers decide that. Of course, you didn’t exactly start from scratch. This was based on your father’s lifetime of research. Can you tell me a bit about your father? Who was he, and why was he so committed to collecting and defining Yiddish words?

Gitl: Mordkhe Schaechter came from a strongly Yiddishist home. His father walked by foot to attend the historic Yiddish conference in Czernowitz in 1908, where Yiddish was declared a national language of the Jewish people. My father earned a PhD in linguistics. He came to America after the war and became a Yiddish professor at Columbia. He loved to collect words. As a field researcher for the Kulturatlas, the Atlas of Yiddish Language and Culture, he would go out in the field with a huge tape recorder and record people who had come from Europe. He would speak to the tailor and the shoemaker and the former soldier and the former weightlifter and people who did all sorts of different things in Eastern Europe, and my father would record how they spoke and what they said and the words they used. He would tape record it, and he then subsequently transcribed [the interviews] onto index cards.

Anyone who knew my father never saw him without an index card and a pen. Whenever he spoke to you, he was always writing down words, words that were interesting to him, words that he had never heard or that he had heard from his grandmother but hadn’t heard for the last thirty years. All words were fascinating to him, all Yiddish words. He ended up with eighty-seven card catalogs and shoe boxes full of index cards.

His goal, among many others—too many—was to create terminological dictionaries: one for this topic and one for that topic. In the end they all were. . . what’s the word I’m looking for? They were aggregated into one, and it was going to come out as a dictionary. But he didn’t get to it until the year 2000. I worked with him on it. I actually computerized those cards during the 1990s.

Aaron: Is it true there were a million cards?

Gitl: Oh, yes.

Aaron: Really?

Gitl: You know what, I believe there were a million words. There could have been several words on a card. Some cards could have eight words on them, words that were related in some way.

Aaron: Still, it’s astonishing, Gitl. I remember going to your family’s house. In 1977 I was a student in the zumer-program, the YIVO summer program at Columbia, and your father was my teacher. Oh, my God, what an experience that was! One evening he invited the whole class over to your house [on Bainbridge Avenue in the Bronx]. I remember sitting there, and someone pointed to an adjacent room. I seem to remember an old wooden card catalog. Someone explained in a hushed tone, “Ot zenen di kartlekh—there are the cards.” Was your whole house taken over by the kartlekh?

Gitl: No. I think my mother made him keep them in the den in his workspace. But my father was a voracious reader—er hot geshlungen tsaytungen [he devoured newspapers]. Every single Yiddish newspaper or magazine that was being published was in our house. My father read them all, looking not for the news but for words. You can’t imagine what our childhood dining room table looked like. It was full of newspapers and clippings, and those also made it into the card catalog. He and I started working on it in 2000. He unfortunately became ill two years later, and he was really not able to continue with it. I had already been working with him on it, and I was one of his right hands over several decades. He never asked me directly, but I felt that at this stage of the game, we couldn’t not do something with all this. At the time, I had a husband and three young children and a day job as a nurse. Every evening, whenever I could get an hour or two, I would sit at the dining room table and work, editing and adding words. This went on pretty much for sixteen years.

As each of my children left the nest, I had more time. When I came home from work I would grab a cup of coffee and something to eat, then sit down at the dining room table and work until I dropped. When I look back on it, I don’t know how I didn’t become ill myself. There were times when I was very, very, very upset because I didn’t feel the dictionary would ever be published.

I’ll tell you one example. We started this on an old eMac. When I upgraded the software, the fonts we were using from the 1990s were no longer compatible. That I think was my low point because we had the manuscript and I had no idea how we were going to publish it. We resolved the issue. A young man named Jamie Conway came into my daughter’s life and subsequently married her. He’s a math PhD with great computer skills. I showed him the file, and he was able to convert it into another computer language, and then he reconverted it into Yiddish and made PDFs. From that point onward, all the editing was done on PDFs rather than text.

Aaron: That’s difficult, though, right?

