The Story Behind the Yiddish Book Center's Yiddish Typewriter Collection

These Yiddish typewriters have stories to tell about the companies that made them and the writers who used them.

Although the Yiddish Book Center’s mission is to rescue and preserve Yiddish books, over the years we’ve received a number of other items related to Yiddish. One of the most interesting collections that we’ve accidentally cultivated is our collection of Yiddish and Hebrew typewriters. Some of the typewriters were picked up by zamlers as they collected books from the homes of Yiddish writers or their family-members. Others were shipped to us or dropped off at the Center by donors. In the early days of the Center, many of the typewriters, like many of the books we collect, were returned to use by students or administrators. As the demand for typewriters declined, however, the remaining typewriters began to sit idle at the Center, watching history pass them by and waiting to be rediscovered.

This fall, my colleague Sophia Shoulson and I decided to investigate the collection. We ventured down to the basement where they were then stored and squeezed past retired exhibit displays and boxed-up music festival materials to find them: 26 typewriters, dimly visible on a range of shelving. Each had its own personality. Some sat bare on the shelves, showing their frames, some small and delicate and others heavy and solid, imprinted with various company names and stickers from by-gone shops, keys flashing different arrangements of Yiddish letters. Others sat within wooden covers or latched leather carrying cases with worn handles. They beckoned to us like a box of assorted chocolates.

Over the past couple of months, as we’ve catalogued, rehoused and researched the collection, we’ve become well acquainted with the quirks and individual charms of each typewriter. Thanks to an article by Nick Block we’ve learned to identify typewriters specifically designed for typing in Yiddish (we also have some Hebrew typewriters in our collection, some of which were definitely also used for typing in Yiddish), and learned to understand the place of these machines within the history of Yiddish typewriters. We’ve also read up on general typewriter history, dug up Yiddish typewriter advertisements and found mentions of typewriters in Yiddish literature, to better understand how these machines were used and how people thought about them. Finally, we’ve spent a good deal of time looking at the typewriters and learning from them directly. Each step of the way, I find new reasons to love Yiddish typewriters. Let me introduce you to five of my favorites!

The Classic: Remington 92

Year: 1928

Why to love it: it’s a classic

The Remington is the quintessential Yiddish typewriter. According to Nick Block, not only did the Remington Typewriter Company (based in Ilion, New York) produce the very first Yiddish typewriter in 1903 but Remington also established the standard Yiddish keyboard layout and continued as one of the two largest producers between 1910 and 1940, the heyday of Yiddish typewriter production. Although this particular Remington typewriter was made in 1928, 25 years after the first Yiddish Remington, it still has a solid, rectangular frame very similar to the earliest model (the earliest design is pictured in the 1906 advertisement below). This 1928 version of the Yiddish Remington has a couple of special touches: “Remington Writing Machine” painted in Hebrew above the carriage and at the bottom of the frame, and shift keys labeled in Yiddish.

Early advertisements for the Yiddish Remington market the machine as a practical investment and a cutting-edge technological advancement. One ad, run in 1906, claims:

"This new Yiddish Remington must be owned and used by all those who are occupied with writing. It’s easy to learn, easy to operate, writes twice as fast as with a pen, works cleanly, legibly and attractively and as soon as you try it, it pays for itself by saving time, work and expenses."

A 1911 advertisement, run in the Yiddish-language “Jewish Farmer” periodical, markets the Remington typewriter specifically to farmers:

"The farmer must have this business machine... You need it because it saves you much precious time. With only a tiny bit of practice you or a member of your family will be able to write twice or three times as much as with a pen."

Advertisements for the Remington Typewriter

Whether used for writing in the home or as a business machine, owning a Remington lent an air of sophistication. The 1906 ad boasts: “The Remington typewriter is now and has always been the recognized leader among typewriters. The new Remington equipped with Yiddish type is the latest form of this world-famous machine.” By the time this Remington 92 was built and put on the market, the Remington company already had 22 years of experience producing Yiddish typewriters, and production was still going strong. It’s easy to imagine the owner of this typewriter swelling with pride while typing on their new Remington 92.

