Peace, Love, and Understanding: Exploring Yiddish Culture through Sheet Music

What does it mean to see music?

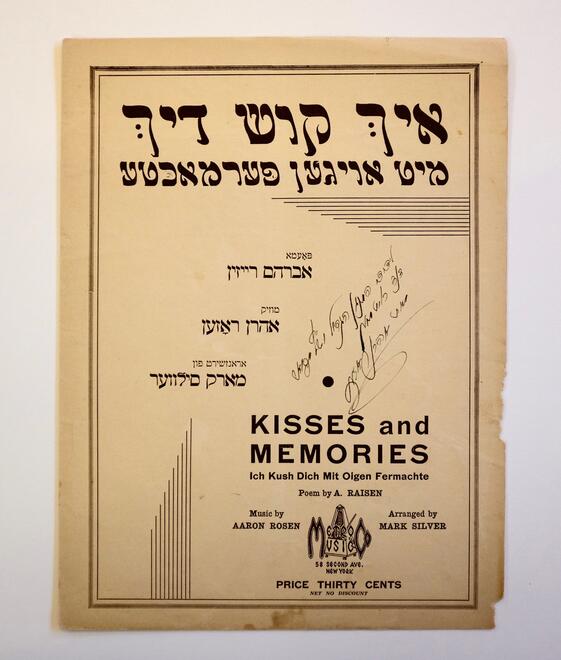

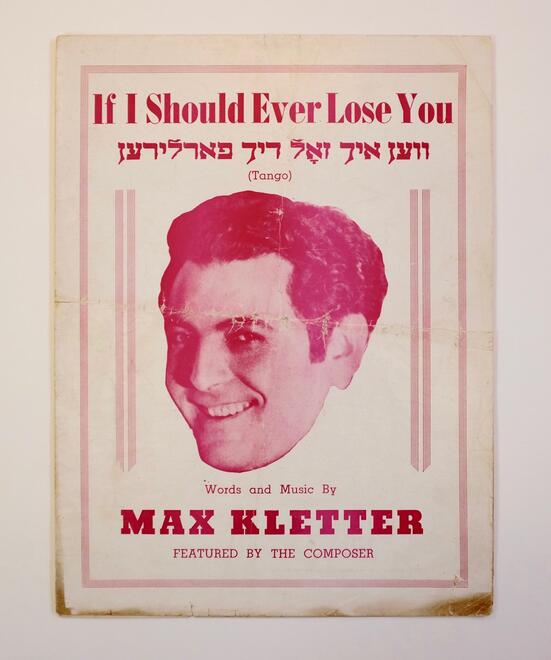

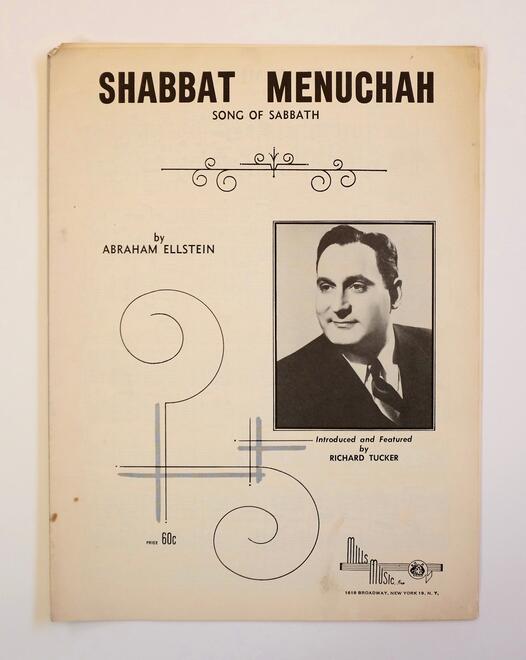

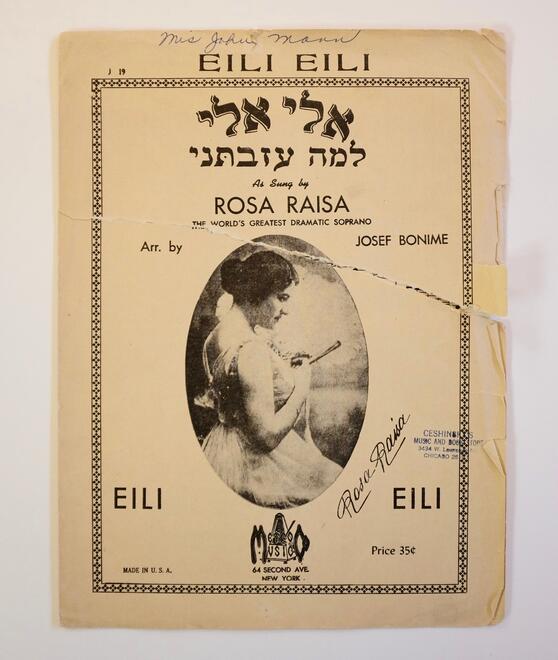

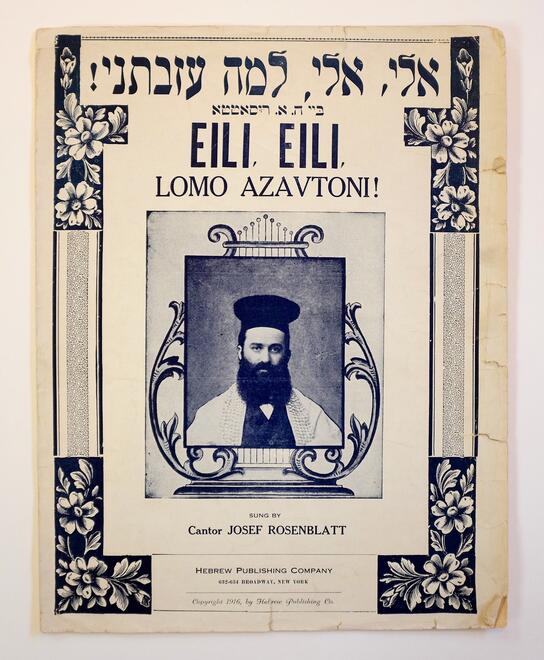

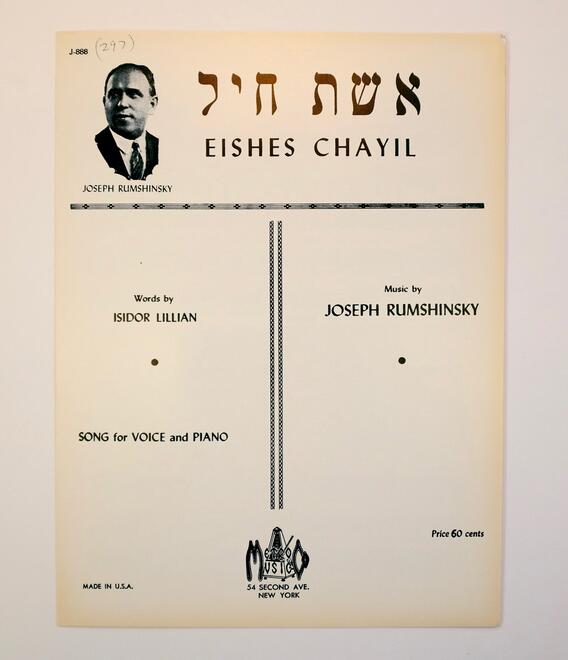

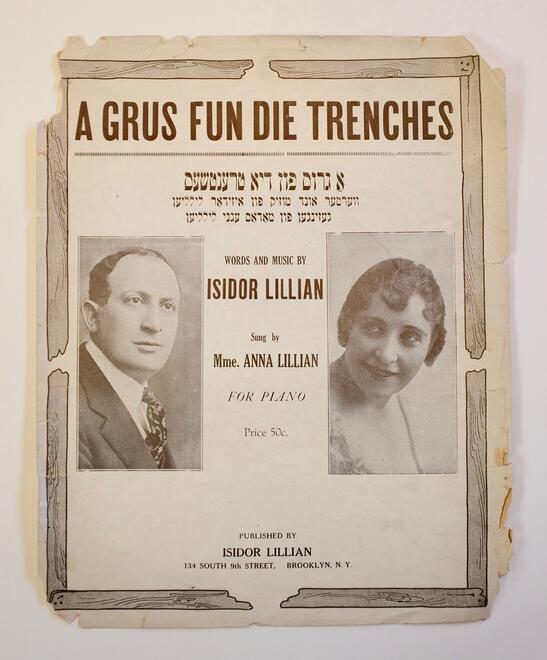

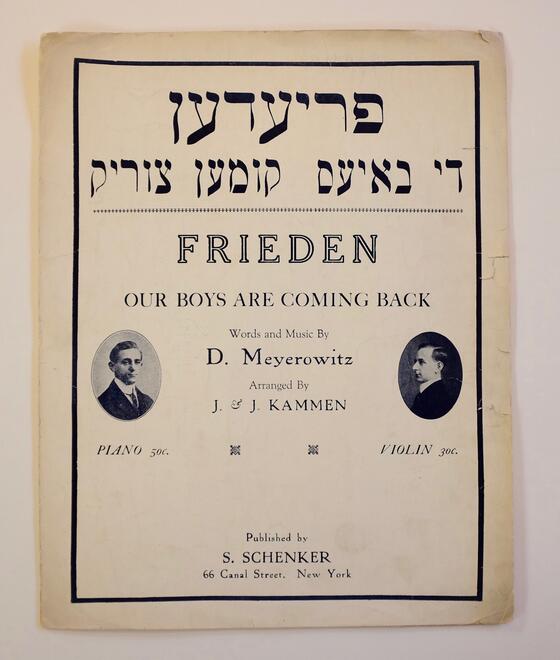

In the days before commercial recordings, it meant sheet music, which featured the music of the day notated, with lyrics underneath the notes. These pieces—often featuring brilliantly illustrated covers with headshots of the composer, lyricist, or star performer—allowed audiences to access their favorite songs, though it meant they had to recreate the music themselves, usually on the piano.

Stacked in the repository of the Yiddish Book Center are approximately 1,000 titles of Yiddish sheet music, representing a sizable percentage of works published by the Metro Music Company and the Hebrew Publishing Company, two prominent publishing firms of New York’s Lower East Side in the first half of the twentieth century. We were fortunate to receive these collections virtually untouched, so visitors to the Center can access pristine copies of a wide selection of works. And we’ve spent the last few months working to make the items in this collection easier to discover and use.

