Hear and Attend and Listen

Kipling in Yiddish

Say what you like about Kipling—and plenty of critics have said what they disliked—as a storyteller he’s irresistible. He could find his way into anyone’s psyche; human or animal, it didn’t matter. His children’s stories are like incantations: “Hear and attend and listen” sends the reader (or the young listener) into a trance. His poems are eminently singable—the late English folksinger Peter Bellamy recorded several albums’ worth—and even his much-deplored patriotism is often mordant and critical in interesting ways. (George Orwell, after calling him a jingo imperialist, adds that “because he identifies himself with the official class, he does possess one thing which ‘enlightened’ people seldom or never possess, and that is a sense of responsibility.”) He was a more complicated man than his critics are usually willing to grant—and everyone has to grant that he was a master of narrative.

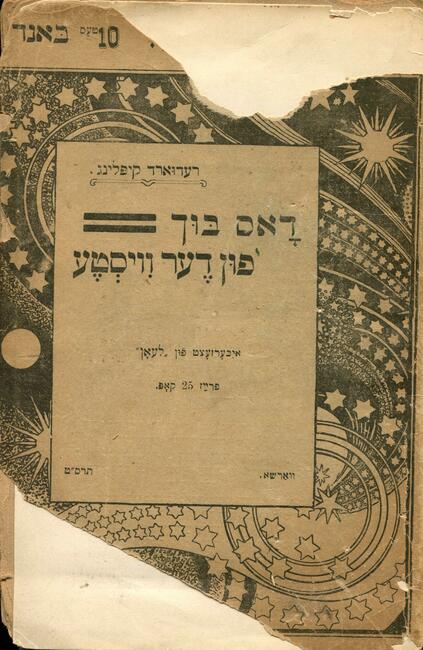

None of Kipling’s adult works have been translated into Yiddish, but various selections from The Jungle Book and& Just So Stories account for eight books in the Center’s Spielberg Library. (YIVO has several more.) The translators include some eminences of the Yiddish literary world. The 1908 Dos bukh fun der viste is simply signed “Leon” (possibly an early Leon Elbe?), but the eight stories in Dos bukh fun dzshongl (published by the Kletskin Farlag in Vilna, ca. 1913) were translated by Lamed Shapiro, best known for his searing pogrom stories, and the accompanying poems were splendidly rendered by Shmuel Halkin, who also translated works by Shakespeare and Pushkin. Note how Shapiro handles Mother Wolf’s ferocious defense of the just-adopted baby Mowgli from the tiger who has pursued him into her den (“Mauglis brider,” pp. 12-13):

And it is I, Raksha, who answers. The man's cub is mine, Lungri—mine to me! He shall not be killed. He shall live to run with the Pack and to hunt with the Pack; and in the end, look you, hunter of little naked cubs—frog-eater—fish-killer—he shall hunt thee!

און דאָס ענטפֿערט דיר ראַקשאַ—דו הערסט! דער מענשלינג איז מײַנער, לאָנגרי—אינגאַנצן מײַנער! ער װעט נישט געטױט װערען. ער װעט לעבען און אַרומלױפֿן מיט דער שאַרע און מיט דער שאַרע געהן אױף יאַגד; און סוף כּל סוף, הערסטו, דו מזיק געגען נאַקעטע קינדער—דו פֿרעש־פֿרעסער—דו פֿיש־טײטער—סוף כּל סוף װעט ער געהן אױף דיר!

Shapiro’s translation remained justly popular: “Dem kenigs ankus” (“The King’s Ankus”) was reissued by Kletskin as a separate pamphlet in 1920, and a revised edition with new illustrations was published by Farlag Emes of Moscow in 1936 as Mougli.

In 1924 in Vilna an unknown translator published “Kotuko,” an uncanny story of an Inuit boy and his dog that appears as “Quiquern” in The Second Jungle Book. And Sonya Kantor, of whom not much is known, translated several of the Just So Stories—“The Cat that Walked by Himself,” “How the Leopard Got his Spots,” “How the Rhinoceros Got his Hide,” “The Elephant’s Child,” and “How the First Letter was Written” (all published by Dos Bukh in Bialystok in 1920/21). Kantor also translated animal stories by naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton. Judging by “Vi azoy der lempert hot bakumen flekn oyf zayn hoyt,” her translations are unfortunately a little flat. Compare Kipling’s original:

"In the days when everybody started fair, Best Beloved, the Leopard lived in a place called the High Veldt. ’Member it wasn’t the Low Veldt, or the Bush Veldt, or the Sour Veldt, but the ’sclusively bare, hot, shiny High Veldt, where there was sand and sandy-yellowish grass."

For this, Kantor gives (p. 3):

In those ancient days, when everything was new and nice, the leopard lived in a place called the Highlands.

Remember it wasn’t a valley, not a wood, not a sour grassland—it was a bare and stony place, red-hot with the sun.

אין יענע אוראַלטע צײַטן, ווען אַלץ איז נײַ און שיין געווען, האט דער לעמפּערט געוואוינט אין אַ געגנט, וואָס האָט געהייסן ה ו י כ ל א נ ד.

זאָלסט גוט געדיינקען, אַז דאס איז געווען ניט קיין טאָל, ניט קיין וועלדל, ניט קיין זויערע לאָנקע—דאָס איז געווען א נאַקעטער און שטייניקער געגנט, צוגליט פֿון דער זון.