Sweet and Simple: the Corona XC-R

Year: 1926

Why to love it: it’s a beauty

Unlike other companies, such as the Underwood Typewriter Company, which largely mimicked the Remington when designing its Yiddish typewriter, when the Corona company set out to design a Yiddish typewriter in the 1920s, it took its own approach. The results are beautiful. The simple keyboard layout of the Corona XC-R lacks all but one of the special keys included in the standard layout used by Remington and Underwood—it retains only the komets alef, located in the upper left-hand corner. Despite the omission of the other keys, Nick Block explains that it was designed to be a Yiddish typewriter, as evidenced by its “XC-R” model name, the “R” indicating that the carriage moved right to left, and the designation “Y” (probably for “Yiddish) that was used for the parts for this model. This minimalist approach to the keyboard, while somewhat surprising because the Corona XC-R bucked the standard set by Remington and Underwood, fits in perfectly with the overall goal of the Corona XC-R’s design: simplicity.

A “Corona Special” manual that I found in a case with one of our XC-Rs states on the first page that “while possessing all the labor-saving devices of the modern correspondence typewriter, Corona is extremely simple in construction and operation, there being only 690 parts as opposed to 2,000 or 3,000 in the ordinary machine.” This streamlined design is also very portable: the Corona’s carriage folds down to make a compact rectangle that fits right into a small case. The simple design also happens to be, in my opinion, extremely cute. The petite, rounded frame of the Corona XC-R curves into a smile (or is it a mustache?) below the carriage, which sticks out on either side like over-size ears. The letters on the keys look almost too big for the keys, like a baby animal with eyes too large for its head.

A slight and unassuming machine, the Corona XC-R nevertheless took on a heavy workload. Nick Block reports that the Corona XC-R was used by the Yiddish playwright Abish Meisels and the Jewish Daily Courier journalist Morris Indritz. Also, a Corona 3 XC-R, now kept by The National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, was used by Philadelphia correspondents for the New York-based The Jewish Morning Journal in the decades around WWII.

