The Yiddish Bohemians of Montparnasse

Introduction by David Mazower

- Written by:

- Chil Aronson

- Translated by:

- Ri Turner

- Published:

- Summer 2019 / 5779

- Part of issue number:

- 79

At the Yiddish Book Center, we call it the Big Green Book. Bilder un geshtaltn fun monparnas (Scenes and Figures of Montparnasse) is a monumental tome, about the size of a small suitcase. The work of a Polish Jewish art critic named Chil Aronson, it offers a unique perspective on the École de Paris—the extraordinary constellation of Jewish artists who flocked to Paris in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Aronson was an established art critic for the Polish Yiddish press by the time he moved to Paris in 1927. Captivated by the émigré art scene in Montparnasse, he became its devoted chronicler. A gregarious and popular figure, he visited painters in their studios and homes, gossiped with them in cafés, and reviewed their exhibitions.

There is a vast literature on Soutine, Chagall, Kisling, Ryback, and their ilk—but there’s nothing quite like Bilder un geshtaltn. In the course of seven hundred oversize pages, a glorious panorama of bohemian Paris unfolds before us—its cafés and characters, literary banquets, gallerists, painters, and models. There’s something almost Proustian about Aronson’s elegiac and detail-laden re-creation of a vanished world. His voice is by turns gossipy and analytical—he had both the curiosity of a tabloid journalist and the mind of a scholar. But above all, this is a portrait of Montparnasse as a Jewish cultural space. Aronson’s Yiddish lens brings into sharp focus the common bonds of language and identity that linked Yiddish-speaking artists and writers, even as they moved in other, overlapping circles—French, Russian, or Polish.

How ironic that this memorial to a bygone era should itself have vanished into almost total obscurity in the half century since its publication in 1963. Never translated, it remains inaccessible to most art historians. We hope these brief excerpts prompt renewed interest in Aronson and his forgotten classic.

—David Mazower

The Bookstore Le Triangle and Café Daumesnil

It is impossible to describe Montparnasse as it once was without mentioning the famous Triangle Press and Bookstore, which was located on the small street Rue Stanislas, number 6. The bookshop consisted of one long, narrow room and a second, darker room, which served as a stockroom. The proprietor was a small, dynamic, extremely hospitable man with dark hair. This was Kiveliovitch, formerly a student of the famous French mathematician Hadamard. Professor Kiveliovitch himself was one of the greatest mathematicians in France. At the same desk in the bookstore where he did his accounts, he also solved deep mathematical problems.

One morning, I came into the bookshop and saw that Kiveliovitch was beaming. “I see you’ve just landed a good deal,” I said to him. But Kiveliovitch answered, “Guess what—I’ve been trying to solve a certain important mathematical problem for quite a long time. I finally solved it yesterday evening, and I’m so happy.” He looked like a man who had been carrying a heavy burden on his shoulders for a long time and had finally set it down . . .

