MODICUT: The Madcap World of Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler

- Written by:

- Eddy Portnoy and David Mazower

- Published:

- Summer 2019 / 5779

- Part of issue number:

- 79

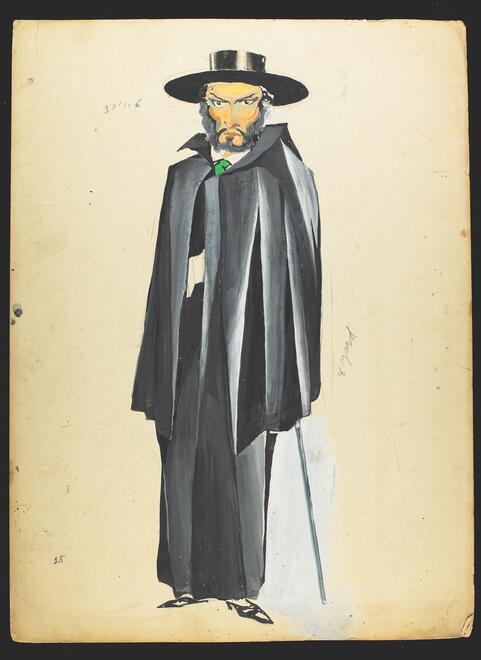

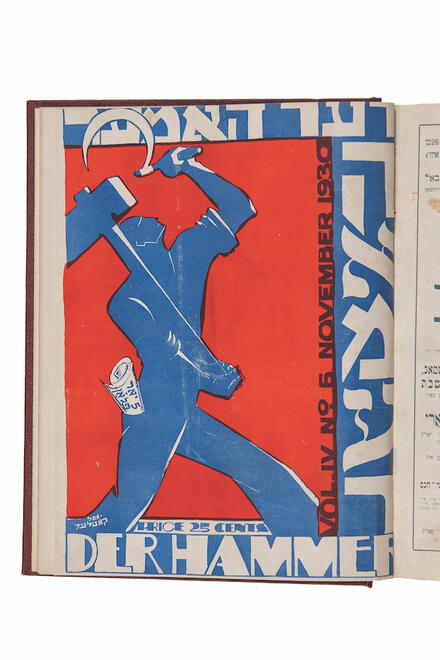

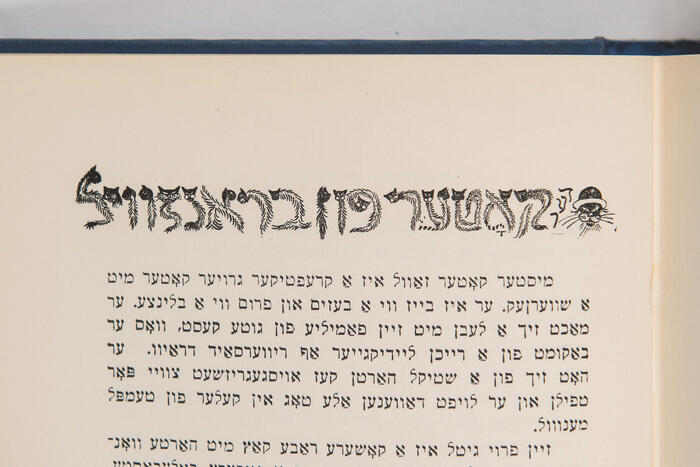

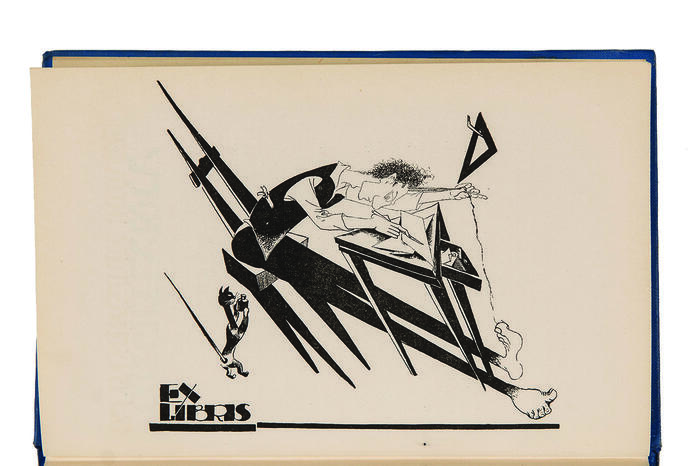

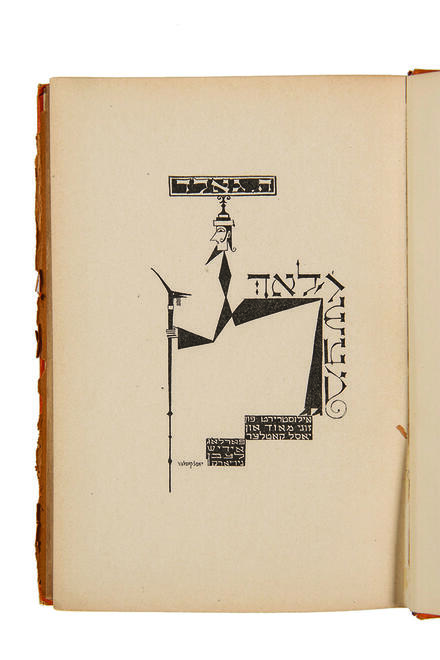

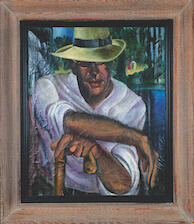

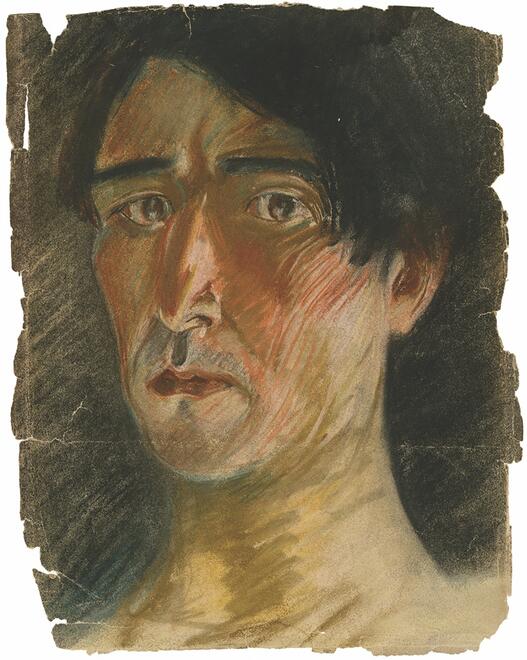

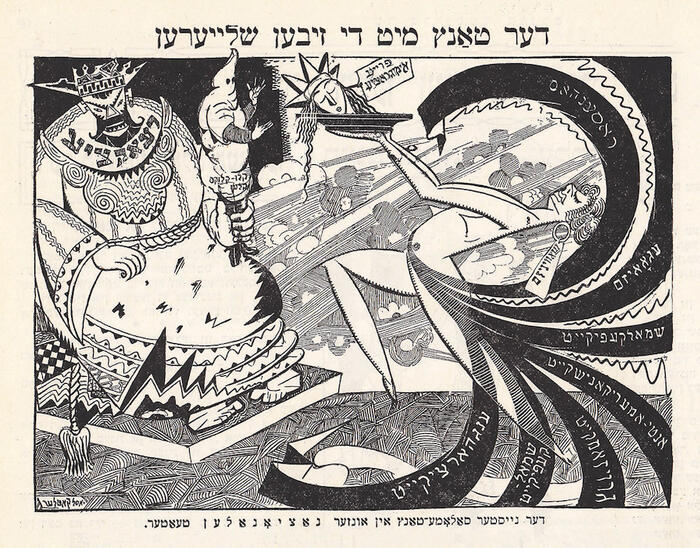

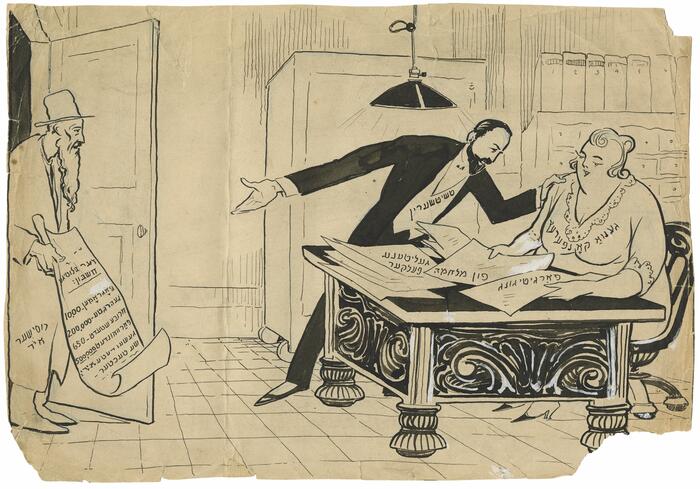

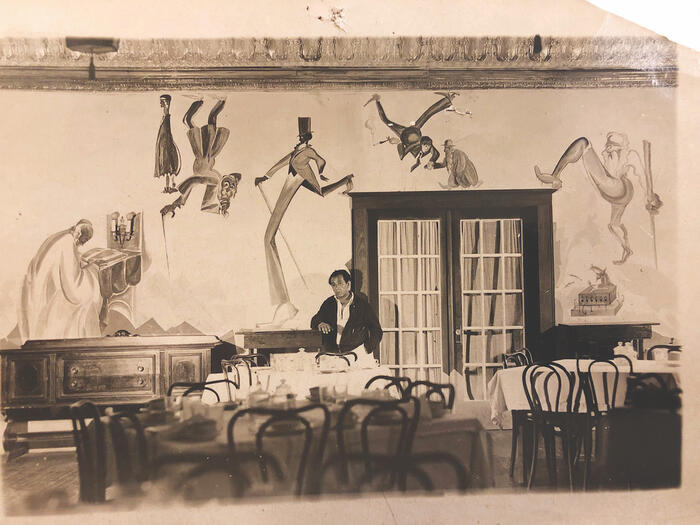

