Celia Dropkin's Paintings

A Poet Replaces Pen with Paintbrush

Celia Dropkin (1887-1956) is known for the boldness and honesty of her poetic imagery, its unrestrained carnality. "Dropkin is fierce and uncompromising, immediate and compelling, a radical thinker about women, the body, the conditions of love," Dropkin's translator, Faith Jones, wrote in Pakn Treger. "She is disgusting. She is intimidating. She is open, and cruel, and cruelest to herself. She is in love with the idea of love, yet certain that love is always fraught, contingent, and humiliating."

Rather softer are the images Dropkin created with her paintbrush.

In exploring our Dropkinalia, we came across a rare item in our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library: a collection of Dropkin's little-known watercolor and oil paintings. The slim volume contains almost no bibliographic information, only Dropkin's pictures, with titles in Yiddish and English, and none of the works from her one book of poetry, In heysn vint [In the Hot Wind], first published in 1935—though the title of the picture collection is given as Bilder fun "In heysn vint" [Pictures from "In the Hot Wind"].

The paintings in fact come from a later edition of In heysn vint, published in 1959 by Dropkin's children after her death. Though not yet available in our digital archive, this posthumous edition includes more poems, along with short stories and those curiously quaint pictures. In a biographical note at the end of the volume, Dropkin's friend Sasha Dillan wrote, "One would often find her on 57th Street, en route to the art school, with a heavy bundle of her canvases and other painter's tools. Exhausted, she shlepped herself along on her ailing, lame foot (the result of a sickness), weary but cheerful and revived—she had discovered in herself a new artistic talent!"

Russian-born Jewish-American painter Benjamin Kopman wrote an adulatory preface to her paintings, reproduced and translated below.

I also knew that she kept herself busy by painting in the last years of her life.

But when her son, Professor John Dropkin and Sasha Dillan invited me to take a look at the paintings, I, to tell the truth, thought, "A second Grandma Moses, a Jewish one, of course!..." But how amazed I was to see that Celia had accomplished in several years of painting what takes others decades.

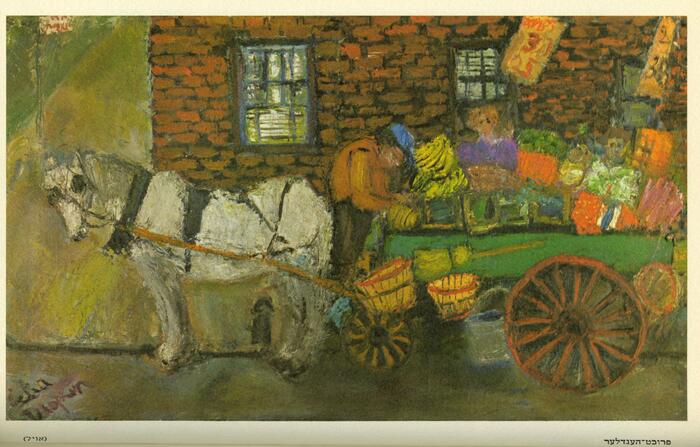

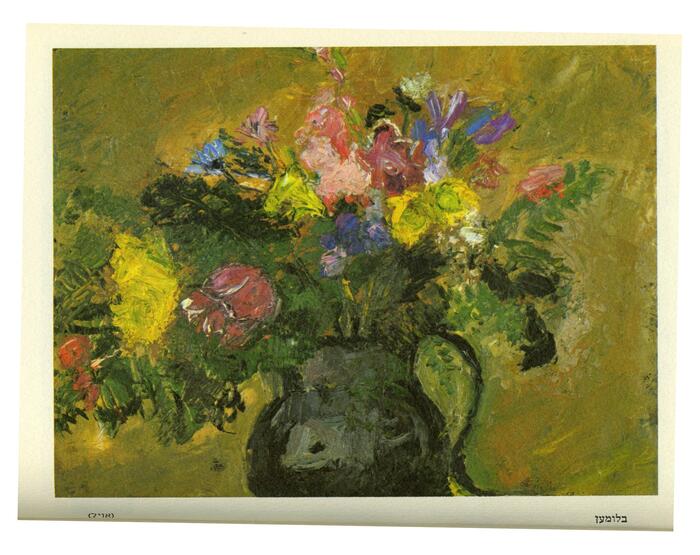

Only here and there does she display a beginner's helplessness. In general, it is clear that she had immediately grasped the concept of painterly technique. For example, the painting The Fruit Peddler—the horse, the cart— the whole thing is warm in feeling and professional in its technique. The small painting Flowers is very pretty. The watercolor A Woman in a Large Hat is artistically charming. Sentimentality and crudeness, which one finds in the work of almost every beginner, is in none of the paintings that I have seen...