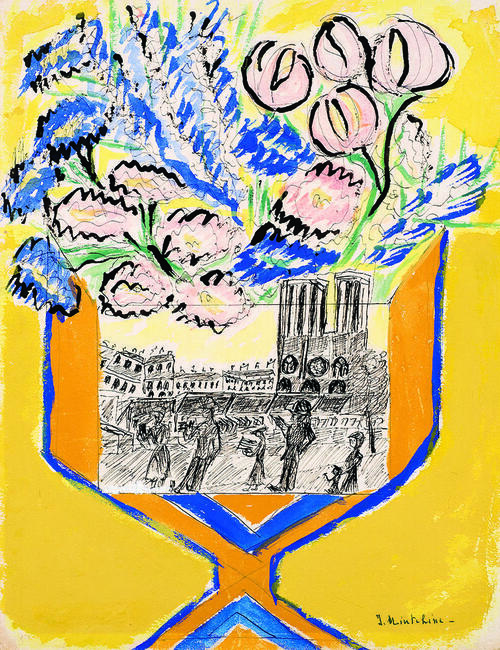

I first visited the Triangle Bookstore (its name hinted at its proprietor’s profession) when I moved to Paris and settled in the neighborhood of Montparnasse. Around that time, Triangle had begun to publish a series of short booklets about famous Jewish artists, illustrated with numerous reproductions. Each booklet cost only one franc, and they were written by well-known French art critics for a Jewish readership. Because the Triangle Press was in the process of publishing these booklets, the well-known Jewish artists of Montparnasse often showed up in the bookshop: Jacques Loutchansky, Adolf Feder, Leopold Gottlieb, Moïse Kisling, Pinchus Kremegne, Jacques Lipchitz, Mark Chagall, Abraham Mintchine, and others. Almost all the Yiddish writers who frequented the artist cafés of Montparnasse were also Triangle regulars. They included Sholem Asch, Oyzer Varshavski, and Joseph Milbauer, as well as the renowned Soviet painter Nathan Altman, the chemist Meyer Mendelson, and others. Joseph Opatoshu also used to come into the bookshop whenever he visited Paris.

The Triangle was also a hub for the latest gossip about Jewish artists in Montparnasse. For example, the Poale Zion activist Y. Nayman ran into the Triangle one day, barely able to catch his breath. He said he had happened to visit the Basilica Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre on a Sunday and he had seen the talented Jewish sculptor Marek Szwarc among those kneeling in prayer. In short—the latter had gone astray. This rumor was later confirmed. Kiveliovitch was also the first to suggest that literary evenings be organized at Café Daumesnil. These were extremely successful and well-attended by young Jewish immigrants from the Old Country, who brought with them a longing for warm, Polish yidishkayt in cold, foreign Paris.

In 1929, the famous Moscow Yiddish Art Theater, directed by Alexander Granowsky and starring Solomon Mikhoels, came on tour to the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin. They played to packed halls, with Mikhoels’s talent a particular cause for admiration. It is no wonder that when Mikhoels was invited to give a lecture about spoken Yiddish in Café Daumesnil, more people came to hear the master of the Yiddish stage than could fit into the room. With his wonderful mimicry and diction, Mikhoels demonstrated how the Yiddish language could take on various meanings in the mouth of a Jew from a previous generation.

A fine banquet was also held in Café Daumesnil in honor of the Yiddish writer Avrom Reisen. Sholem Asch, Zalmen Shneur, Dovid Einhorn, and I myself addressed the gathering. The guest responded with a deeply moving speech. It was truly one of the loveliest literary banquets in Paris. Today, whenever I walk past the Café Daumesnil, where an eerie silence reigns, I remember the magnificent Yiddish evenings we used to have there and the enthusiastic attendees, of whom so many were torn from us by the devastations of the Holocaust.

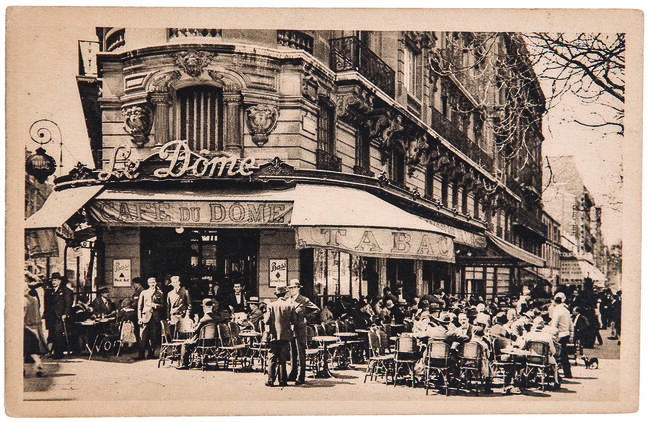

Sholem Asch at the Café du Dôme

I first met our great Yiddish writer Sholem Asch in 1925, two years before I arrived in Paris. It was during one of his regular visits to Warsaw, when he used to take the Yiddish Writers’ Union at Tłomackie 13 by storm, sending tremors through the Yiddish literary world. The next time I saw Sholem Asch was in Paris, on the terrace of the Café du Dôme. He visited the café often. I can still picture his tall, stately figure and his thick black head of hair. He seethed with energy, joie de vivre, and creative power.

When I observed him, I noticed that his searching gaze didn’t miss a single figure who appeared on the terrace. When a young, beautiful woman floated by, he cast an appraising look from her head to her toes. He took a powerful, sensual pleasure in life, and he was a phenomenal intellectual laborer, who often spent months at a time chained to his writing desk when a new novel was taking shape in his imagination.