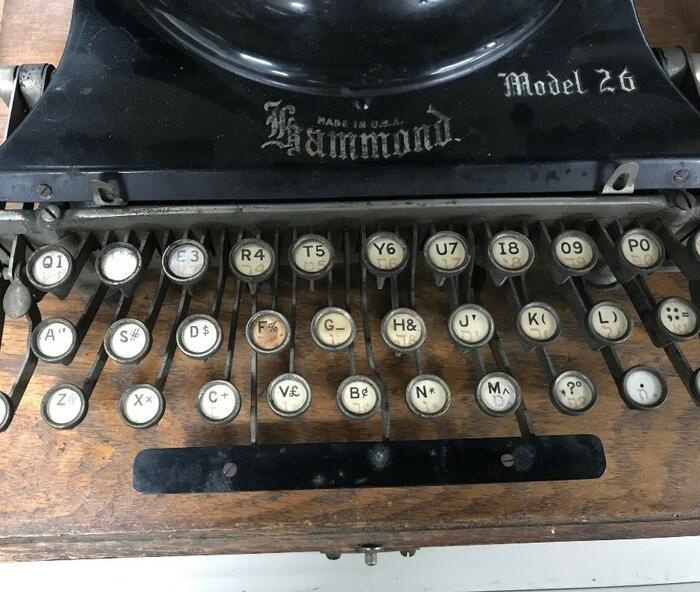

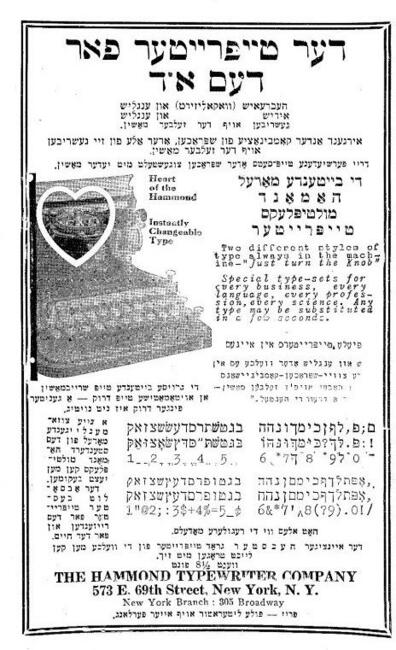

Trilingual and Full of Heart: the Hammond Multiplex

Year: between 1921 and 1927

Why to love it: it’s a linguistic and technological curiosity

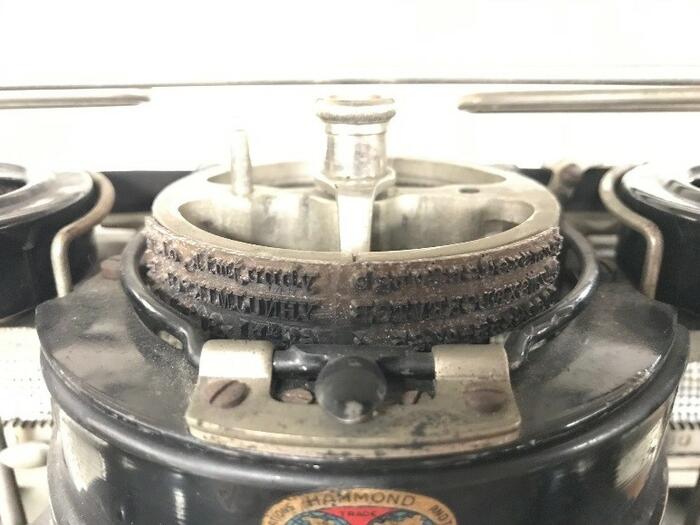

The Hammond Multiplex consistently garners “oos” and “ahhs” from Yiddish Book Center visitors. Unlike the Corona XC-R, its appeal lies in its complexity. Its sophistication comes from its trilingual keyboard (built for typing in English, Yiddish and vocalized Hebrew), and a special inner mechanism that switches between sets of type to produce all three languages. This inner mechanism works differently from most typewriters. Instead of pieces of type on individual levers hitting the paper, the Hammond Multiplex employs a round “swinging sector” covered in rows of type. In his book The Writing Machine: A History of the Typewriter, Michael Adler describes the mechanism, first designed in 1915: “Depression of a key first swung the sector to the corresponding character and then tripped a hammer located behind the paper; this struck it against the sector, with a rubber strip between the hammer and paper and a ribbon between the paper and type.” Turning a knob switches which row of type is positioned to be hit. As Sophia pointed out to me, the keyboard has phonetic correspondence between the Yiddish and English letters (“d” and “dalet” are on the same key, for example). Phonetic correspondence may have helped the typist to easily switch between languages.

The Hammond Multiplex

A 1922 advertisement for the Hammond Multiplex in Victor Mirsky’s Yiddish language periodical, The Jewish Almanac: A Year Book of Valuable Information, Chronology, and Statistics, highlights this new technology. Under the headline “The typewriter for the Jew,” the ad features an illustration of the Hammond Multiplex. The illustration has a heart drawn over the inner mechanism beside the words "Heart of the Hammond," encouraging the consumer to love the technology.

The advertisement also stresses the versatility of the Hammond Multiplex. First, the advertisement emphasizes the ease with which the type can be changed in order to switch languages. “Instantly changeable type,” it says, “Any or all language combinations, written on the same machine... Just turn the knob.” Next, the advertisement characterizes the Hammond Multiplex as a flexible professional machine: “special type-sets for every business, every language, every profession, every science.” Finally, the advertisement claims that the Hammond Multiplex is especially portable: “The absolute best typewriter for travel and for the home/ The only high grade typewriter of those that one can easily carry with oneself/ Weighs 8 ½ pounds.” It’s easy to imagine that for many new Jewish immigrants to the US, a practical, portable appliance with the ability to switch smoothly between languages (likely a constant issue in daily life) may have sounded appealing.

