The Illusionist

Guedale Tenenbaum and His Wondrous Gallery of Yiddish Portraits

- Written by:

- David Mazower and Lila Fabro

- Published:

- Fall 2018/5779

- Part of issue number:

- 78

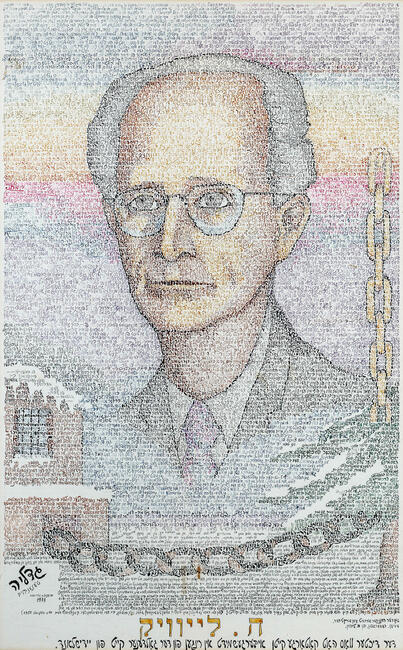

Earlier this year a remarkable image appeared on Facebook. It was a portrait of the Yiddish poet H. Leivick with all his features in micrography—miniature Yiddish letters almost invisible to the naked eye. The picture was posted by the Yiddish actor Shane Baker, who had come across it in Tel Aviv. It was signed “Guedale Tenenbaum, Buenos Aires.” Intrigued, we started to investigate this unknown artist. What we discovered was extraordinary: Tenenbaum was an immigrant textile worker who could barely afford basic art supplies, yet he created some of the finest Yiddish micrographs ever made.

