Subways, Skyscrapers, and Strikes: High-Schoolers Write about NYC

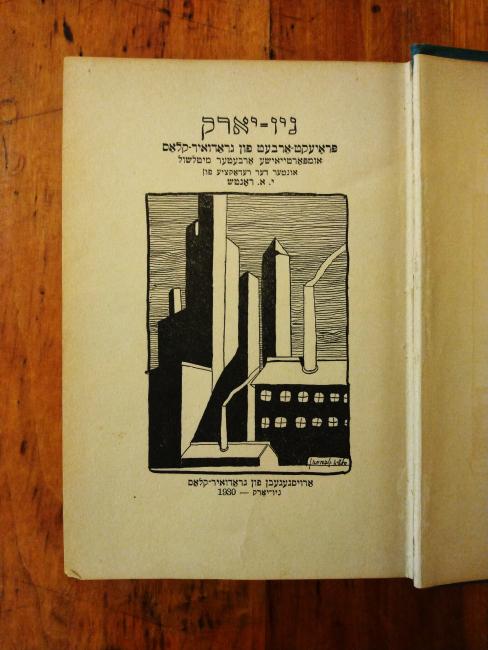

A self-published collection of essays on Depression-era New York City, put together by the 1930 graduating class of the Nonpartisan Workers’ High School in East Harlem.

“New York—a whirlpool. Elevated train, subway, skyscraper, labyrinths of streets, grotesque signal-towers; Bowery, Broadway, the Hudson—all have their charm and color. But the liveliest and most colorful are: the masses, that stream, making of the streets their vessels and bringing fast-pulsing life to the subways and skyscrapers.” So begins Sylvia Guberman’s chapter in Nyu-york: zamlbukh (New York: Anthology), a project by the 1930 graduating class of the Umparteyesher Arbeter Mitlshul, or the Nonpartisan Workers’ High School in East Harlem. Guberman was a typical student among her classmates—born in New York City to immigrant parents, sixteen years old at the time of publication, and devoted to secular Yiddishism. Later in her life, Sylvia Guberman published her fiction in such prestigious literary journals as Tsukunft (Future) and Di goldene keyt (The Golden Chain). But Guberman began her literary career with her “avant-garde” classmates in Yiddish and composition class, as her daughter, Dina Mann, recounts in her oral history.

The students wrote, edited, designed, and self-published the anthology with funds they raised themselves, under the guidance of their teacher, the writer Isaac Ronch. Each student selected a different topic to write about, from tawdry Coney Island thrills to the busy New York harbor to theater and politics and education. Their essays present a window into New York City in 1930, a time when the city was a center of industrial labor but also a time of crisis: “Around 700,000 workers are now unemployed in New York. The daily bread-lines on the Bowery bear witness to the great hunger and need in these laborers’ homes,” writes Priva Gluzman in her chapter on “Workers’ Life in New York.”

When this book was written, about 23 percent of Jewish children in the city were taught in Yiddish or Hebrew schools, and about 10 percent of these students were enrolled in secular Yiddishist workers’ schools. The Umparteyesher Arbeter schools were the most radical of them all, self-described as the “only [schools] struggling in a correct manner against bourgeois assimilation.” They gained their “nonpartisan” title by splitting off from the more widely-known Arbeter Ring (Workmen’s Circle) schools in the mid-1920s. The debates centered around loyalty to the Soviet Union and the older male leadership of the Arbeter Ring, as described by educator Hershl Hartman, although both schools shared an anti-Zionist stance and a commitment to social justice. There were thirty Umparteyesher Arbeter Sunday schools throughout Depression-era New York City and one high school in East Harlem, as well as a summer camp, Kinderland, which took in over 400 children every summer.

Courses at the Umparteyesher Arbeter Mitlshul included Marxist philosophy, history of workers’ movements, economics, and Yiddish-language courses and more general studies. In this era before Stalinist purges, the school was devoted to the Soviet Union, even sending student delegates to Moscow for a convention. The Nyu york book itself is written using a Soviet spelling system that intentionally de-Hebraicizes the Yiddish language, as a symbol of anti-clericism.