And yet, the “Typewriter for the Jew” was not for everyone: the trilingual Hammond Multiplex never became particularly popular. Adler attributes the decline of multilingual typewriters to falling typewriter prices, which allowed consumers to simply buy separate typewriters for each language. Call us old-fashioned, but we still heart the Hammond!

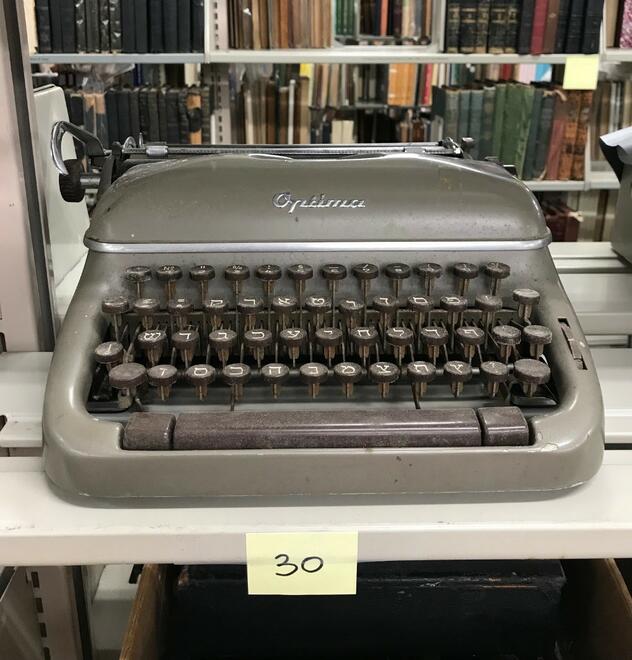

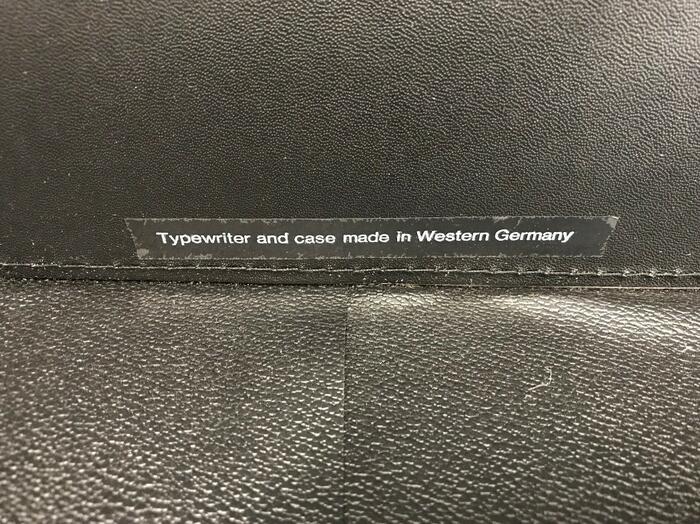

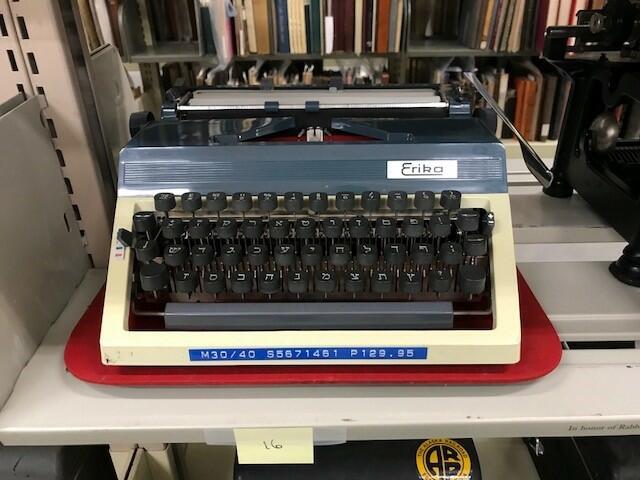

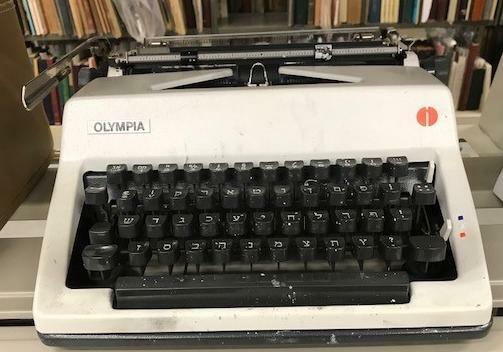

A Hebrew Typewriter from West Germany!?: the Olympia

Year: 1981 or 1982

Why to love it: it tells the story of German partition

This Olympia is the newest typewriter in our collection. Its white plastic frame and chunky keys, evocative of the recently created personal computer, may look silly. Nevertheless, the Olympia has an intriguing history. This typewriter was donated to us in 2016 by Eugene Driker of Washington, D.C., who told us that it once belonged to his Jewish History classmate, Rayna Kogan. While Eugene identified the Olympia as a Yiddish typewriter, the keyboard is actually designed for typing in Hebrew. This isn’t as contradictory as it sounds: while typing Yiddish on a Yiddish typewriter is more convenient, Hebrew typewriters were often used instead. Even Isaac Bashevis Singer used a Hebrew layout typewriter to draft his Yiddish masterpieces. By the time this Olympia was produced, it was likely easier to purchase a new Hebrew typewriter than a Yiddish one. All of the machines in our collection that were produced after 1951 are Hebrew typewriters, and it’s likely that they were all used to type in Yiddish at some point.

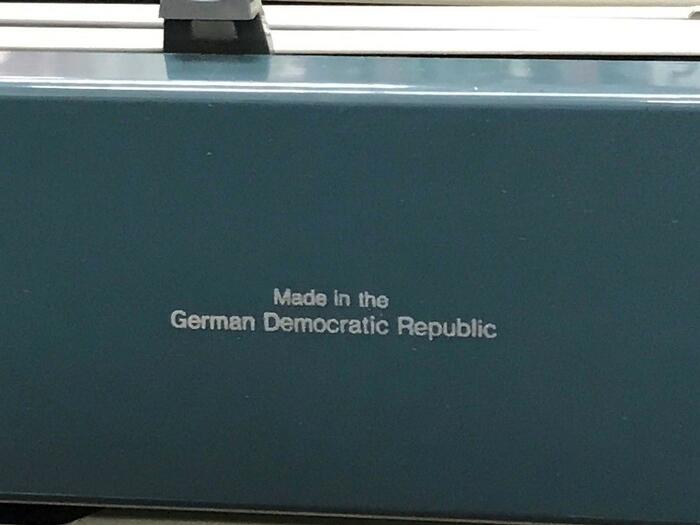

