A Good Friend in Troubled Times

With a Translator Profile by Alisa Solomon

- Written by:

- Rokhl Faygnberg

- Translated by:

- Elissa Bemporad

- Published:

- Fall 2019 / 5780

- Part of issue number:

- 80

Translator Profile: Elissa Bemporad

Edited from print version

[. . .] Though [Rokhl] Faygnberg was a prolific writer in multiple genres—novels, short stories, reportage, essays, a play—she has fallen into obscurity like most women who wrote in Yiddish in the early twentieth century. Many of them have been neglected because, as Anita Norich has argued, they mostly wrote for periodicals; their fiction was serialized in newspapers rather than published in the more permanent form of books, a gender inequity at the source. But Faygnberg did publish books, and [translator Elissa Bemporad] wonders if, on top of just plain old sexism, Faygnberg’s ardent shift to Hebrew when she settled permanently in Palestine in 1933 also led Yiddishists to neglect her.

Faygnberg wrote with particular sensitivity to women’s emotional lives. For instance, her novel Af fremde vegen (On Foreign Paths, 1925), traces the extramarital affair between a beautiful, bristling young woman and a married man against the backdrop of a modernizing shtetl. Capturing the inner anguish of the heroine, Faygnberg tacitly mounts a scathing critique of the sexual double standard.

In the passage Bemporad translates here, from a festschrift (collection of essays) celebrating the influential Yiddish editor and writer Mordkhe Spektor, she extols the soup ladle, the emblematic tool of a housewife’s many chores. Bemporad reads irony in Faygnberg’s cheery words. After all, Faygnberg had published a number of works by the time she penned this remembrance in the late 1920s, a good while after the end of her five-year marriage to a man 25 years her senior—the only period in Faygnberg’s life when she didn’t write at all. [. . .]

— Alisa Solomon

ALISA SOLOMON teaches at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, where she directs the Arts & Culture concentration in the MA program. A theater critic and general reporter for the Village Voice from 1983 to 2004, she has also contributed to the New York Times, The Nation, NewYorker.com, Tablet, the Forward, Howlround.com, killingthebuddha.com, American Theater, TDR—The Drama Review, and other publications. Her first book, Re-Dressing the Canon: Essays on Theater and Gender, won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism.

A Good Friend in Troubled Times

By Rokhl Faygnberg, translated by Elissa Bemporad

Born in 1885 in the town of Lyuban, Rokhl Faygnberg received a rich and varied education as a child and, under the influence of popular novelist Shomer, wrote her first novel at age thirteen. Following the deaths of both her parents and two older brothers, Faygnberg moved first to Odessa, and later St. Petersburg and Lausanne, where she continued to further her literary career. In 1933 she moved to Palestine, where she continued to write in both Yiddish and Hebrew, becoming a major literary and journalistic figure in both languages.

I met Spektor again in 1916. He was living in Odessa, while I was living in a nearby shtetl on the road that leads to Balta. At the time, my family responsibilities kept me away from literature and literary circles. While only personal matters brought me back to Odessa, I could not keep away from Spektor. Something always drew me to stop by and check in on him, to simply pay him a visit, as one would do with a close acquaintance, or just with a fine person. On one afternoon I took advantage of the opportunity and came by his home. I saw the same friendly and jovial Spektor.

He lived on Yekaterina Street, in the same building as the Yiddish teacher and community leader Glazer-Dzabin. His room was very bright, draped in sunshine, and every corner was filled with the comfortable adorned domesticity that Berta Spektor was so keen on in her commitment to order and beauty. I bragged to him right away about my small-town accomplishment. “And now, Mr. Spektor, try to reproach me. I have, thank God, found a purpose. . . I have finally become a housewife like any other.”

"And now, Mr. Spektor, try to reproach me, I have found a purpose. . . I have finally become a housewife. . ."

This brought tears to his eyes. “Really? Really?” he uttered, suddenly happy. “A perfect housewife, a real housewife! With your own house in a small town, with a whitewashed porch, with trees under the windows, and maybe even with a well in the court-yard, and with a white tablecloth on the Sabbath, candlesticks on the table, a large stuffed carp, and a cheesecake . . . Very good, very good, Rokhle, but are you sure you can really be a housewife? The work of a housewife actually functions like a machine. If the mechanic in charge works well, then the machine also works well, in a timely fashion just like a clock; but if the mechanic is a ne’er-do-well, then the whole machine is good for nothing.”

But again I boasted of my housekeeping knowledge, and with great precision reported to Mrs. Spektor how I cooked and baked, and how I taught my crude peasant servants to do the laundry according to my cultured city method. While Spektor listened and danced with joy, Berta suddenly confronted me with a hard question. “So did you actually get rid of your pen entirely and give up writing?”

“The pen? I traded my pen for the soup ladle!”

Spektor became excited: “Why do you make so much fun of the soup ladle? There will soon come a time when the soup ladle will take over the world. It will take a place of honor, like a jewel, while the disfavored pen will have to hide in a corner. Oh, and the soup ladle will still speak words. And the pen? Who needs the pen now? A bargain!” He was so agitated that we barely managed to calm him down. And then I bid him farewell lovingly, but only after he promised me that he would come and visit me together with Berta during the holiday of Sukkes: he would then see how seriously and with what degree of erudition I relate to the soup ladle.