Functional surrealism isn’t a phrase often applied to Yiddish culture, but it doubtlessly suits the work of Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler, two artists active on the Yiddish cultural scene during the first half of the 20th century. Responsible for thousands of cartoons and book illustrations, surreal murals in Catskills summer resorts and literary cafés, and anarchic and hilarious puppet theater, Maud and Cutler produced some of the wildest, most unusual art that the Yiddish world had to offer.

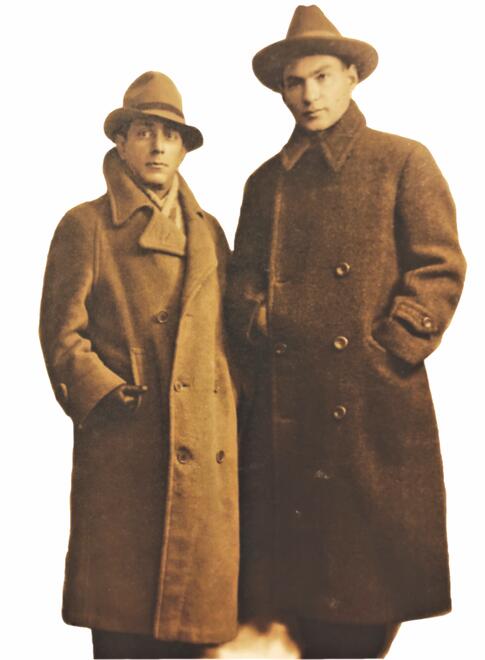

On the one hand, they worked incredibly well together. “Truly,” wrote the poet Melech Ravitch, “if there was anyone who ever doubted that a pair is prearranged in heaven, he should take a look at Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler. Such an artistic duo, each complementing the other so wonderfully, is truly a rarity in this world. Maud is short, Cutler is tall; Maud has a deep bass, a murky, dark bass, Cutler has a bright, cheeky, boyish tenor; Maud is full of Jewish folkloric tradition, Cutler is an expressionist—but when they’re together there is no contrast whatsoever.”

On the other hand, maybe they didn’t get along at all. “Cutler is the opposite of Maud. Maud is difficult, Cutler—easy. Maud is stubborn, Cutler—acquiescent. Maud is brutally critical, Cutler—naive and mild,” said Yiddish writer Noyekh Shteynbarg.