Kipling not only writes with effortless fluency, he’s a crazily doting father; his wordplay and dropped first syllables aren’t your garden-variety baby talk, they’re sparks thrown off by a high intelligence enthralled with love for a small new person. Kantor conveys the general meaning of the passage, but she’s not having nearly as much fun.

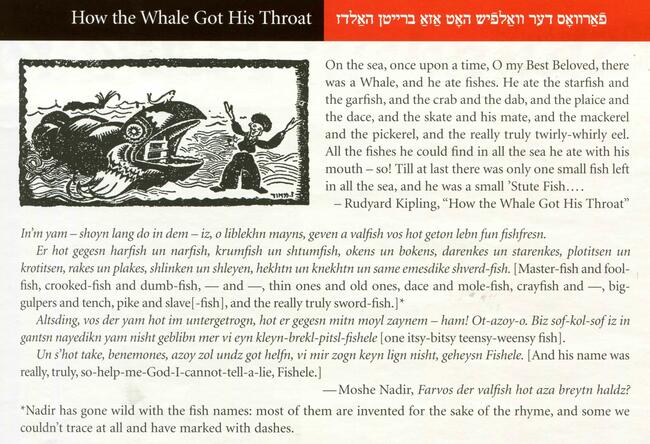

Not so satirist Moshe Nadir, whose translations of “How the Whale Got His Throat” and “How the Camel Got His Hump” (Vilna, 1928) are as scintillating and funny as the originals. Somehow—perhaps bedazzled by Nadir’s brilliance—the publisher neglected to credit Kipling on the title page, but “O, liblekhn mayns” is unmistakably “O my Best Beloved.”

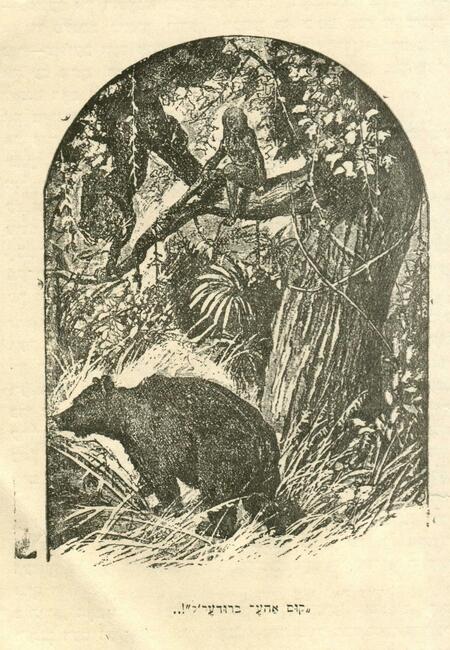

The illustrations, when there are any, are also worth looking at. The Nadir translation has a picture of whale and mariner by artist and puppeteer Zuni Maud. Between the 1913 Vilna edition and the 1936 Moscow edition of The Jungle Book, Mowgli and his companions stop looking like nineteenth-century clip art and acquire a sinuous energy; the later artist, V. Vatagin, was clearly influenced by cave paintings. (Vatagin’s illustrations also appeared in a Soviet translation of The Jungle Book into Russian.)

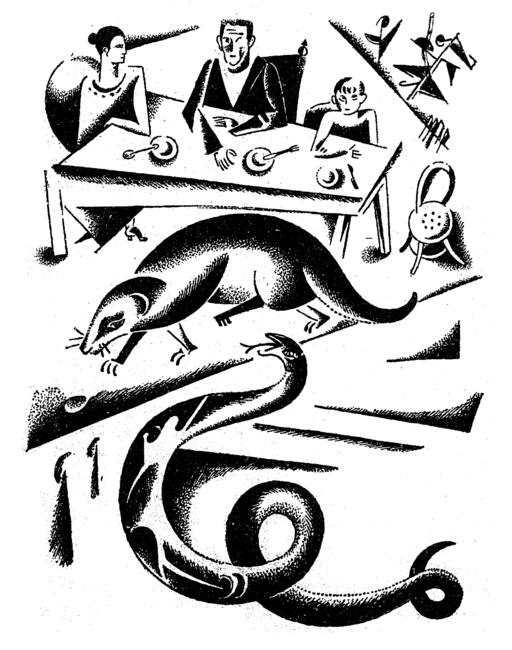

The big surprise in this realm is M. Epshteyn’s fiercely energetic modernist drawings for “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” (Kiev, 1924, translated by H. Lyumkis), which seem spring-loaded, charged with the coiled energies of cobra and mongoose. No socialist realism here.

Had Yiddish literature been able to continue at full force, some of Kipling’s adult works might have been translated; in Israel, Hebrew translations have been published of Kim, The Light That Failed, and Soldiers Three (which is set in Afghanistan and was written in the 1880s). In a time whose political assumptions are very different from Kipling’s—as Orwell remarks, post-Hitler it’s hard to imagine real moral accountability in the political sphere, or believe it “possible to overcome force except by greater force”—it still may be that the old storyteller hasn’t said his last word.

—Catherine Madsen

Author’s note: Transliterated passages follow the original text, so spellings are sometimes nonstandard.