Togbukh fun a veverke (Diary of a Squirrel)

A year in the life of a Yiddish squirrel from interwar Poland

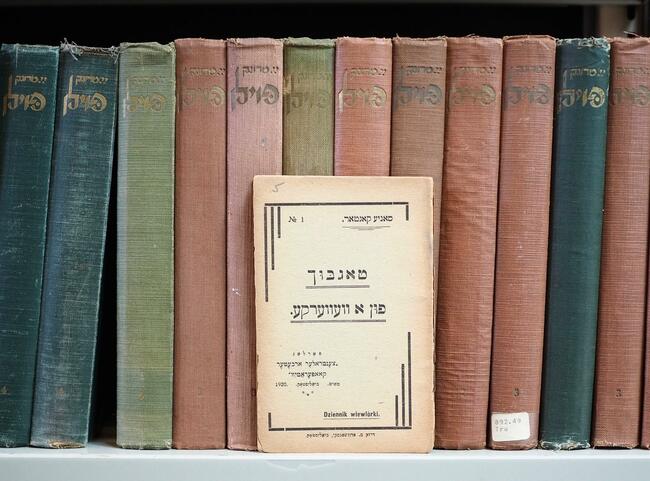

Little is known about the author Sonye (Sonya/Sonia) Kantor. Between 1920 and 1921, Kantor translated numerous stories by Ernest Thompson Seton (1860–1946) and Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) into Yiddish for the publisher Dos Bukh. Her translations of Seton are taken from his 1898 book Wild Animals I Have Known, and include tales of a crow, rabbit, cat, dog, and wolf. Her translations of Kipling’s stories contain more exotic animals such as a leopard, rhinoceros, and elephant. She also authored/compiled a work called In der melukhe fun morashkes un shvomen (In the Kingdom of Ants and Mushrooms). Both as a writer and translator, it seems children’s animal stories were Kantor’s specialty, and strangely, Kantor’s oeuvre is limited not only to this genre, but also to the years 1920–1921.