Gitl: This really is a nes min hashomayim—it was a miracle from heaven because I was in constant fear of the eMac dying on me. It never died, by the way. I still have it. I don’t know what to do with it. I don’t know which unique museum would want an eMac.

Aaron: It sounds like a museum piece. You could exhibit it next to your father’s card catalog.

Gitl: That’s how the project ended up being finished.

Aaron: Fantastic. Had your father ever made the leap to technology?

Gitl: He wrote e-mails. He was able to write e-mails, yes, in the last years of his life, but beyond that . . .He died in 2007. I think after 2003, he wasn’t even using the computer anymore. There was no Facebook and Twitter and all that, which I don’t do either. He was capable of communicating by e-mail.

Aaron: Was he supportive of your efforts to digitize this material, to put it online?

Gitl: Oh, yes, no question. He understood that we needed to do that.

Aaron: So he was forward looking?

Gitl: Yes, no question. You couldn’t have the kinds of words that he had on his cards (and we have in the dictionary) and not be forward thinking. He wanted to include the terminology for astronomy and sciences and everything future—everything present, past, and future—because for him, and for me as well . . . some people might say we stick our heads in the sand, but we see a future for Yiddish. Yiddish might look different than what we’re speaking or writing now, but we don’t see it dying anytime soon, and I’m sure you understand that.

Aaron: Of course.

Gitl: Yes. We’re forward speaking, forward looking, forward searching.

Aaron: I have a more personal question for you. How come, out of all your siblings, you were the one who became involved with this project?

Gitl: Good question. There were four of us; I’m the second oldest. I think my father saw something in me. He saw an interest, and I was always interested in helping him. What can I say? When I was about twelve, those clippings that I mentioned on the dining room table—he came to me one Saturday night and he said, “Volstu gevolt helfn mit mayn arbet, would you like to help me with my work?” He said he would pay me. He paid me, I don’t know, a nickel, a quarter, whatever it was, and for a few hours he and I would sit. This was quality time. Forget watching TV together. This was my quality time with my father, sitting together and going through these clippings and just writing the bibliographical information, where the clipping is from, and then stapling it to an index card and putting it in the card catalog. It really was clerical on my part, but while we were doing it, he would show me this work, he would tell me about that author. That’s how I started on that path.

"This was my quality time with my father, sitting together and going through these clippings and just writing the bibliographical information, where the clipping is from, and then stapling it to an index card and putting it in the card catalog."

I also happen to have had a good eye for finding typos. I became an editor at Yugntruf [Youth for Yiddish]. Then I was an editor at Afn shvel [On the Threshold]. I continue to be the Yiddish-language editor of Afn shvel today. That’s the magazine of the League for Yiddish, which was founded by my father in the 1980s. It still exists today. It holds the copyright for the dictionary, and all proceeds from the sale of the dictionary go to the League for Yiddish. That’s what he would have wanted. It’s the only organization out there that still fights for a high level, a level of prestige, for the Yiddish language, that it shouldn’t be just for nostalgia and it shouldn’t be made fun of or laughed at. All the other things you hear about Yiddish, such as that it’s only a language of blessings and curses or that it has no word for ceiling, those kinds of urban legends . . .

Aaron: It would have been anathema to your father, that idea, right? The trivialization of Yiddish.

Gitl: Of course, right. I also want to mention, in case you don’t know, that the League for Yiddish has a Facebook page, and on that page, on a weekly basis, we put a thematic list called Verter fun der vokh, Words of the Week. Last week, it was dental work. Next week, it’ll be Purim. A few weeks ago it was construction. Adam Whiteman helps me with it. Whatever’s going on, either seasonally or in terms of yontef [a Jewish holiday] or in terms of the news, politics—anything is a good reason to learn new Yiddish words. I would encourage whoever’s reading this article to go to the Facebook page for the League for Yiddish and “like” the Words of the Week. It would be really helpful for us in terms of spreading these words and expressions.

