Pogrom Literature and Collective Memory

by Sarah Quiat, Yiddish Book Center fellow

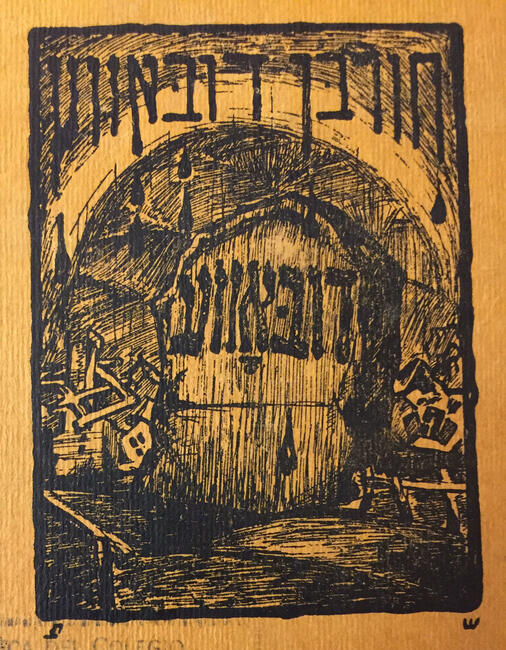

Of all the written accounts of pogroms in the Yiddish Book Center's collection, we know of only one authored by a woman: Rokhl Faygnberg’s A pinkes fun a toyter shtot (khurbn dubove) (Chronicle of a Dead City: The Destruction of Dubove). Though the author was a survivor of pogroms, A pinkes fun a toyter shtot is not a personal account of her experiences. Instead, Faygnberg creates a record of a devastating 1919 pogrom in Dubove, and through this work exemplifies how a book can preserve the memory not only of its previous owner and its author but of an entire community.

An Early Memorial Book

Following World War I and the 1917 Russian Revolution, pogroms swept through Ukraine, resulting in death and displacement for many Jewish residents and, in some cases, the death or disappearance of an entire Jewish community. Ruhama Elbag’s article in Haaretz, “The Fields of Memory are Wide Open,”contains a translated excerpt from A pinkes fun a toyter shtot describing Dubove after the violence in 1919:

During the time of the autumn holidays the farmers of [Dubove] destroyed the Jews' houses, which stood there in their wreckage, and plowed it to serve as fields and gardens. They also destroyed the Jewish graveyard. They destroyed the tombstones, and plowed and sowed the land with winter crops. Later the synagogues were razed and potatoes were planted where they had stood.

This process of destruction, occupation, and repurposing is striking. Through it, the Jewish community and its history are physically erased from Dubove. A pinkes fun a toyter shtot (khurbn dubove) is the remaining record. Yet, the book’s author does not focus solely on the death, destruction, and erasure we see in this passage. The book depicts the Jewish community of Dubove in its life and in its death: before, during, and after the pogroms.

Though David Roskies refers to it as a “documentary novel” in his YIVO article entitled “Memory," A pinkes fun a toyter shtot is written in a style that closely resembles the later yizker bikher (memorial books) written by and for survivors of the Holocaust, and its format includes chapters that draw from the specific memories and testimony of town residents. This text is an example of a memorial book that precedes the Holocaust, created to mourn and memorialize communities destroyed by pogroms and earlier anti-Jewish violence.

The title of the book includes two terms that help us to understand the genre and the context for the book: “pinkes” refers to a register or book of records, annals or chronicles, and is particularly used within the context of a Jewish organization or community. Shtetls typically had a pinkes, a book where the noteworthy events of the Jewish town, whether good or bad, would be recorded. The term pinkes in this title thus refers to a longstanding tradition among Jewish towns. Yet, rather than functioning as a living and ongoing chronicle of the town, the book acts as a chronicle of its death: the book's publication is occasioned by the town's destruction.

The use of the word “khurbn” also has important implications. Khurbn means destruction, disaster, and devastation in Yiddish, and, while it became the Yiddish term for the Holocaust, it was and continues to be used to describe other major catastrophes in Jewish collective memory, especially the destruction of the First and Second Temples of Jerusalem. Faygnberg invokes this term to connect the destruction of Dubove to a longer chain of disasters in Jewish history.

When learning about anti-Jewish violence today, we often focus on the destructiveness of the Holocaust. It is worth remembering that the destruction resulting from World War I and anti-Jewish violence surrounding the Russian Revolution were unprecedented in scale at the time. Dubove was not the only Jewish community to be erased in this period. A pinkes fun a toyter shtot (khurbn dubove) exemplifies a response to anti-Jewish violence that preceded and influenced memorialization after the Holocaust. Though the words pinkes and khurbn hold many meanings, the message in the title is clear: the town of Dubove was destroyed—this is its story.