One of the first things that we noticed about the Olympia is the inscription on its case: “Typewriter and case made in Western Germany.” Once I had used its serial number to determine that the typewriter was built in 1981 or 1982, I became curious: Why was a Hebrew typewriter produced in West Germany in the early 1980s? I became even more curious after I examined another modern-looking Hebrew typewriter in our collection, an Erika from 1977 or 1978 and found an inscription on the back: “Made in the German Democratic Republic.” I later learned that two other typewriters in our collection, both Optimas made in 1960 or 1961, were also produced in East Germany. One of the Optimas has two inscriptions on the back: “Made in Germany” and “Germany USSR Occupied.” Why were all of these Hebrew typewriters produced in Germany, on both sides of the partition? And how and when did they travel to the United States?

While I have yet to answer either of these questions fully, I have learned more about the intertwined histories of the Olympia and Optima companies. According to a 2012 article by Robert Messenger, Olympia and Optima were originally the same company, called Olympia. In 1945, however, Olympia was split into two separately functioning companies by the Iron Curtain. Both companies used the Olympia name until a 1951 International Court of Appeal brand name ruling in the Hague made the split official. The company in West Germany retained the Olympia name and the company in East Germany became Optima. Because of the Iron Curtain, the two companies had different resources (Optima had fewer designers, for instance) and developed different designs as a result.

