On the Trail of The Salamander

Isaac Bashevis Singer’s first literary venture was lost for almost a century—until a partial copy resurfaced in an attic in Poland.

- Written by:

- Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska

- Published:

- Summer 2018 / 5778

- Part of issue number:

- 77

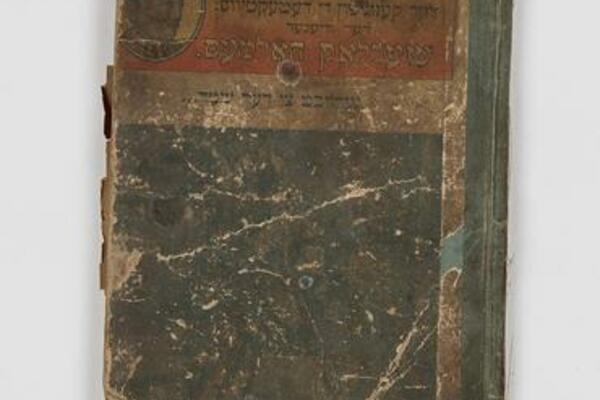

Some months ago a thin parcel arrived at the Yiddish Book Center postmarked Lublin, Poland. Inside were a few stiff sheets of yellowing card. Crinkled and mottled, they looked and felt like oversized Passover matzos. On one side, deeply imprinted, were four-square layouts of Tehillim, the Hebrew psalms, and pages from the siddur, the standard Jewish prayer book. On the other: double-page proofs in Yiddish. It was an extraordinary feeling to see and hold them, knowing the saga of their survival. Dating from the 1920s, they had outlived bombing raids, fires, and the murder of almost everyone whose hands had ever touched them.

The sheets from Poland were the biggest clues in a mystery worthy of Bashevis himself—the complete disappearance of the literary journal he edited as a young man, barely out of his teens. Salamandrye (Salamander) is the holy grail of Singer scholarship. No library in the world has a copy. Not a single one appears to have survived. It is as if the young Singer had devised the perfect vanishing act—a mythical journal named after a creature with supposed supernatural powers.

A few years ago, however, the story took an extraordinary turn. A cache of old printers’ proofs turned up in Bilgoraj, the Polish town where Singer was living when he edited the journal. The proofs found their way to Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska, Poland’s leading Singer scholar. She saw the name Salamandrye on one of the sheets and immediately recognized their significance.

On the following pages, Professor Adamczyk-Garbowska finds traces of the mature Singer’s genius in his first literary venture. And you’ll find three Pakn Treger exclusives: translated excerpts from Singer’s earliest writings; new details of his ties to a renowned family of printers; and full-size reproductions of some Salamandrye page proofs, exactly as they resurfaced in Bilgoraj.

A Writer Is Born

Of all the places in which a long-lost Singer work might be found, the small Polish town of Bilgoraj would surely seem one of the least likely. Not only is it many decades since Singer lived there, but almost the entire town was burned to the ground during World War II.

And yet there’s something fitting about the chance discovery in a Bilgoraj attic. Helped by Jews with family roots there, the town has been reconnecting with its pre-War past and celebrating the writer whose stories spread its name around the world.

In May 2003, I helped organize a Bashevis Singer festival in Bilgoraj, where the writer lived as a teenager. It aroused interest in his work as well as that of his brother I. J. Singer and his sister Esther Kreitman. The following spring a remarkable discovery was made in the attic of a dilapidated house in the town—several dozen sheets of recycled, printed paper from the former Jewish printing house of N. N. Kronenberg. I received them from the director of the Bilgoraj museum and saw that they were pages from the long-lost Salamandrye, together with various other publications.

On the basis of the preserved pages it is possible to reconstruct about half of the periodical. Salamandrye appears to have contained thirty-two pages. On the title page we find the journal described as the first issue of an occasional anthology, edited by “Itche Zinger” and issued by him together with “Y. Sh. A. Kronenberg.” In the mold of the many modernist Yiddish journals produced at that time, it contains prose, poetry, and essays.