Rokhl Faygnberg (Imri)

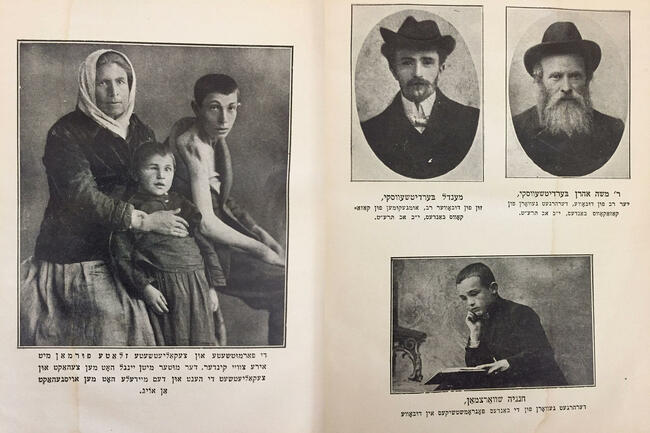

The subject of several contemporary scholars’ work, Rokhl Faygnberg continues to interest academics and lay-readers alike. Faygnberg, born in Lyuban, Minsk region, White Russia in 1885, was a prolific Yiddish and Hebrew writer particularly known for her romance novels, which explored the shifting landscape of traditional Jewish life. Her entry in Zalman Reyzen’s Leksikon fun der Yidisher liṭeratur, prese un filologye (Vilne, 1929) contains a full list of her works (through 1929), as well as information about her life. Beyond details about her writing, Reyzen’s profile includes background about her childhood, her marriage in 1914 to a pharmacist twenty-five years her senior (a relative of her mother’s family), their son, and Faygnberg’s own experience of the pogrom waves in Ukraine in 1919.

Five years after she and her new husband settled in a shtetl called Yanovke (today Bereslavka, Ukraine), pogrom attacks destroyed the town, and she and her son went into hiding for the summer. They then moved to Odessa, where Faygnberg remained briefly before leaving for Kishinev, Bucharest, and Paris, documenting Jewish life in each place she went.

After the 1919 pogroms in Ukraine, Faygnberg turned her attention to documenting and writing about the pogroms. In addition to A pinkes fun a toyter shtot and newspaper and magazine articles about the events, she also published Oyf di bregn fun dnyester (On the Banks of the Dniester), which recounts her interactions with displaced victims of the pogroms on the Bessarabian-Ukrainian border.

Where Zalman Reyzen’s profile on Rokhl Faygnberg ends (considering Faygnberg was still active during and after its publication in 1929), Sheva Zucker’s article for the Jewish Women’s Archive continues, following Faygnberg to Mandatory Palestine in 1933. Among the many accomplishments that Zucker highlights in this chapter of Faygnberg’s life, her project to create her own publishing house, Me’assef, is particularly notable. Though Me’assef only published three volumes of Hebrew translations of Yiddish works, Faygnberg founded this publishing company with an ambition to ensure that Yiddish literature would be incorporated explicitly into the future of Hebrew publishing.

A published memoirist by the age of 23, Rokhl Faygnberg explored and contributed to the worlds of memorialization, recordkeeping, and literature more broadly. From the reflections on her childhood in her 1909 memoir, Di kinder yorn (Childhood), to A pinkes fun a toyter shtot, to her publishing company, Faygnberg utilized the page as a powerful platform to amplify suppressed voices and their stories.

Journey of One Book

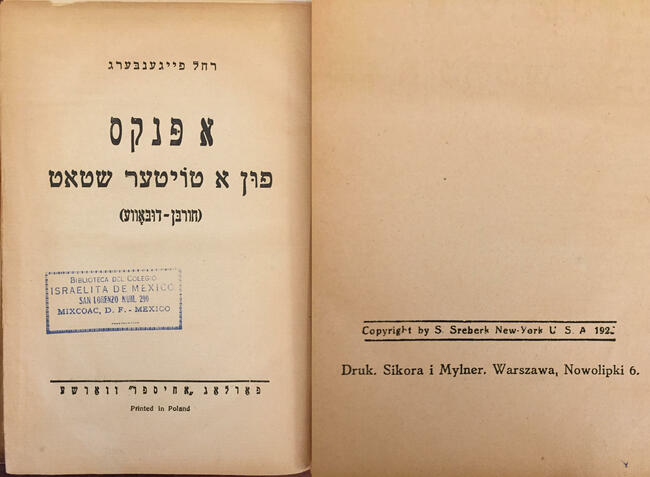

Though questions about when and where the book originates should be among the most straightforward to answer, this book provides an example of how beautifully complex these answers can be, and how many stories lie waiting in every Yiddish book. This copy of A pinkes fun a toyter shtot, which lives in the Yiddish Book Center’s vault, lists publisher Farlag “Ahisefer” Varshe on the title page. Written below it in English is “Printed in Poland.” We turn the page to find written “copyright by S. Sreberk, New York USA 192(?),” the last number in the year ill-printed.