It was time for me to go, but as I left the courtyard, he called me back from the balcony. I headed back and started up the stairs. Spektor was waiting for me by the door, with his cape over the shoulders.

“What’s the matter, Mr. Spektor, we did not part properly?”

He smiled affectionately. “It’s not that important. I just remembered that we publish a literary collection here. Would you happen to have written something of the length of three hundred lines?”

“Apparently, the wolf always lures the prey into the depth of the forest,” I said as I laughed my heart out. “It means then that a pen can still be useful to someone.”

Once again Spektor smiled warmly. “We writers still need it. It is irrational, like all irrational things. It is their fault,” he suddenly began to defend himself, “the youngsters here, the young khevre, who out of the blue decided they wanted to put together a collection and dragged me into this affair. I really think that you should write a contribution of some three hundred lines . . .”

"But Mr. Spektor, what kind of writer am I now?"

“But my dear Mr. Spektor, what kind of writer am I now? How can I now find the time for such things? The Jewish holidays are almost here, then I have to prepare some food for the winter, I need to marinate the squash, pickle the tomatoes, cook the preserves and jams . . ."

“Wonderful,” he suddenly realized cheerfully.

“This is perfect! Describe for me how you cook jam. Just write a story of how a small-town housewife like you, here, near Odessa, prepares for the winter at home.”

I promised him I would write my housewife story, and he gave me his blessing for the road. But nothing came of it. The extraordinary events of those years plunged Ukraine into a vortex of destruction and death, and once again we lost sight of each other.

It happened during the fall of 1919. After the dreadful summer of the Jewish massacres, when I went into hiding among the peasants of the nearby villages holding my child in my arms, I eventually reached Odessa. I went to see Spektor at once and told him about my Ukrainian scroll of agony, about my fine small-town home with the acacia trees below its windows, which was destroyed. I told him how I managed to reach the city at the risk of death, of how a good-hearted Bulgarian peasant gave me her holiday dress with the national colors for the journey, and how I put a little cross around my child’s neck: not only were Jew-murderers still roaming the Balta roads, but signposts by General Grigoriev were still hanging from the telephone poles, calling on people to kill all little Jewish boys, because when they grow up they will all be communists. He listened to everything I said without making a sound. Then he invited me into the building of the Odessa Jewish community so that I could hear the stories of the Uman refugees, about how entire families were buried alive, so that I would soon forget about my own trivial problems. “But bring with you a notebook and pencil,” he added, “everything, everything must be recorded.”

From then on, every day, we used to stop by the kehile (community) building and hear out the stories of the refugees of the Ukrainian Jewish khurbn, the destruction period. There were several writers among us there. Jews would tell us their stories and we would write them down, and then we would discuss the terrifying details that had been conveyed to us, which caused our blood to freeze in our veins. Later some of us began to revise the collected materials in the form of short stories. At the time all of us, together with Spektor, already worked for the cooperative publishing house Daat, where we translated hundreds of short books for the Yiddish “universal library.” One time, as we were sitting with Spektor in the press’s editorial office, one of our friends read out loud for us a pogrom short story, in which he described how a Jewish Red Army soldier killed a village peasant woman who had just given birth, together with her newborn child, as an act of revenge for his murdered father. Spektor flew into a rage, and infuriated, he began at once to tell the writer to remove this description from his story. “It’s actually a lie!” he pleaded with the writer. “That a Jewish soldier should kill a woman who had just given birth with her newborn! No, it’s a lie! Remove this passage this very instant! We cannot publish it as it is. Do you hear me? Leave that pleasure to them! Let them torture and kill women who just gave birth with their newborns. Have you ever heard of such an idea? That’s an idea that gentiles have!” The author of the short story heeded his plea and deleted from his notebook the passage with the murdered peasant woman and her child. Spektor calmed down. And as he walked home, he smiled and said, “What do you say? We just snatched from the jaws of death two innocent souls . . . ”

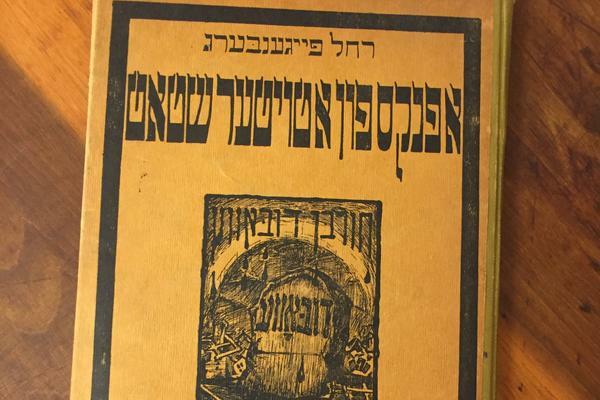

This excerpt is taken from the Spektor bukh, a volume of essays published in Warsaw in 1929, four years after Mordkhe Spektor’s death. Faygnberg’s memoir, Spektor der privat-mentsh (The Private Mordke Spektor) can be found between pages 124–141 of the volume. Our excerpt is taken from two parts of the original essay: the first can be found on pages 126–9, the second on pages 132–3.