But the Yiddish Book Center’s vault holds sheet music of a different kind: those received from personal or group donations, including large numbers from Yiddish musical theater productions. While this is an interesting—and extremely diverse—selection of Yiddish music to explore, the nature of their use meant that many of them had not been treated well by time. It also meant that protecting and organizing these sheets presented a particular challenge.

Though this work was difficult, it took on a great deal of meaning for me. We weren’t only placing sheets in archival sleeves, we were preserving the physical marker of someone’s emotional and spiritual connection to a piece of music. As a musician, I have always been struck by music’s ability to communicate directly with the emotions of the audience. So for me, coming across sheets with names in the corners and handwritten notes scrawled in the margins helped me understand—clearly and profoundly—the relationship between the notes on the pages and the real experiences of people playing that music. These sheets are a tangible way for people to experience the music that touched and inspired them.

As I continued to explore the collection, the sheets began to tell stories. They revealed trends, tastes, concerns, and musical sensibilities—of the communities they came from and the audiences they entertained. Many of the largest publishing companies were based in New York City, allowing them to respond intimately and immediately to the people buying their music. Using this collection, we can learn about the consciousness of the Yiddish-speaking communities of this era, and in doing so, we can better understand their feelings about romance, religion, and politics.

In America, the expression of romantic love was much more open than it had been in rural Eastern Europe—an expression well represented in popular Yiddish songs of the early twentieth century such as “Ikh bin farlibt” (“I’m In Love”), “Sheyn vi di levone” (“Pretty Like the Moon”), “Ikh kush dir mit di oygn farmakht” (“I Kiss You with Eyes Closed”), and “Ven ikh kuk af dir” (“When I Look at You”). The love song “Bet mikh abisele, mamele,” translated as “Coax Me a Little Bit,” displays an interesting mix of Yiddish and English that was a feature of some popular music of the Yiddish theater. The singer claims: “Gloyb mir az ikh ken di toyre / gloyb mir az ikh hob di skhoyre / ikh ken promis tsu delivern di goods,” translated as, “Believe me that I know Torah / believe me that I’ve got the wares / I can promise to deliver the goods.”

Yiddish popular music publishers also included liturgical and religious songs in their catalogues. Songs such as “Eli, eli” and “Bame madlikin” derived from Jewish religious tradition, were often published featuring popular cantors such as Joseph Rosenblatt on their covers. The traditional Sabbath song “Eyshis khayil” honoring “women of valor,” inspired a jazz arrangement with words by Isidor Lillian and music by Joseph Rumshinky, one of the most prolific Yiddish popular music composers. This arrangement, performed by the Barry Sisters and Moishe Oysher, among others, indicates demand in the community for references to traditional, religious songs that the publishing companies worked to meet.