If Celia Dropkin had devoted herself to painting in the same way she had poetry, she would have, without a doubt, reached the same level of perfection. She certainly had the talent.

איך האָב אױך געװאוסט, אַז פֿאַר די לעצטע יאָרן פֿון איר לעבן האָט זי זיך פֿאַרנומען מיט מאָלערײַ.

אָבער װען איר זון, פּראָפֿעסאָר דזשאַן דראַפּקין און סאָטשע דילאָן האָבן מיר געבעטן אַ קוק טאָן אױף די בילדער, האָב איך, דעם אמת זאָגנדיק, געטראַכט׃ "מסתּמא אַ צװײטע גרענדמאַ מאָזעס, אַ אידישע, פֿאַרשטײט זיך"...אָבער װי דערשטױנט בין איך געװען צו זען, ציליע האָט אין עטלעכע יאָר פֿון איר מאָלן דערגרײכט װאָס אַנדערע װאָלט עס גענומען יאָרן מיט יאָרן.

בלױז דאָ און דאָרט צײַגט זי אַן אָנפֿאַנגערינס אומבאַהאָלפֿנקײט. אין אַלגעמײן אָבער האָט זי, װי עס װײַזט אױס, גלײַך געכאַפּט דעם באַגריף פֿון מאָלערישער טעכניק. צום בײַשפּיל, דאָס בילד "דער פֿרוכט־פּעדלער" — דאָס פֿערד, פֿער װאָגן — די גאַנצע זאַך — איז װאַרעם אין געפֿיל און פֿאַכמעניש אין טעכניק. דאָס קלײנע בילד "בלומען" איז זײער שײן. דאָס װאַסער־פֿאַרב "אַ דאַמע אין אַ גרױסן הוט" איז קינסטלעריש חנעװדיק. אין קײן אײנעם פֿון די בילדער, װאָס איך האָב געזען, פֿילט זיך ניט קײן סענטימענטאַליטעט אָדער רויקײט, װאָס מען געפֿינט כּמעט בײַ אַלע אָנפֿאַנגער...

װאָלט ציליע דראַפּקין זיך אָפּגעגעבן מיט מאָלערײַ, װי זי האָט עס געטאָן מיט איר דיכטונג, װאָלט זי אָן צװײפֿל דערגרײכט די זעלבע מדרגה פֿון פּערפֿעקטקײט. דעם טאַלאַנט צו דעם האָט זי זיכער געהאַט.