Hebrew Typewriters from Divided Germany

Writing in the Sun: Blume Lempel’s Remington Rand Deluxe

Year: 1948

Why to love it: it’s elegant and modern and was owned by Yiddish writer Blume Lempel

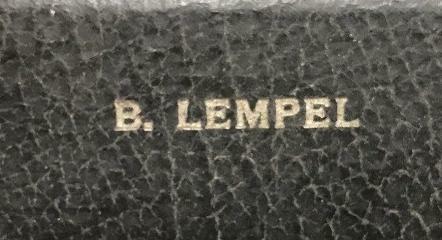

Finally, I’d like to present a very special typewriter. It’s a sleek and stylish Remington Rand Deluxe—a far cry from the Remingtons of the first few decades of Yiddish typewriters—owned and used by Yiddish writer Blume Lempel. The typewriter was donated to us just this past December by Lempel’s son, Paul, complete with a case embossed with “B. Lempel.” The typewriter was made in 1948, and Blume Lempel, living in New York City, received it as a gift from newspaper editor Pesakh Novick soon after.

Unlike the typewriters I’ve introduced to you so far, the smooth lines and sensible design of this Remington Rand Deluxe speak of a modern age. This beauty and modernity fit with the story of Blume Lempel: as described in a recent piece in Pakn Treger, Lempel found her voice as a writer in her middle age. The power of her stories impressed many established Yiddish writers, who mourned the fact that as a post-WWII Yiddish writer, her voice reached a tragically small audience.

When donating the typewriter, Blume’s son Paul explained that his mother set the typewriter in a sunny spot where she would write while Paul and his sister were in school. After listening to a recent podcast we produced about our typewriter collection, Paul wrote: “It brought back memory glimpses of my mother sitting at her writing table with the afternoon sun shining on her face, sometimes writing by hand and sometimes writing on the typewriter or sometimes just looking out at the passing world.” It’s amazing to think of Blume Lempel, sitting in the sun, bringing her words to light on her Remington Rand Deluxe. I became even more taken with this image when I found Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub’s translation of Blume Lempel’s short story “Shkheynim ibern ployt,” or “Neighbors Over the Fence,” published in the Winter 2013 issue of Pakn Treger. Like Lempel, Betty, the protagonist of the story, works at her typewriter and watches the world through her window during the school day. “When Betty is busy with a literary text,” the translation reads, “she loses track of time. Only when Mrs. Zagretti’s taxi appears does she realize she must put away her work before the children come home from school.”

Blume Lempel’s Remington Rand Deluxe is a prime example of how a Yiddish typewriter can tell its own story about Yiddish language, literature, and Yiddish speakers. Even when details linking a typewriter to a writer aren’t so readily available, a Yiddish typewriter can stir the imagination. Looking at or touching one of these typewriters, it’s easy to image the rest of the scene: a desk, table or countertop, a chair or bench, in a New York apartment, or perhaps a home in Montreal, maybe in the 1920s, or ‘30s or ‘40s. And then the life of the typewriter can be imagined: the initial admiration of the intricate and expensive machine, its everyday use for writing literature or journalistic pieces, poetry, letters. The hands that made it, sold it, typed on it, repaired it, stored it away in an attic. The typewriter’s sale, rental, or presentation as a gift, passed between owners many times, before falling into disuse, and then finding its way into our collection.

Thanks for taking the time to get to know the classic Remington 92, the sweet and simple Corona XC-R, the complex Hammond Multiplex, the unexpected Hebrew Olympia, and Blume Lempel’s elegant Remington Rand Deluxe. This is just a small sample of our (still growing) collection. I hope you’ll come take a tour of the full collection soon.

—Adah Hetko - 2018/2019 Yiddish Book Center Fellow

If you have a Yiddish typewriter that you'd like to donate please contact us at [email protected]