He took a powerful, sensual pleasure in life, and he was a phenomenal intellectual laborer, who often spent months at a time chained to his writing desk when a new novel was taking shape in his imagination.

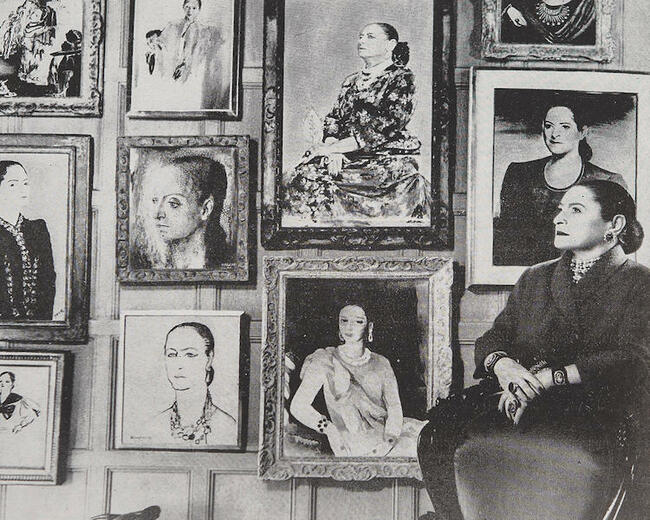

Asch was also a passionate collector of Judaica. In Paris he knew a whole world of antique dealers and flea markets that he loved to visit after his working hours. By then he had settled into a private villa in Bellevue, not far from Paris. I visited him there a few times. The cozy dining room held several glass-fronted cabinets packed with antique Judaica. Asch invited me to appraise his art collection because, he said, his wife thought he was “wasting” money on it. In fact, it was quite the opposite: his wife knew that her Sholem bought his paintings for half of what they were worth.

On the walls of his living room, I saw gorgeous paintings by Kisling, Kremegne, Eugene Zak, Zygmunt Menkes, Raymond Kanelba, Jules Pascin, Isaac Levitan, and others. I was surprised not to see anything by Chagall. It turned out that Sholem Asch had suffered a small defeat on that front. At that time, Marc Chagall lived in Boulogne, in a nice villa hung with his exquisite masterpieces. Sholem Asch had chosen one of the most beautiful works and begun to bargain. As was his habit, he tried to convince Chagall that once the painting was hanging in his study, it would inspire him to write great works of literature for the Jewish people, and therefore he had to have the painting. However, Marc Chagall was utterly unmoved by this argument and demanded to be paid in full for his masterpiece. As an alternative, he suggested selecting several pieces out of Sholem Asch’s collection of antique Judaica. Chagall knew what he was doing—and ultimately nothing came of the deal.

Bella Chagall—Craftswoman of the Yiddish Word

The first time I saw Bella Chagall was during my first visit to Marc Chagall in 1927, in his villa at 5 Allée des Pins in Boulogne. It was a hot summer day, and we sat in the little garden around a small, round metal table. We spoke about Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, and also Charlie Chaplin, about whom Chagall always had original things to say, which I now greatly regret not having noted down. Bella invited me to come over more often.

As I walked home from my visit to Chagall—down the wide Boulevard de Boulogne—I tried to put together what I knew about Bella. I knew that she came from a wealthy family of Lubavitcher Hasidim, but she had graduated from a gymnasium and studied in the department of literature at Moscow University. Like all Jewish women who went to university, she must have been a revolutionary, I thought, and she probably knows Pushkin, Lermontov, Blok, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov, Gorky, and Leonid Andreyev by heart. At that time, it didn’t occur to me that she could love our classic Yiddish authors just as much, especially Sholem Aleichem.

At the end of 1941, I saw Bella and Marc Chagall on the terrace of Café Savoy in Nice before they left for America. The sea lay spread before us, and its shimmering radiance upset me—my heart was heavy to begin with. I took my leave of Bella and Marc Chagall, hoping that we would meet again in Paris soon after the war.