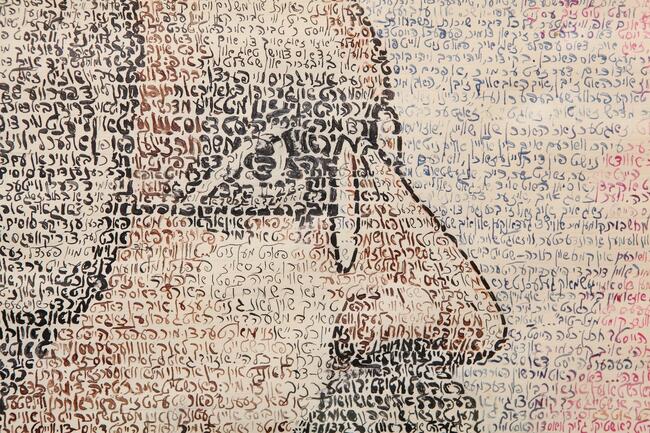

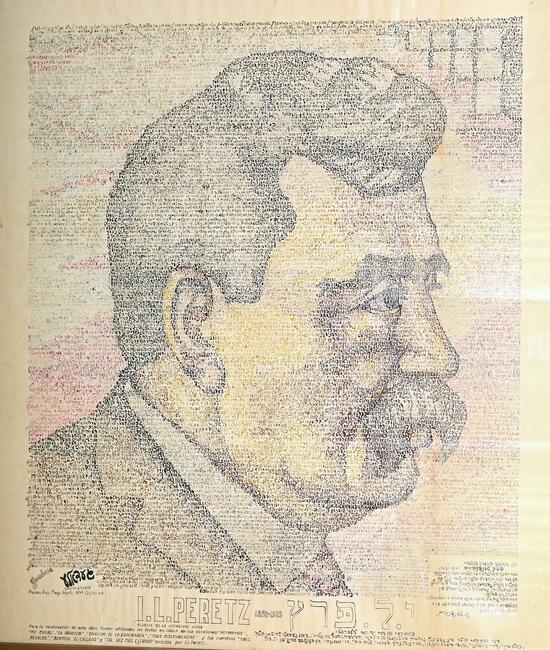

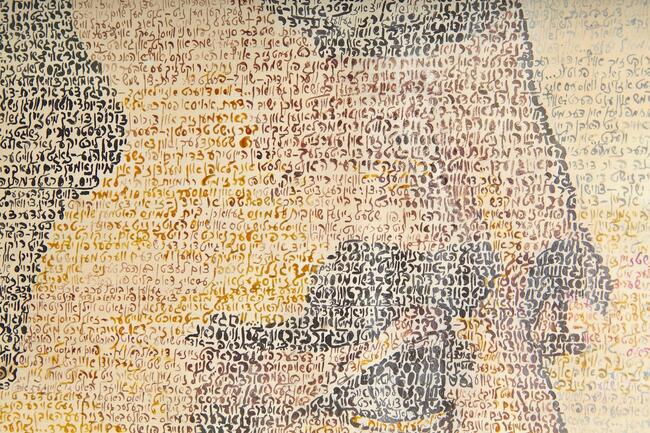

It was late one February evening in 1949 when Guedale Tenenbaum finally put the finishing touches to his portrait of the Yiddish writer Peretz. Midnight was approaching, his factory shift was long over, and his children were fast asleep. From the courtyard outside, snatches of conversation in Spanish and Yiddish floated in through the hallway of his Buenos Aires tenement. He lifted down the portrait for the last time, placed it flat on a table, took out his quill pens and bottle of black ink, and set to work. Well into the early hours, he painstakingly inked the last Yiddish letters into lines of cursive that stretched, looped, soared and plummeted. Over eight months of late-night sessions, the scattered lines gradually merged into a micrograph: a text-based picture made up of thousands of letters drawn from some of the writer’s best-known poems and stories. The finished image was a striking paradox: a blizzard of calligraphy in which every detail was perfectly visible: Peretz’s thick, drooping mustache, the deep bags under his eyes, his collar and tie, and his neatly coiffed hair.

My father had two objects of love—apart from his family—and he found a way to combine them: Yiddish literature and painting.

Tenenbaum went on to draw many more such portraits throughout his life, some in black and white, others in color. He created them for one reason only—as a homage to Yiddish and Hebrew writers he admired and loved. He received little recognition as an artist and refused on principle to sell any of his pictures. Art, he believed, was for the people. He donated his pictures to places where the writers’ spirits still lingered—Jewish schools, libraries, theaters and cultural centers, most of them in Buenos Aires.

A few of Guedale Tenenbaum's pictures ended up overseas, like the portrait of Leivck whose work frequently alluded to his early years as an anti-tsarist radical and his exile to Siberia. An artistic and technical triumph, the Leivick micrograph shows the poet gazing into the distance as if reflecting on the snow-covered jailhouse and the metal chains that bound him as a prisoner—both of which feature in the portrait. It is one of the most intricate and delicately colored micrographs we have ever seen, an unsung masterpiece hiding in plain sight.

Thanks to Avrohom Likhtenboym, director of the Buenos Aires Yiddish archive IWO, we managed to get in touch with Lía Tenenbaum, the artist's daughter. A retired optician living in Buenos Aires, she was only too happy to talk about her father. “My dad came across as a plain-speaking, brusque man,” she recalled, “but he was all heart. He used to read me children’s stories, in Yiddish of course. He was an extraordinary father with me, a great father, very dedicated.” Over many conversations by phone and later at her apartment, she tells us about her father, his struggles to afford ink, brushes, and sketchpads, his strong socialist convictions, and the values he inherited from his earliest years.

Guedale Tenenbaum (pronounced "Gedalia") was born in 1914 in Skidl, a majority-Jewish shtetl about twenty miles from Grodno. Then under Russian rule, it became part of independent Poland after WWI. His father was a tannery worker, a freethinker, and an educator who set up the first Jewish secular school in the town. At the age of thirteen, Tenenbaum left home to study in Vilna. His real passion was art, but he enrolled in a trade school and became increasingly active in radical politics. The Polish authorities began watching him, and in 1931 he fled the country, traveling by cargo boat to Buenos Aires. His father had already settled there, and his mother and two siblings soon joined them.