On the other hand, maybe they didn’t get along at all. “Cutler is the opposite of Maud. Maud is difficult, Cutler—easy. Maud is stubborn, Cutler—acquiescent. Maud is brutally critical, Cutler—naive and mild,” said Yiddish writer Noyekh Shteynbarg.

Maud, who arrived in New York in 1905 from Vaslikov, a shtetl near Bialystok, worked variously as an errand boy, a cigar roller, and in sweatshops before finding his way to the arts. Cutler, who hailed from Trostianets, a Ukrainian shtetl, appeared in New York in 1911 and found work as a sign painter before dabbling in literature. By 1907, Maud had connected with the literary group Di yunge and became their in-house illustrator. Cutler became the protégé of master satirist Moyshe Nadir, who brought him into the world of Yiddish letters.

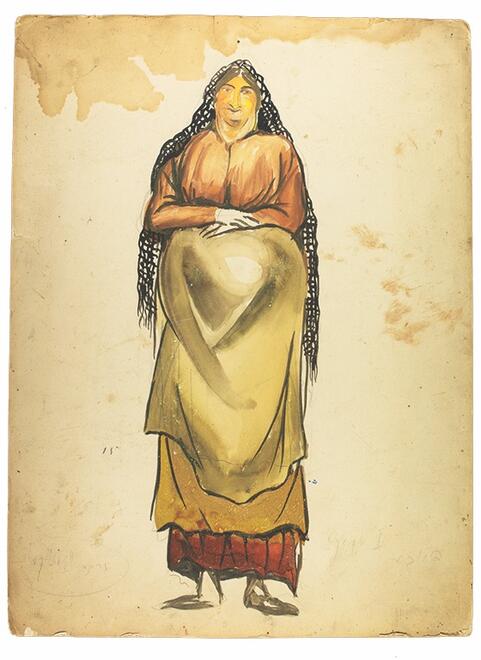

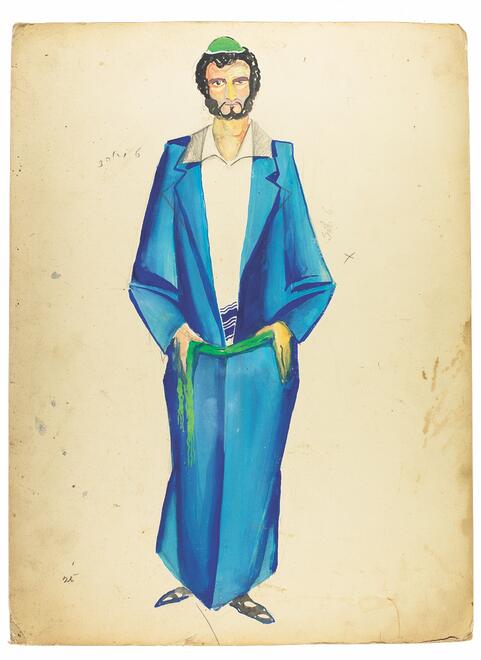

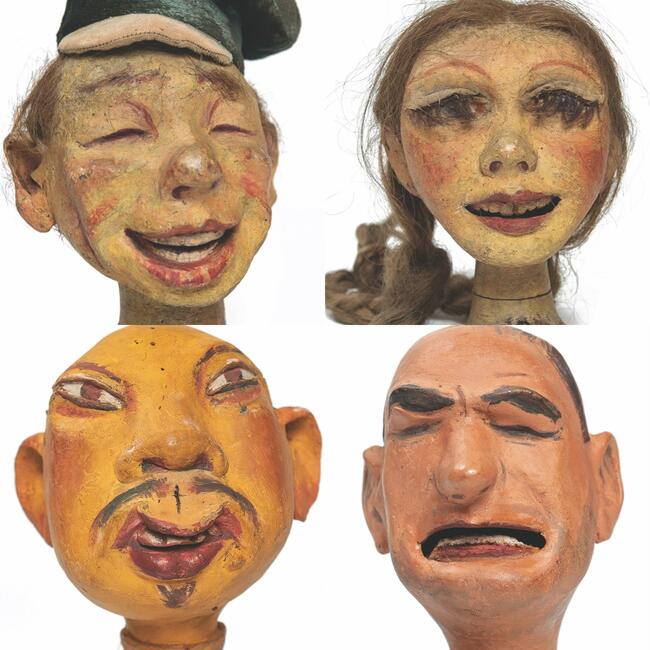

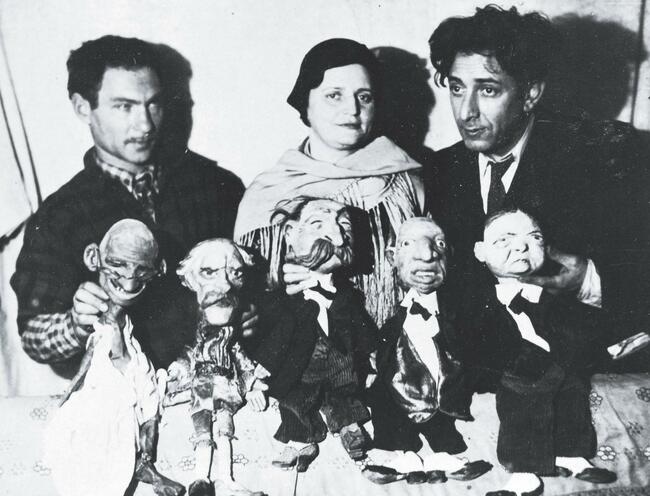

Having met in the early 1920s in the offices of the Yiddish satire magazine Der groyser kundes (The Big Stick), where they both worked as cartoonists, they quickly began collaborating on art projects, producing theater posters, costume and set designs, and selling painted furniture out of a studio on Union Square. In 1924, Yiddish Art Theater director Maurice Schwartz asked them to create some puppets for a scene in a new production of Di kishefmakherin (The Sorceress). They built the puppets, but Schwartz decided not to use them. Rejected, Maud and Cutler took their new creations to the literary cafés they frequented and did shtick. Someone suggested they start a Yiddish puppet theater.

With no experience running anything at all, they took the idea seriously and went back to their studio, where they created a bunch of “little Jews.” They wrote some scripts and rented an old clothing factory on 12th Street near 2nd Avenue that served as their first theater.