Those first questions about when and where lead us to others: Who is S. Sreberk? Why was this book copyrighted in New York if it was published in Warsaw?

As it turns out, Shlomo Sreberk was one of the partners in the major Yiddish and Hebrew publishing syndicate Tsentral, based in Warsaw. A sign of Tsentral's importance and size was its established relationships outside the Russian Empire. This explains the valuable New York copyright, and provides us with interesting context for the book’s intended audience. Ahisefer was one of Tsentral's Hebrew publishing subsidiaries, so it is somewhat unclear why this Yiddish book was published under its auspices. What began as a search for basic background information for the book thus leads us to many more details about the world of Yiddish publishing, and to further questions about the book’s intended audience and impact.

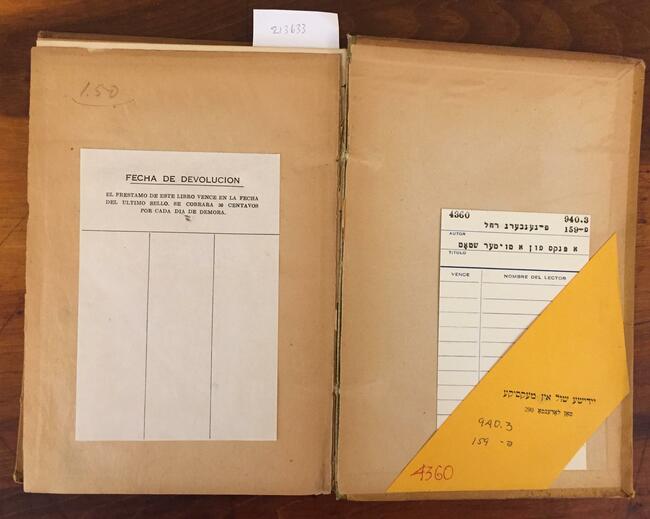

A book that lives at the Yiddish Book Center has a history that extends beyond when and where it was published to the individuals or institutions that the book belonged to after its publication and before its arrival at the Yiddish Book Center. We don’t always know who the previous owner is, but sometimes the book itself can tell us: in this case, the name is stamped on the front cover and title page, a simple and slightly faded label that reads:

“Biblioteca del Colegio, Israelita de Mexico, San Lorenzo num, 290. Mixcoac D.F. Mexico.”

This particular copy of A pinkes fun a toyter shtot was in the school library for Colegio Israelita De Mexico, the first Jewish day school in Mexico City, founded in 1924. For many years, it had a strong Yiddish language program. Though that program is no longer at the school, the vibrancy of Yiddish in Mexico lives on through former students, teachers, and affiliates of the school system. It also lives on through books like A pinkes fun a toyter shtot that are, quite literally, stamped with the memory.

A pinkes fun a toyter shtot has been used in various ways throughout its history, encapsulated within this copy of the book, as well as others. This includes playing an important role in Paris during the 1927 trial of Sholem Schwarzbard, who faced charges for assassinating the leader of the Ukrainian national forces. Moïse Twersky’s French translation of the book was used as a key document in Schwarzbard's trial, providing evidence of the Ukrainian nationalist forces' influential role in the massacre of thousands of Jews during the 1919 pogroms in Ukraine.

The stories that this book carries with it have been folded into its pages from all over the world: a shtetl in Ukraine finds its story published in Poland and copyrighted in New York. That story travels into the courtroom at Schwarzbard's trial, and into the library of a school in Mexico City in the form of this book, only to find a home today in Amherst, MA. From 1919 to 2019, these 100-year old memories continue to live, nestled among many others at the Yiddish Book Center.

A Text Full of Memories

Each chapter, each sentence, and each word in this book has a story to tell. From the layered title to the layered pages, it is a text full of memories. Faygnberg records the stories of witnesses and survivors in a narrative voice that is removed and even, painting a picture of the Jewish residents and their lives before, during, and after the pogroms. The text, though analytical and objective in tone, does not read as academic or scholarly; Faygnberg does not share specific sources for information or a particular critical interpretation. Not exactly an academic work, it is also not exactly testimony, because the author was not present for the pogroms she chronicles here (nor did she live in Dubove that we know of).

Yet, the power of this book is clear: through its key role as a document in Sholem Shwarzband’s defense, through its journey from one Jewish community to another, and through its connection to modern-day yizker bikher, we witness the individual voice become the place for collective expression, a singular object representing an entire community. Through her writing in A pinkes fun a toyter shtot, Rokhl Faygnberg created a collective memory for this and other communities that were destroyed in the 1919 Ukrainian pogroms—communities that could no longer speak for themselves.