From his earliest days in Argentina, according to his daughter, Tenenbaum seems to have adopted the causes that would define his life—left-wing politics, Yiddish culture, and art:

My mother told me that when father was young, he was jailed for taking part in political rallies in Argentina. I remember when I was little that my parents were involved in supporting the left in the Spanish Civil War. Also, before I was born, my father worked for the IDRAMST (Yiddish Dramatic Studio), then the IFT (The Jewish People’s Theater), painting scenery for them. IFT was founded by factory workers who were also amateur actors; it was a political and ideological theater.

Tenenbaum married in 1934 and had two children: Lía first, then her brother Carlos. “We lived in two small rented rooms in a communal house in Villa Crespo [a Jewish workingclass neighborhood in Buenos Aires],” Lía remembers. “My brother and I slept on sofas in one room, and my parents slept in the other.” Tenenbaum was a weaver who devoted all his spare time to politics and culture. He was active in workers’ unions and channeled much of his energy into the ICUF (Idisher Cultur Farband, or Jewish Cultural Union), a Yiddish language organization with a thriving cultural life centered on the Peretz Club, of which Tenenbaum was the cultural secretary. He also wrote short stories in Yiddish and articles for the local Yiddish press.

Ever since his childhood in Skidl, Tenenbaum had loved drawing, sketching, and painting. In Buenos Aires he contributed illustrations for Yiddish books and, starting in the 1940s, began to experiment with the traditional Jewish folk art of micrography. Hundreds of years old, micrography started as a decorative element in Jewish ceremonial and religious art-a form of geometric patterning using lines of miniature handdrawn lettering. Torah scribes took it one step further: evoking the midrashic idea that text is the holiest part of creation, they began to draw poster-size portraits of famous rabbis and holy men using texts from their sermons and commentaries. Finally, this religious art was appropriated for secular and nationalist purposes. From the 1890s onward, portraits of prominent Zionists and leading Yiddish writers and playwrights were created for special occasions and sometimes reproduced as lithographic prints.

Tenenbaum was an avowed secularist, but he was drawn to this distinctive art form steeped in Jewish tradition and Yiddishkeit. According to his daughter, he cared passionately about making micrographs:

My father had two objects of love—apart from his family—and he found a way to combine them: Yiddish literature and painting. Just imagine—who spends their life making portraits of writers? The portraits were like his children. He adored making them.

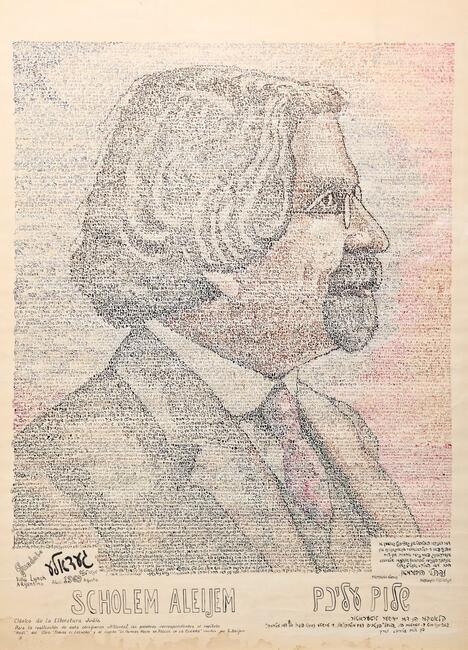

Tenenbaum's first micrographic portrait was of Pinye Katz, one of the most influential Argentine Yiddish literary figures. Editor-inchief of the long-running newspaper Di Presse, Katz was also a prolific translator, responsible for the first full Yiddish version of Don Quixote. Next, Tenenbaum completed an oversize micrograph of Chaim Zhitlovsky, renowned throughout the Yiddish-speaking world as a writer, philosopher, orator, and intellectual. Many other portraits followed, including Sholem Aleichem, Mendele, Peretz, and finally Leivick.

A kind of literary fabric or patchwork, its delicate colors are threaded through the picture like the warp and weft of a loom—a textile worker's text.