Aaron: I need to go there myself. I went to the periodontist recently. I walk in, sit down in the chair, and while I’m waiting for the doctor to show up I notice a mezuzah on the door. I wasn’t quite sure what that portended. The doctor comes in, and he’s a Lubavitcher khosid, which is maybe commonplace where you are but here in western Massachusetts it’s a bit unusual. It turned out he was actually a baltshuve, somebody who had become Hasidic, but had learned Yiddish along the way, and he proceeded to speak with me in Yiddish for quite some time while the hygienist looked on in amazement. I’ve got another appointment next week, and I’m going to wow him with Yiddish dental terminology!

Gitl: Good. How did he know that you speak Yiddish?

Aaron: It’s a small community. Okay, on to another question, Gitl: What do you do for a day job, when you’re not working as a Yiddish lexicographer?

Gitl: Many, many decades ago, I went to nursing school, so I am an RN, although I haven’t touched a patient in thirty-five years. For several decades I’ve been a nursing-home consultant. Every day I go to different nursing homes and offer them my wisdom and advice about Medicare or Medicaid reimbursements. That has paid the bills, it has paid my children’s tuition, it has made it possible for me to work on the dictionary without taking any payment. All around it’s been a very good profession for me.

Aaron: You remind me of Kafka, who used to work in an insurance office and then come home and write this extraordinary literature. You have a whole other life.

Gitl: I don’t think Kafka enjoyed his job. Did he enjoy being an insurance broker?

Aaron: I’m not sure he enjoyed anything, but it sounds as though you love what you do. The dictionary is an extraordinary labor of love. I have another question for you: Did you ever see a little booklet called Say It in Yiddish? It was a Yiddish travel guide and phrase book compiled in 1958 by Uriel Weinreich.

Gitl: Yes. I believe he did it together with his wife, Bina.

Aaron: That’s right.

Gitl: I remember years ago reading a critique of that book that was unnecessarily critical: Who needs these words? Who goes to a foreign country and speaks in Yiddish? What nonsense is this? I felt the article was so gratuitous. What was the writer’s agenda? Did they have to do that? Did they have to show the world that Yiddish toyg of kapores—is good for nothing? It was so out of the realm of . . .

Aaron: You’re absolutely right. That article was written by Michael Chabon [the acclaimed author of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay and The Yiddish Policemen’s Union].

Gitl: I didn’t know that.

Aaron: Yes, it was published in Civilization, the magazine of the Library of Congress, and it caused quite a stir. I think Chabon wrote it somewhat tongue in cheek. He wondered where in the world you would ever use Yiddish expressions like “What is the flight number?” “Can you fix the flat tire?” “Please call a taxi for me!” or “I need something for a tourniquet.” (I always wondered about that last one.) Anyway, Chabon had a line that stuck with me. He said that speaking Yiddish today is like “a tin can with no tin can on the other end of the string” or something to that effect.

Gitl: Yes, that sounds familiar.

Aaron: Let’s apply that same image to your dictionary, which tells us how to say 83,000 English words and phrases in excellent Yiddish. Who is it for?

Gitl: It’s for anyone who either speaks Yiddish and wants to learn more Yiddish. Or it’s for teachers. It is for Yiddish students. It is for the Yiddish writers and poets we have today who are still creative. It is for any professional who wants to know how to say these words in Yiddish. It’s for fathers and mothers who are raising their children with Yiddish, whether they be secular or traditional or Hasidic. We do know of Hasidim who are using the dictionary. I don’t know that the masses of the Hasidim are finding the dictionary. It’s not published by a religious press, it doesn’t have the haskome [endorsement] of a rabbi, which books need to have. You probably won’t find it in a Hasidic book store, but we do hear that people are using it in that community, or they’re borrowing it.

Recently, someone I know was walking on the street and bumped into somebody she knew who didn’t speak Yiddish fluently but who had recently written an article for the Yiddish Forward. That person had purchased a dictionary, and he said, “I never could have written that article without this dictionary.” That, to me, is a good example of what it’s for. It provides the words, the expressions, to be able to be fluent in Yiddish even if one isn’t in real life. You could write articles. You could teach yourself. One of the things that I’ve noticed among Yiddish students—and I’m sure it happens in any language environment—is that students tend to translate things word for word because they don’t know the idiomatic forms in Yiddish.

