The Sun Never Sets on the Vilna Troupe

- Written by:

- Debra Caplan

- Published:

- Summer 2014 / 5774

- Part of issue number:

- 69

An international entertainment conglomerate renowned across five continents for its high-quality productions. Performers who tour up to sixty cities a year, crossing national and continental borders with ease. Actors who are beloved around the world, regardless of the spectators’ native language. An iconic brand instantly recognizable by audiences across the globe because of its distinctive style, repertoire, and logo.

Is this Disney? Cirque du Soleil? The next viral Internet sensation? None of the above. In fact, I’m describing a theatrical entity founded nearly a century ago by a motley group of teenaged amateur performers, Jewish war refugees, and out-of-work Russian actors of Jewish descent who banded together to revolutionize the Yiddish stage in German-occupied Vilna during the First World War. Subsisting on rations of a single boiled potato per day and routinely fainting from hunger during rehearsals, the actors nevertheless proclaimed that their company heralded the dawn of a new era in which high-art ideals and “literary” drama would replace what they saw as Yiddish theater’s overly commercial leanings and melodramatic fare.

The Vilna Troupe actors were by no means the first Jewish performers to demand a higher artistic standard from the Yiddish stage, but they were the first to demonstrate that such an approach could also bring commercial success. Over the next twenty years, the Vilna Troupe continued to amass unlikely success stories: German military commanders invited the company to move from a leaky, decrepit former circus building to the finest theater in all of Vilna, a venue that had never before permitted Jews upon its stage. In a bold stroke of innovative interpretation, the troupe produced an “impossible” play that dozens of other theater companies had refused to stage; it became an instant sensation (today, The Dybbuk is still the most well-known and frequently produced drama of the Yiddish repertoire). Royal command performances were requested by the rulers of European nations. The troupe received fan mail from major figures like David Belasco, George Bernard Shaw, Harold Clurman, Albert Einstein, and Sarah Bernhardt. The plucky band of performers succeeded, in front of Jewish and non-Jewish audiences alike, on a scale unprecedented for a Yiddish theater company—before or since.

The Vilna Troupe was also more resolutely global than any Yiddish theater company had been before, and I believe it was this factor, combined with the company’s conception of itself as a world-class ensemble, that enabled the Vilna Troupe’s remarkable success. As Vilna Troupe actor Joseph Buloff used to say, at the height of his career “the sun never set on the Yiddish stage.

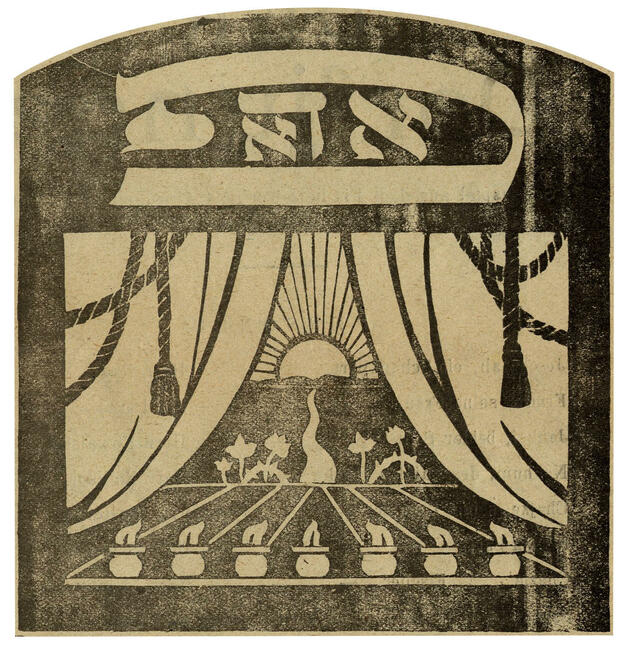

The Vilna Troupe, however, was actually not the single theater company it appeared to be on the surface but rather a constellation of multiple companies and hundreds of individual actors performing simultaneously under the same brand name. From its beginning with an actors’ quarrel over a love triangle in 1918, there were always multiple Vilna Troupes operating at the same time in different locales, all performing a virtually identical repertoire and all advertising their performances with the same iconic Vilna Troupe logo. In public, each Vilna Troupe vehemently denied the existence of all of the others; privately, however, actors and directors routinely migrated between various branches of the company in order to resolve interpersonal quarrels or to negotiate better paychecks.

The company began in 1915 as a group of some fifteen young actors, but twenty years later the Vilna Troupe was a global Yiddish cultural institution that included about 250 actors performing simultaneously across Eastern and Western Europe, North and South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Australia. Sometimes actors formally organized into discrete Vilna Troupe branches (there were at least seven between 1915 and 1935); other times, individual actors simply performed material from the Vilna Troupe repertoire, employed the logo, and advertised their shows as “Featuring __________ of the world-famous Vilna Troupe!” It was no wonder that spectators and critics alike were confused about who, what, or where the famous “Vilna Troupe” actually was at any given moment. In fact, the Vilna Troupe was everywhere that Yiddish theater was performed, and it included within its ranks nearly every major figure of the interwar Yiddish theater: Zygmunt and Yonas Turkow, Boris Aronson, Jacob Ben-Ami, Moyshe Broderzon, Rokhl Holtzer, Ida Kaminska, Henekh Kon, Mikhl Weichert, Avrom Morevsky, Jacob Rotbaum, and hundreds of others.

Individually, the nomadic actors of the Vilna Troupe often longed for a more stable home. But collectively, it was precisely the company’s persistent itinerancy that enabled the Vilna Troupe to thrive for twenty years and to develop a loyal global following. Each successful production by one branch of the Vilna Troupe only enhanced the reputation of the others. Any actor who could claim an affiliation with the Vilna Troupe could almost instantaneously attract a large audience almost anywhere in the Yiddish-speaking world. Crossing borders as a matter of course, the members of the Vilna Troupe encountered new theatrical techniques and repertoire from other theater artists around the world, then adapted these globally sourced models into their own productions. For example, the Vilna Troupe was the first to introduce black box theater to Poland; a few years later, the company also presented the first-ever Eastern European production of a Eugene O’Neill play (Desire Under the Elms, in the troupe’s own Yiddish translation). In this way, the Vilna Troupe exerted tremendous influence on dramatic repertoire and experimental theater techniques across the globe.

Debra Caplan began learning Yiddish in 2004 as an intern at the Yiddish Book Center and went on to earn her doctorate in Yiddish from Harvard. She is assistant professor of theater at Baruch College and City University of New York. Her articles have appeared in American Theatre Magazine, Comparative Drama, New England Theatre Journal, Theatre Survey, and Modern Drama. She is the cofounder, with Joel Berkowitz, of the Digital Yiddish Theater Project and is writing a book about the Vilna Troupe.