But the most fascinating category of sheet music for me is political songs. Many Yiddish songs, including those that achieved widespread popularity, dealt with overtly political and social themes. This is an interesting feature of Yiddish music, and one that contrasts with the output of mainstream American music publishing at the time. American firms tended to avoid politics, except to stoke patriotism in times of war. Yiddish music also depicted reactions to war, specifically World War I. “A milkhome” (“A War”) is adorned with a stark image on the cover, depicting a skeleton conducting an opera of soldiers in combat. Looking down upon the production are six world leaders, each depicted in royal garb and identified in Yiddish. “A grus fun di trenches” (“A Greeting from the Trenches”) and “Friden: Our Boys Are Coming Back” deal directly with American involvement in World War I.

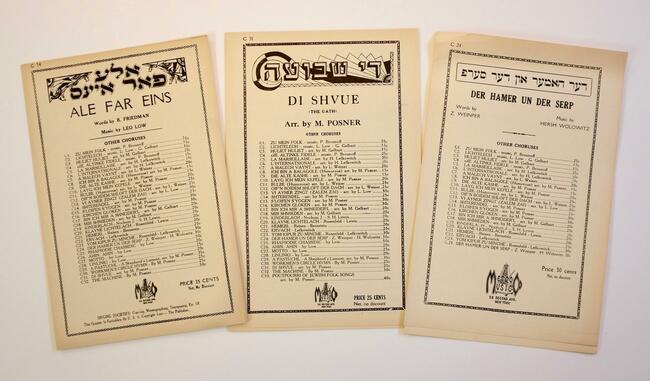

Politically leftist songs, inspiring support for socialist and labor causes, were common among Yiddish publishers. For example, the song “Ale far eyns,” published by Metro Music with music by Leo Low, promoted unity among workers, with a chorus of “ale far eyns, un eyns far ale” (“All for one, and one for all”). “Der hamer un der serp” (“The Hammer and Sickle”), also published by Metro Music, clearly refers to the communist movement, while a Yiddish version of the socialist anthem “L’Internationale” was written by Henry Lefkowitch, a composer and publisher of popular Yiddish music. Metro Music also published a version of “Di shvue,” the Bundist anthem written by S. Ansky. These examples indicate the intersection of leftist politics and popular music that characterized the Yiddish music publishing industry.

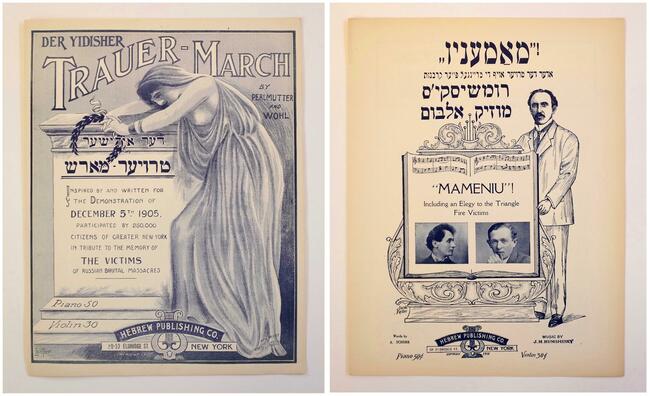

Sheet music could also draw attention to current events—for example, in the case of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, in which 146 garment workers died. Joseph Rumshinsky responded with a song called “Mameniu,” which speaks directly of the “korbones,” victims of the tragic event. After 250,000 New Yorkers came together to protest pogroms on December 5, 1905, Hebrew Publishing Company released a song titled “Der yidisher troyer marsh” (“The Yiddish Sadness March”). These songs indicate a dedicated political consciousness of Jewish audiences that was served by the local music publishing industry.

The wide range of topics represented by these songs allows us, in 2018, to look back on the Jewish-American experience one hundred years ago. Sheet music is a tremendous resource because so much information—musical and otherwise—is captured on the pages, bringing Yiddish language and culture to life. Exploring this collection has allowed me to envision and empathize with a vibrant aspect of Yiddish life, which, as a student of Yiddish, is extremely valuable and fulfilling. This process has forced me to reflect on the ways music reflects the society in which it develops.

In a hundred years, when people look back on 2018, what will the music of our time tell us about the way we lived and the things we cared about?

—Zeke Levine