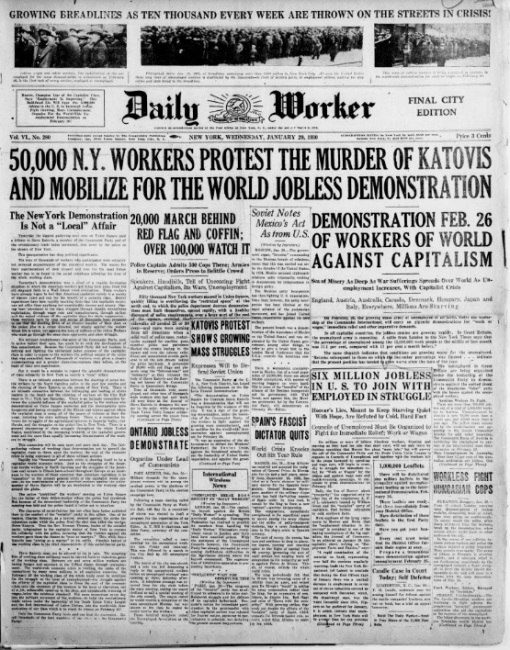

More than just admiring the Soviet Union, the student writers of Nyu-york: zamlbukh saw themselves as engaged in a revolutionary struggle to uphold its ideals in America. Their main opponent was the Tammany regime of the municipal government, including its strike-breaking police officers and conformist education system. The students had plenty of reason to feel as if they were at war. Just a few months before this book was published, a worker on the picket line was killed by a policeman, and his funeral turned into a mass demonstration of over 50,000 people. The students’ friends and peers were being expelled from schools and universities for distributing radical literature, and the dire conditions of the Depression made many believe a revolution was soon to come. Even the Yiddish press was implicated in this divisive battle. For the Umparteyesher Arbeter students, the Morgn frayhayt (Morning Freedom) was their newspaper of choice, while the more assimilationist Forverts (Forward) was thought to “appeal to the basest instincts among its readers.”

The 1930 graduating class of the Umparteyesher Arbeter Mitlshul identified a central paradox of immigrant life in New York in this era: How can a city with so many resources provide so little for its residents? As Sam Livovitsh describes in his chapter on education, “Rich New York is too poor to have enough room for its children . . . A strict discipline is instituted everywhere, a discipline of the whip. The teaching is mechanic, reminiscent of factories.” Then again, a tension also exists between the ideals of the students and the realities of workers’ lives in New York. For example, seventeen-year-old Itzik Garbaty praises the leftist Yiddish art theater of the Lower East Side but complains about the sparse crowds attending these pieces. Instead, theatergoers were much more likely to spend their hard-earned money on shund, or “trash”—theatrical pieces for a mass audience that were full of comedy, music, and melodrama. For all their talk of mass movements, these students were quite contemptuous of a mass culture they deemed as insufficiently revolutionary, even as most workers found solace and escapism in the shund theaters of Second Avenue.

Many of the students identify the need for Jews to unite with other races and nationalities in the struggle against exploitation, but prejudice and division took a bitter toll, especially the exclusionary racism of labor unions. In her chapter on immigrant enclaves in New York, Sylvia Ketsof walks us through the Syrian, Greek, Chinese, Italian, and Romani neighborhoods of the Lower East Side, as well as the internal migration of African Americans moving to Harlem. However, instead of a melting pot, Ketsof describes each neighborhood as a veltl, a tiny world unto itself, with its own defined borders within Manhattan’s grid.

Nyu-york: zamlbukh was written for a Yiddish and composition class, but the essays are not merely thought experiments. They represent the daily life and concerns of these students. In his essay on subways, Ben Levin describes the feeling of being on a packed rush-hour train, hearing scores of foreign languages spoken by exhausted workers. Levin captures at once the excitement and drudgery of the commute: “The crowd is horribly crushing, but you get used to it. It’s the same every day.” In another memorable essay, Esther Linetsky takes us on a tour of a sweatshop building in the Garment District. Unlike a typical journalistic exposé, with its air of objectivity, Linetsky’s account is strikingly personal. Her guide was one of her teenage friends working as a fur stretcher, who agreed to show her around the factory building on his lunch break. The air inside was stifling and the conditions were brutal. Esther was most shocked by seeing a group of young women painting numbers on clocks using radium paint. Although radium was known to be harmful at this time, the women were still putting the brushes in their mouths to smooth the bristles. As Esther Linetsky writes, “It’s remarkable how poverty can compel people—but also not so remarkable. Everybody wants to live.”

—Joseph (Khayim) Reisberg, February 2023

Joseph Reisberg is the 2022–23 Applebaum Family Fellow at the Yiddish Book Center. He was born and raised in Baltimore, MD, where he gained a love of pink flamingoes, and later studied history and creative writing and worked in the library at Goucher College. He had the joy of learning Yiddish for two summers with the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program at the Center. For an undergraduate thesis project, Reisberg translated poems by Rokhl Korn, whose lush imagery and deliberate choice to write in Yiddish first inspired him to learn the language.