Gevalt in Our Stars

A Brief History of Yiddish Astrologic Practices

In a striking Rosh Hashanah greeting card from the early 1900s, an angelic figure festooned with flowers directs a group of children to look skyward: “Children! You are looking at the New Year star. May your luck shine just as bright and clear.” A shooting star passes through the frame of the window, bidding the viewers “a sweet year.”

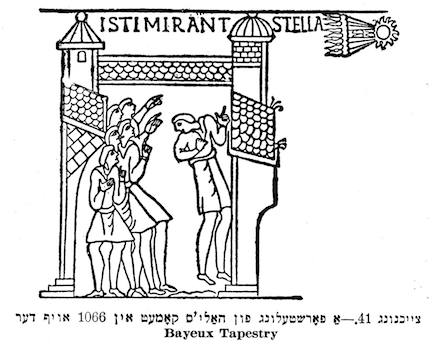

The idea of attaching one’s luck and fate to the movements of the cosmos is nothing new; early records from around the world show widespread acceptance of the heavenly bodies as authorities on earthly affairs. In Jewish culture, too, this belief was pervasive. Early Talmudic scholars argued over how great the influence of the stars was on daily life and even went so far as to create a complex numerological system with each of the planets corresponding to a different angel. Later, these angels came to stand for the twelve signs of the zodiac.

Although not Jewish by creation, the twelve signs of the zodiac are a prominent decorative feature of synagogues throughout the world. Both the zodiac and the Jewish calendar are governed by the cycles of the moon, so it makes sense that there was an early connection between the two. Since the invocation of the zodiac appeared widespread throughout Jewish history, I was curious if there were any books in Yiddish on the subject of astrology. When I had difficulty finding any with “astrology” in the title, on a whim, I picked up a few books on astronomy. Although today astronomy and astrology could not be more divergent disciplines, each of the Yiddish astronomical texts I read devoted a great deal of space to astrology.