Performing parodies of classic Yiddish plays and of Jewish folklore, their theater, which they called Modicut, was a hit, selling out nine shows per week. Their puppets were their greatest success. They took them across the country and across the world—to Europe and the Soviet Union, where in 1932 they were asked to remain as heads of a Yiddish puppet theater collective. They demurred and returned to the United States, where they continued to perform to great acclaim, but not for long.

In 1933, they had a legendary fight, the source of which is still unknown. But it broke up the act. They each began to perform alone and with other partners, but never with the magic or the success they had when they were together. They continued, in their separate ways, to produce art—lots of art—for Yiddish periodicals and books until Cutler was killed by a drunk driver in 1935 and Maud by a heart attack in the mid-1950s.

Fusing Jewish tradition with an acidly satiric and surrealistic sensibility, Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler were responsible for some of the most original and unique art produced in the Yiddish universe. Opposites do attract—and then they sometimes explode.

“They were very close as artists but probably not personally. And my hypothesis about what they broke up over is just my hypothesis. You know, when the Soviet Union invited Zuni and Yosl to go over there, they brought along my aunt Bessie. She had been Zuni’s girlfriend, and when she got tuberculosis, Zuni asked his brother Zaydl for money so Bessie could go to New York for treatment. Zaydl said: ‘Sure I’ll give you money, but I want to marry Bessie.’ And so it happened. Zuni never married after that and never gave up his love for Bessie. Well, if three of you go to Europe, and it’s such a bizarre threesome, it was asking for trouble. I don’t know if Bessie had any ability as a puppeteer. She was just the good-looking woman. She was known as the Belle of Second Avenue." — Abe Rosman, Zuni’s nephew

“There was no art that Zuni didn’t do…. cartoons, painting, marionettes, wood carving, of course he made furniture and painted trompe l’oeil too, and wrote nonsense songs and poems...he was the total artist and whatever he did it was original—if he sewed a costume or made a piece of carpentry, it became a creative thing.” — Abe Rosman, Zuni’s nephew