Tenenbaum approached his portraits as an artist-curator. Each one carries its own key, a kind of glossary to the portrait's formation. A later version of the Peretz portrait, for example, bears the date of its creation (May to August, 1971); a dedication (“In memory of my father, Peysekh Tenenbaum, 1887-1962, a Jewish working man who from his earliest youth fought for the ideals of social justice and equality”); a note about its recipients (“My comrades in the Belchatov Cooperative of Polish Jewish textile workers whose roots, like mine, lie in the activist traditions of the Jewish working masses”); and finally a list of ten poems and stories by Peretz from which the text is drawn. In this way, Peretz's own radicalism and sympathy for the anti-tsarist cause is yoked to the political and labor struggles of Tenenbaum's adopted homeland. That kind of duality is typical of Yiddish culture in Argentina. Rooted in Latin American soil, it reflected a deep engagement with the concerns and customs of its new environment. At the same time, it retained for decades a kind of shadow identity as a transplanted world of East European Jewry.

While most of his micrographs were in Yiddish, Tenenbaum also produced several in Hebrew and at least one in Spanish, a portrait of President Domingo Sarmiento. It's easy to see why Tenenbaum, a proud Argentine patriot, would have wanted to celebrate the liberal Sarmiento. But his principles led him to turn down another Spanish-language commission. Lía Tenenbaum remembers the episode vividly:

My father knew some supporters of President Juan Peron. They wanted to commission a portrait for some special occasion, maybe an anniversary. My father spent some time thinking how to refuse that offer. Of course it was dangerous to tell them the truth—that he didn't want to do it on political grounds. So he told them that he didn't know Spanish well enough! Of course that wasn't true—he read a lot in the language and he had already done the Sarmiento portrait by then.

Toward the end of his life, Tenenbaum began working for the Buenos Aires IWO as the curator of its art collection. The organization hosted two exhibitions of his work in 1976 and 1979 (as well as a posthumous one in 1990). He was still painting as intensively as ever, and in 1980 he made plans for his first visit back to Europe:

He had decided to travel to Denmark when he found out that his beloved teacher of Yiddish from the shtetl was still alive and living there. They had started writing to each other. He planned to go on to Israel; he had never been there and he wanted to see it. He also planned to take a micrograph to donate to Yad Vashem. When he was about to travel, he received a letter from kibbutz Ein Harod, telling him that their art museum would accept two of his paintings for their collection. I've never seen him so excited. He kept saying, “Lía, did I read you the letter?” And then, five minutes later, “Have I showed you the letter?” Then, suddenly, he complained about a chest pain and died of a severe heart attack. It was just six days before his trip. So really, he died from excitement. He was never ill. He was a very strong man.

Over four decades, Guedale Tenenbaum was responsible for perhaps the largest body of Yiddish literary micrographs created by a single artist. As such, his legacy should be secure. But time has not been kind to Tenenbaum's works. As the key institutions of Yiddish Buenos Aires-the Zhitlovsky School, the Bialystoker Farband, the Peretz Center—first faded, then closed their doors for good, many of the pictures he had donated were lost or thrown out. His portraits of Pinye Katz, Mendele, and others are long gone; the thick card of the imposing Zhitlovsky micrograph was ripped in two and thrown out, but an acquaintance of Lía's rescued the broken picture from an abandoned building and returned it to her.

The sad fate of these works reflects a broader story about the material heritage of Yiddish in Argentina and beyond. It's tragic that so many of Tenenbaum's remarkable portraits seem to have disappeared through sheer neglect. We should mourn their loss—and then celebrate those that have survived, like the extraordinary Leivick portrait. A kind of literary fabric or patchwork, its delicate colors are threaded through the picture like the warp and weft of a loom—a textile worker's text. It's a wonderful combination of freedom and precision, all of its elements perfectly in balance. Utterly distinctive, it confirms Tenenbaum's place as the last great Yiddish micrographer, the final link in a chain of portraitists born in Eastern Europe who repurposed a religious folk art to celebrate the heroes of a new literature.

David Mazower is co-editor of Pakn Treger and the Yiddish Book Center's bibliographer and editorial director. He writes about Yiddish theater and is a frequent contributor to the Digital Yiddish Theatre Project. Lila Fabro is Researcher in the Department of Performing Arts and Jewishness at the University of Buenos Aires.