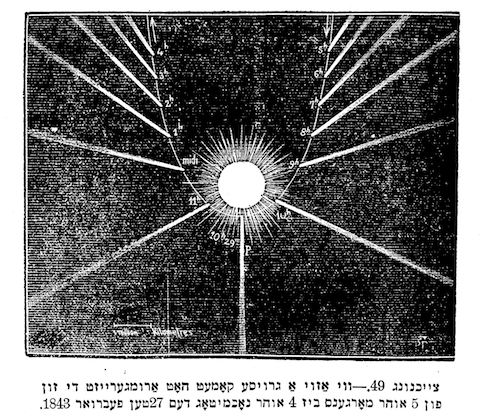

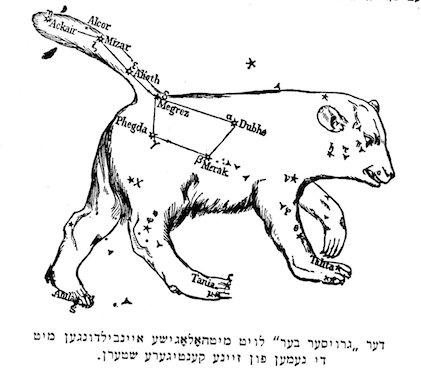

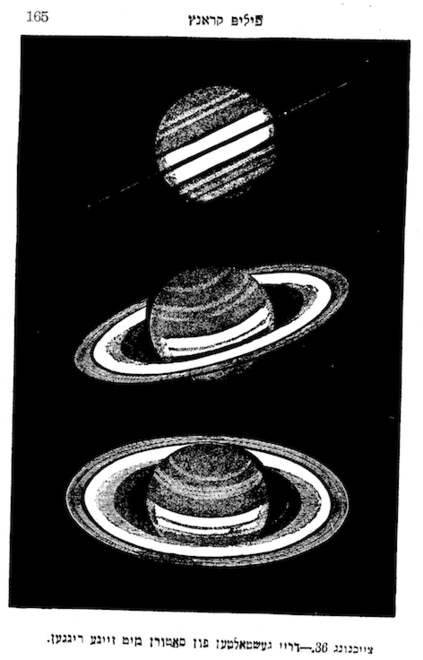

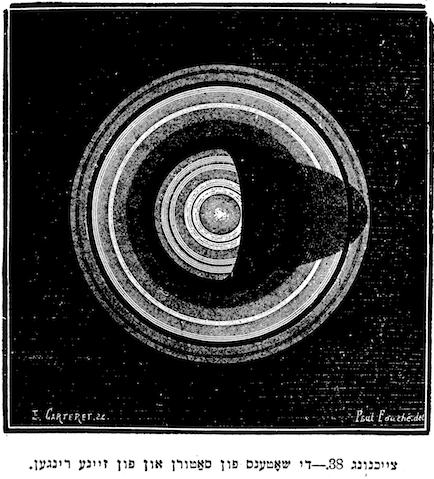

One of the first books I stumbled upon was Phillip Krantz’s 1918 Himl un erd: Astronomye farn folk [Heaven and Earth: Astronomy for the People]. Born Yankev Dombro in Radok, Ukraine, and trained at Petersburg Technical Institute, Krantz changed his name upon emigrating to the United States and made a living publishing science and history books for the lay reader. His book on astronomy, while lengthy, is clear and concise in diction and sprinkled throughout with helpful illustrations.

Krantz devotes an entire chapter to astrology, complete with three illustrations of Jewish zodiacs. He remains scientific in his tone and content and dismisses the idea that the stars are indicative of fate. Rather, Krantz is more interested in the stars that compose the constellations of the zodiac and the folk’s history behind their names and meaning. Combining history and mythology, on the sign Cancer he writes:

The sign “Cancer” (crab), known in Hebrew as sartan, is called thusly because when the sun reaches its greatest height in the Northern Hemisphere and begins to make its way back down (at the end of June when the days are the longest of the year), it moves backwards, like a crab.

דער צײכען „קאַנסער“ (ראַק) אָדער מזל סרטן, װען די זון דערגרײכט איהר גרעסטע הױכקייט אױף דער נאָרדליכער העלפֿט פֿון דער ערד און הױבט אָן איהר װעג צוריק אַרונטער (דאָס איז ענדע יוני, װען די טעג זײנען די לענגסטע פֿון יאָהר), זאָל שטאַמענ דערפֿון, װאָס אַ ראַק בעװעגט זיך ריקװערטס.

On the sign Libra, Krantz too mentions the significance of the equinox in the sign’s mythohistoriography:

The sign “Libra” (balance), known in Hebrew as maznim, occurs during the part of autumn when day and night become the same length and balance themselves, as if on the balance pan of the year.

דער צײכען „ליבראַ“ (װאָגשאָל) אָדער מזל מאַזנים האָט פֿאָרגעשטעלט די צײט, װען טאָג אונ נאַכט װערען גלייך אין הערבסט און באַלאַנסירען זיך אַזױ אױף דער װאָג־שאָל פֿון יאָהר.

One of the most fascinating elements of Himl un erd is the interplay between Hebrew, Latin, and Yiddish. In each of the excerpts above, the name of the sign is given in Hebrew, while the name of the constellation is phonetically spelled out in Latin. Finally, in order to clarify for the average Yiddish reader, who might not be familiar with such terms, the animal or object that represents the sign (such as the crab, for Cancer) is given in Yiddish.

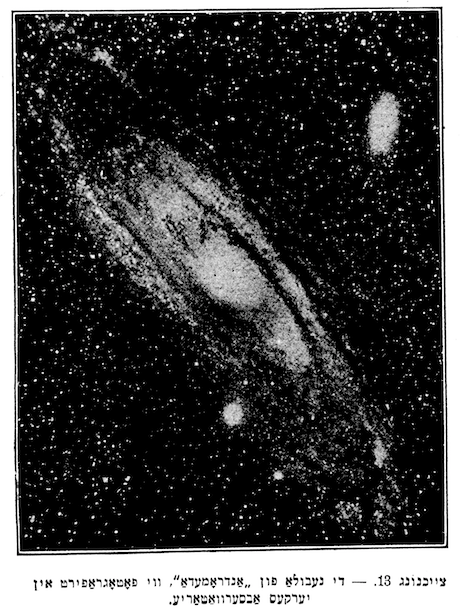

Ben-Zion Hofman’s 1918 Astronomye takes a different approach. Hofman, a popular writer for Der tog under the pen name Zivion, favored the vernacular names for stars and planets, most of which derive from Latin. Hofman too broaches the question of astrology in his text. In a chapter titled “Astrologie (Shtern-Zeeray)” ["Astrology (Star-Sighting")], Hofman promises to cover the following:

What is astrology? – The development of astrology and the belief in astrology during the Middle Ages. – The rules of astrology. – The belief that the stars have an effect on the luck of people.