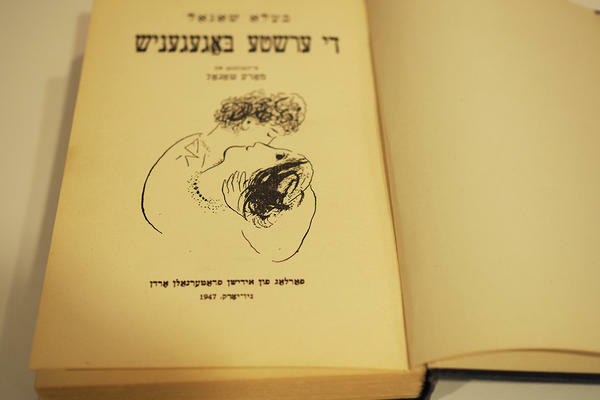

After the Liberation, I remained in Nice for a few months. One day I opened a French newspaper and found Marc Chagall’s congratulatory message to France on the occasion of the Liberation. In the same newspaper, I read with an aching heart the news that Bella had passed away at the age of 49. When I met Marc Chagall in Paris later, he gave me Bella’s two books: Brenendike likht and Di ershte bagegenish. Those two books were a real revelation for me. I never imagined that Bella possessed such a rich, juicy Yiddish or that she was such a mature, evocative craftswoman of the Yiddish word.

The Glory and Decline of La Rotonde

Between 1910 and 1914, the Café de La Rotonde served as the primary home for the best Montparnasse artists, whether French or foreign. Why did they select La Rotonde as their main hangout? Undoubtedly because of the café’s proprietor, Herr Libion, who was a true friend to all artists. He wanted them to feel at home in his café and instructed his waiters never to interfere with the artists’ long discussions. In winter, when it was cold in their unheated ateliers, the artists came to La Rotonde to sit for long hours undisturbed over a café crème.

Among the various female models who posed for the Montparnasse artists and whom I noticed at La Rotonde, the creole Aicha made a strong impression on me. She was said to be the daughter of a Negro prince from Africa. She was small, slender, and graceful, like a bronze sculpture hammered out by a master. She posed for a large number of painters and sculptors.

In the Rotonde I became acquainted with the painter Granovsky, known as “the cowboy.” He was one of the artists who had come from Eastern Europe before the First World War. In 1914 he had enlisted in the Foreign Legion and distinguished himself on the battlefield. When I think of him now, I see him in his cowboy uniform, with a wide hat and a checkered shirt. Always smiling, always optimistic, he looked like an old-fashioned Jewish tradesman. I never found out why he dressed like a cowboy. He was one of the most popular figures in Montparnasse, but he rarely sold a painting. In order to earn a living, he worked as a house-painter. He’d greet me warmly from across the room. “Bonjour, Aron! Ca va?” During the German occupation, he was taken from his home and deported. Perhaps he thought that Pétain’s mob would treat him well because he had fought at the front on behalf of France. My memories of La Rotonde are always bound up with Granovsky, the vanished cowboy.

Mané-Katz, the Romanticist of Jewish Religious Life

More than twenty-five years have passed since I first met Mané-Katz on the terrace of the Café du Dôme. Throughout that time he has barely changed: the same small, lively figure that never stays still, the same blue eyes in the same affable, smiling face. Only his thick hair has turned white.

I visited him several times in his previous studio, off an old alleyway in a working-class neighborhood, at 18 Rue du Moulin-de-Beurre. And when he moved to a new studio on Boulevard Raspail, I began to visit him frequently. He had the most original setup of any artist I knew in Paris. His room was packed with old gold-embroidered velvet curtains made to conceal Torahs, rich Jewish fabrics, brocades, brass chandeliers, spice boxes, silver Torah crowns, beautiful tin Seder plates, and other rare pieces of antique Judaica, which coexisted peacefully with old Roman and Gothic stone and wooden sculptures. It is as if he had brought a piece of his childhood synagogue with him into his studio on Parisian soil. Even after so many years in Paris, Mané-Katz, one of the most popular artists, hid within his soul a mysterious longing for the Old Country, which is evident from his paintings.

Art critic and author Chil Aronson (also known as Chil Aron) was born in Poland around 1896 and died in Paris in 1966. He wrote extensively on modern art in Yiddish, Polish and French.

Thanks to Natalia Krynicka and the Bibliothèque Medem in Paris for providing information about Chil Aronson from the Yiddish Press.