Aaron: What do you mean by “word for word”?

Gitl: You could say “Ikh gey shlofn—I’m going to sleep,” or you could say “Ikh leyg zikh in bet arayn” or “Ikh gey zikh tsuleygn.” There are more idiomatic ways of saying certain things than just translating “I am going to sleep.” In that particular case, there’s nothing wrong with it, but we strove to also supply expressions that are more idiomatic, that are more yidishlekh, in case people want to use them. Let me see—offhand I can’t think of another one. If I think of one . . .

Aaron: . . . at three in the morning? You’ll give me a call.

Gitl: There are hundreds of thousands. I can’t think of one right now.

Aaron: It’s not word-for-word correspondence. One has to translate the concept into the other language.

Gitl: Exactly. Exactly. Sometimes the translations are so wooden I want to cover my ears so I don’t hear it. It’s hard. There are people walking around who speak Yiddish, and I love it, I love it, they’re learning Yiddish. But they need help with figuring out how to say these things without just translating them on the spur of the moment and thinking, “Oh, how cute, I translated that into Yiddish.” But that’s not necessarily the best way of doing it. That way you end up with many “Yinglish” kind of words, lots of calques.

Aaron: I have to tell you, your dictionary has a place of honor on my own desk. I love it not only because I use it a lot but also because it’s a beacon of hope for me. It’s almost an act of resistance: its sheer existence means that Yiddish is still alive and still evolving.

"It’s almost an act of resistance: its sheer existence means that Yiddish is still alive and still evolving."

Gitl: Thank you. That is what it is. You should also know that there is an electronic version of the dictionary in the works.

Aaron: Fantastic.

Gitl: It’s complicated, very complicated. We thought it would be easier. It’s a project we’re working on, and we’re hoping that by next year we might have something, but it’s up in the air right now. We’re working on it.

Aaron: That’s wonderful. You’ll be sure to let me know when it’s ready and we’ll let everybody know, we’ll link to it. It sounds like a fantastic idea. Yiddish really is coming into the modern world.

Gitl: Right. I will also mention that the first edition of the print dictionary was 1,200 copies, and it sold out within six months.

Aaron: That’s astonishing.

Gitl: It is astonishing. There have been two more printings of a thousand copies each. In the fourth printing we were able to include approximately eighty additions and/or errata. It’s not a second edition, because the changes are too few to be considered a second edition, but this is what we’re doing to help move it along until we get an electronic dictionary.

Aaron: I love it. A hayntike velt—it’s a modern world. For those who want to purchase the Comprehensive English-Yiddish Dictionary, where should they go?

Gitl: They can go to leagueforyiddish.org. The dictionary itself costs $60, with a discount for teachers or clubs or groups who want to buy five copies or more. We encourage people to become members of the League for Yiddish and support the organization that published this dictionary. You get a discount when you buy a dictionary and become a member at the same time. You can do all of that at leagueforyiddish.org.

Aaron: Do you also get Afn shvel, the magazine of the League for Yiddish?

Gitl: Yes, Afn shvel comes out twice a year. It’s a hefty magazine of seventy to eighty pages, and it has all kinds of articles, some of them with footnotes to gloss words for people whose Yiddish is not that good yet. It helps to learn words while you’re reading Yiddish literature.

Aaron: What a terrific story this is, Gitl. I really want to thank you. S’kumt dir a yasher-koyekh, s’iz beemes a rizike arbet—it’s a monumental work, and we owe you an enormous debt of gratitude.

Gitl: A dank—s’iz a zkhus tsu mayn tatn—it’s my tribute to my father and all he was trying to accomplish.

Aaron: As his student, that brings tears to my eyes, it really does. He was one of the most remarkable people I’ve ever known. What a wonderful tribute to him, and what a wonderful culmination of his life’s work. Thank you!