װאָס איז אַסטראָלאָגיע? – די ענטװיקלונג פֿון אַסטראָלאָגיע און דאָס גלויבען אין איהר אין מיטעל־אַלטער. – די כללים פֿון אַסטראָלאָגיע. – דער גלױבען, אַס די שטערן האָבען אַ װירקונג אױף דעם מענשליכען מזל.

Hofman’s explanations of astrology are more in step with what is thought of as astrology today; each planet in Hofman’s schematic aligns with a particular domain of fate (Mars rules over conflict; Venus over love and friendship). As the earth orbits the sun, the planets assume different positions in the night sky, and those born under the influence of a particular set of celestial bodies exhibit qualities attributed to those bodies. Although Hofman himself does not believe in the luck of the stars, he is fair and balanced in his presentation of the history and methodologies of astrology. The section appears along with other early astral theories and thus makes sense in a scientific text on astronomy.

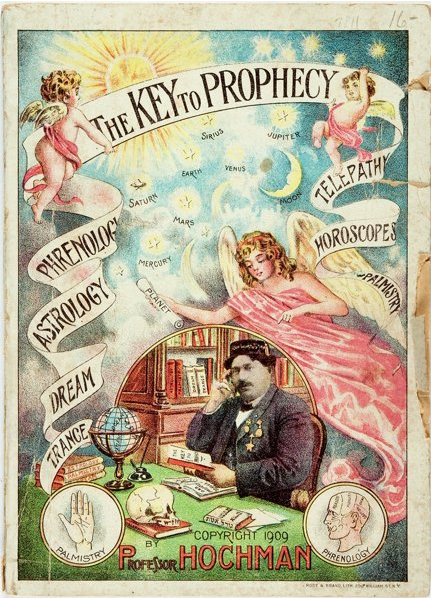

While both Hofman’s and Krantz’s texts are technical in nature, I also was lucky enough to get my hands on a mysterious brown book that takes a more mystical approach. Written in 1909 by Professor (Abraham) Hochman, this palm-sized work features a well-dressed man on the cover, surrounded by skulls, angels, and thick books on topics such as palmistry and astrology. In the expanse of night sky behind him lies a field of stars and planets neatly labeled for the reader.

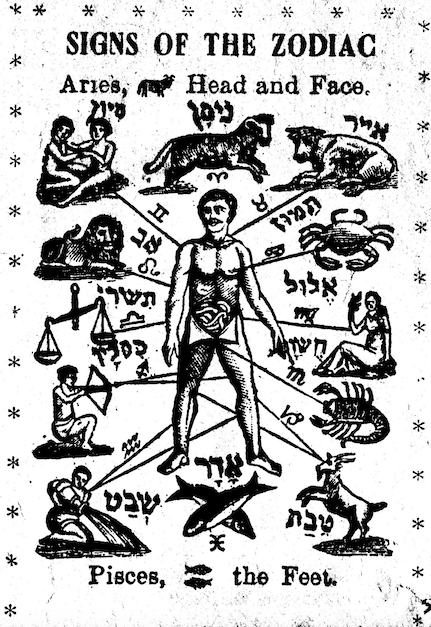

In Hochman’s text, the art of divining the future in the stars is taken seriously. Although Hochman does not focus explicitly on astrology, the stars and planets appear throughout the text. As a motif, they communicate to the audience that their fate is predestined by the planets that rule the sky at that particular juncture. One diagram even shows which signs rule over various parts of the body, perhaps in an effort to show which bodily endeavors may best behoove the reader.

Near the end of Hochman’s book lies a tool to help readers inquire about their own futures. With a handful of nuts and herbs and several convoluted charts, the reader can learn whether certain future events will have a favorable outcome. Following the same methods laid out more than a hundred years ago, several of my colleagues probed into their futures. The outcomes were mixed.

Curious to try the tool out myself, I asked one of the suggested questions: “Will I have a good legacy?”

“No,” came Hochman’s terse reply from the pages.

So what is the legacy of these astrological texts? Beyond a dedicated Yiddish readership, they could not have found much of an audience. None of these texts is particularly Jewish in content either. However, reading from these books today, it is the very Yiddish that made them once accessible to Jewish audiences that today marks them as specifically Jewish prophecies from the past. Without a working knowledge of Yiddish, these dossiers of divination become (major) arcana.

—Ozzy Gold-Shapiro