It is noteworthy that this is the only time in his career that Singer uses his birth name. (Later he adopted “Y. Bashevis” for his Yiddish work and “Isaac Bashevis Singer” in English, along with a variety of pseudonyms.) There are at least two texts by Bashevis in this journal. “Vos dertseylt der mistiker fun tarnomiasto” (“The Story of the Mystic from Tarnomiasto”) is a work of fiction signed by him. The other, “Der banaler futurizm” (“Banal Futurism”), is unsigned, but from the style and content we can deduce it was also written by him. It is extremely interesting that these juvenile texts already show the direction of his future career as a storyteller, journalist, and critic. It’s quite possible that other pieces in the journal were also authored by Singer, for example “Shmuel hirshnzon,” a humorous sketch signed by Yitskhok Bleykhman (Isaac the Pale One)—a possible allusion to the writer’s pale complexion.

“The Story of the Mystic” is a satirical monologue ostensibly written by an erudite “mystic” who is diagnosed with tuberculosis. A mini foreword presents the work as the surviving, soiled fragments of a diary found in the dead man’s pockets. In an uncanny example of life imitating art, that’s exactly how it was with the discovery of the Salamandrye sheets themselves: soiled fragments from which we can discern the future Nobel Prize–winner’s style. The story also shows Bashevis experimenting with monologue—a narrative form he developed to perfection in his later tales.

The essay is a devastating, mocking critique of futurism. It’s another early example of a theme Bashevis would return to on many occasions—the futility of artistic and political ideologies and self-conscious literary experiments. The preserved part of the article concludes with ironic references to Yiddish modernists Uri Zvi Greenberg, Peretz Markish, and Melekh Ravitch.

Both pieces present Singer as a sharp and vivid observer, with a good sense of irony and a powerful visual imagination. In contrast to his later writings, these juvenile pieces seem less Jewish and more “cosmopolitan,” with references to Dickens, Oscar Wilde, Dante, and Dostoevsky. The sharpness of Bashevis’s pen strikes with full force in his attack on futurism, when he compares the futurist artist obsessively looking for new modes of expression and thus afraid to even glance at the moon, with a pious Hasid afraid of looking at a woman passing in the street.

While the story is set in the Bilgoraj region (Tarnomiasto stands in for the town of Tarnogrod—the Polish miasto and grod both mean “town”), the essay references a world outside the shtetl, in Warsaw and elsewhere. This too mirrors the pattern for years to come: Singer’s early stories and his first novel are all set in the provinces, while essays and interviews concern literary life in Warsaw.

The young Singer spent much of his teenage years in Bilgoraj, the town where his maternal grandfather was a rabbi, and it occupies a special place in his writings. His first novel, Satan in Goray, and a number of stories take place in the Bilgoraj region. In “Der yid fun bovl,” a Jew from Babylon is traveling from Lublin to Tarnogrod; Gimpel from “Gimpl tam” (“Gimpel the Fool”) comes from nearby Frampol. Bilgoraj also includes the Polish word raj, meaning “paradise,” and it’s noteworthy that the town often appears in Singer’s fiction as a synonym for paradise, with the phrase “gan-eydn” (The Garden of Eden) frequently used in the Yiddish originals of these stories.

In reality, life for the Singer family in Bilgoraj was very far from paradise. They lived in one room, in poverty, and with few real prospects for better times. But in Warsaw, and later in New York, Singer kept returning to the town in his imagination. When visiting Bilgoraj in 2003, the writer’s son, Israel Zamir, recalled that he had once asked his father if he would still be able to describe the shtetl. Bashevis answered, “Of course. Each house. Every street. If Jewish Bilgoraj still existed, I would easily get around there.”

Sadly, very few traces of the old Jewish Bilgoraj survive. All the more reason, then, to celebrate this unique discovery. Salamandrye has still not given up all its secrets. The journal was clearly typeset, but we don’t know whether it was ever actually printed and bound, much less distributed and sold. However, if only in part, the mythical journal has moved into the realm of reality.

—Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska

An earlier version of this article appeared in Yiddish in the Forverts.