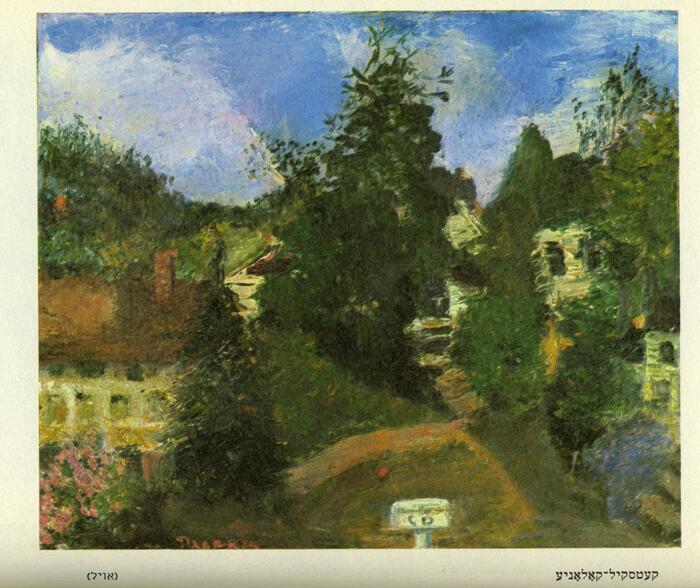

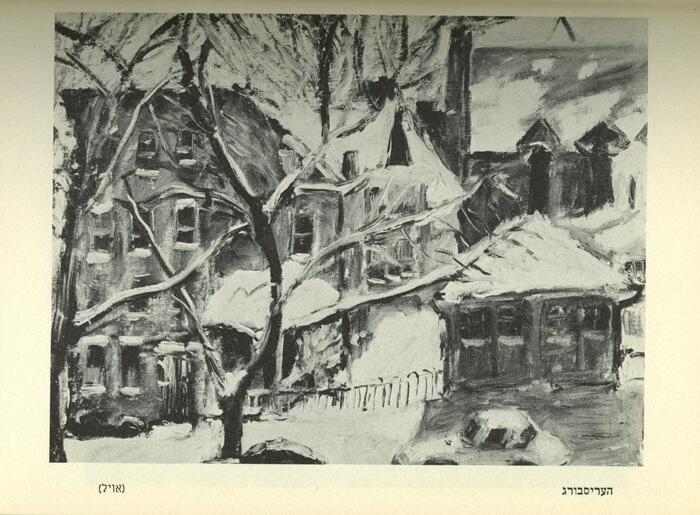

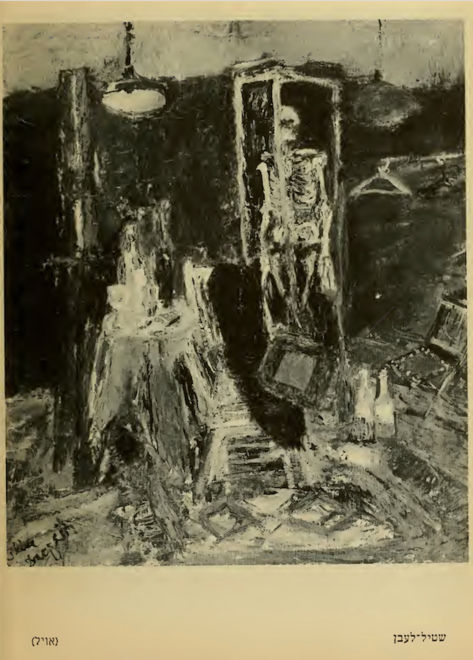

In the pictures, we see snow-dusted streets, vases of beautiful flowers, elegant ladies at rest, blue skies and green rolling hills. One still life (slide 6) does nod to the darker side of her work—a skeleton stands starkly in the background, lit by a harsh hanging light, assorted detritus covering the floor—as does the spectral A Lady in a Hat (slide 7). Still, we are mostly surrounded with prettiness: Manhattan's windswept Riverside Park is there, and the vast Catskills, and palm-scented Florida. The Catskills scene appears to depict Dropkin's own bungalow, as we can see in this detail: a mailbox with Dropkin's initials, which forms a double signature with her own name printed in the adjacent corner.

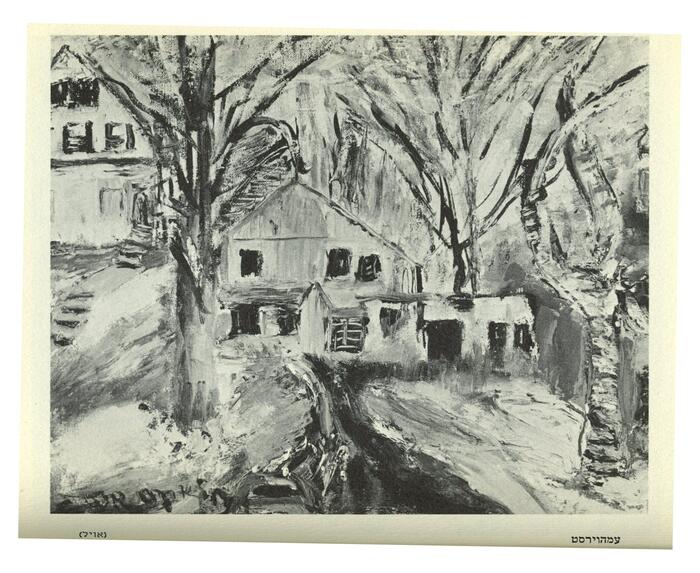

But most tantalizing of all is one unassuming oil of a rustic cottage, with a winding lane leading to it, all shaded over with spreading branches. Its title, rendered in Yiddish below the image? Emhoyrst. The table of contents clears it up: Amherst. We have looked into the possibilities of the poet's having traveled to Amherst, New York, (just outside Buffalo) or perhaps Amherst, Maine. She did live briefly in Virginia, where there is a hamlet called Amherst, but the apparent snow in the picture might preclude that possibility, and she lived in Virginia years before she took up painting. Our own Amherst, Massachusetts, however, seems likely to have attracted her—Dropkin was a devoted student of world literature, and it is not improbable that she wished to visit the hometown of one of her American woman poet antecedents: Emily Dickinson.

A likely Amherst-Yiddish connection that predates our Center by some thirty years, with a charming impression of our neck of the woods completed by one of Yiddish literature's most renowned experimentalists? Now this is a find from the vault that could have us vaulting with excitement over the nearest snow-covered branch, and fanning ourselves over "the hot wind" of discovery.

—Michael Yashinsky and Eitan Kensky