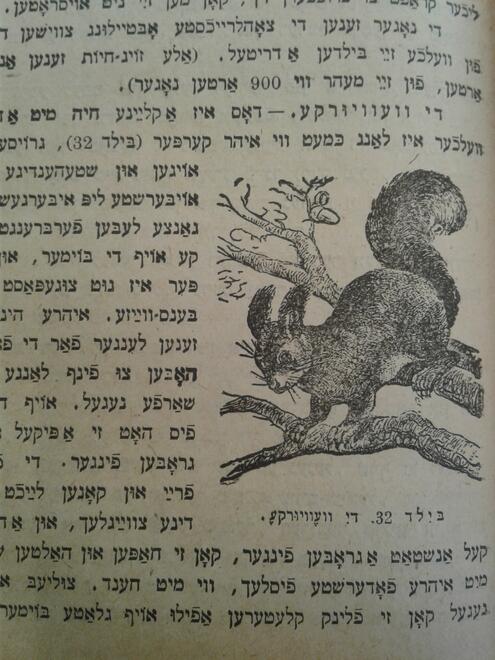

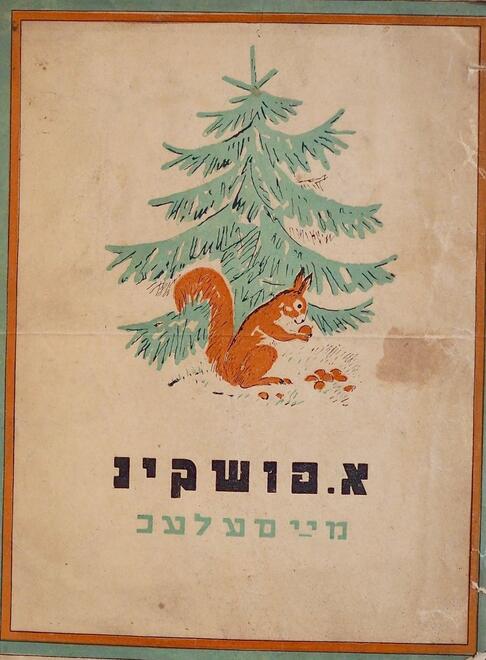

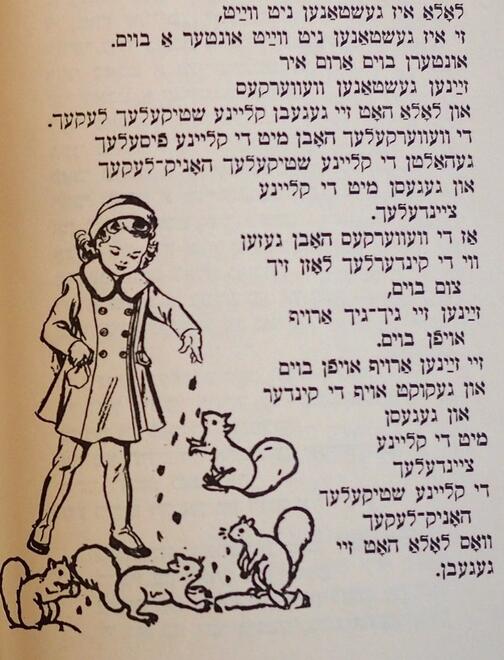

Kantor's Togbukh fun a veverke (Diary of a Squirrel) was published by the Tsentraler Arbeter Kooperativ in Bialystok, Poland in 1920. It begins with the end of spring, the narrator being a young squirrel living in a park with his mother, father, and younger sister, Lyubtshe. Life is good with lots of jumping and chasing. He and his sister learn to crack nuts and catch small animals. They tease each other with Lyubtshe calling him a knakerl (big shot) and him calling her a nasherke (snacker/someone with a sweet tooth). Both siblings are still small, however, and are wary of owls and martens.

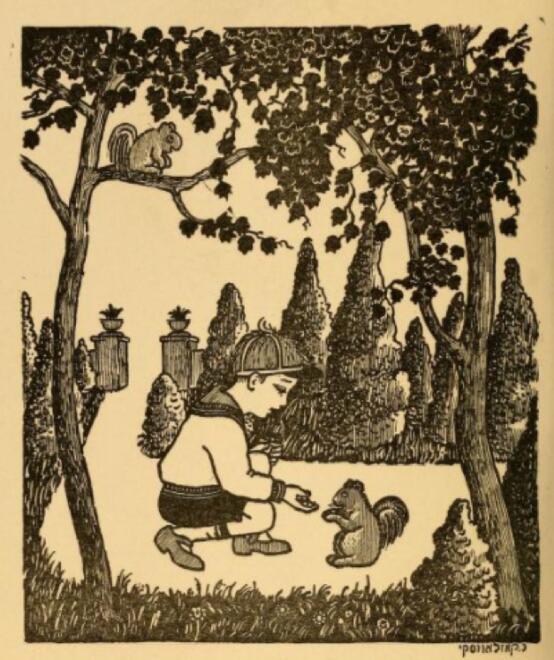

Summer brings on the heat, and both he and Lyubtshe continue to grow. They begin to wander farther from the nest and soon get to know their park and the other animals that live in it. Along the way, he has some (mis)adventures, including losing his way after his curiosity gets the better of him, a frightful experience with humans, and his first thunderstorm. As autumn approaches, greens give way to reds, oranges, and yellows—a joyous time, as nuts and seeds abound. But gradually it becomes colder and colder. The birds take off for warmer lands and he and his family frantically gather food for the wintertime, all except for Lyubtshe who continues to happily eat her findings.

When winter is due to arrive, the squirrel family moves to the forest, where they live with extended family and make new friends. In addition to his fellow squirrels, he meets a grey hare and a black raven. The first snowfall causes much excitement, but soon he and his family grow weary of the cold, which confines them to their nest for weeks on end. Eventually, sunbeams warm the earth, the birds return with their song, and flowers of all types and colors perfume the air. The family moves back to the park, only now our young squirrel has made a female friend and they build their own nest near his parents’. As spring enters full force, our narrator writes that he is now much too busy to continue to write in his diary. He is about to become a father.

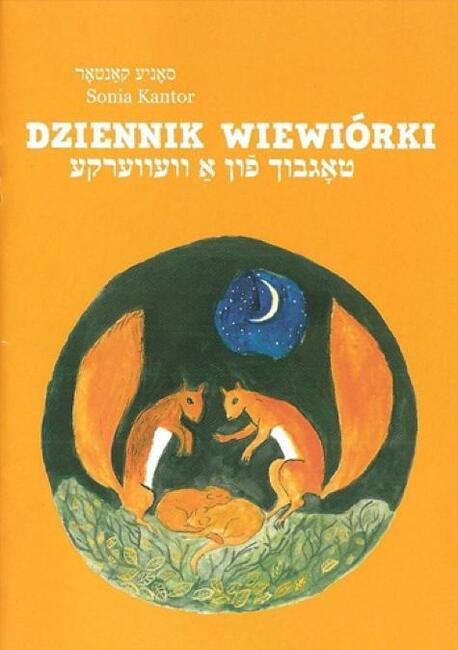

The story is told simply and is barely over twenty, tiny pages. (Tiny by human standards that is, quite large for a squirrel, in fact.) But there is something indescribably charming about this squirrel’s tale. The length suits it, as it is not so long as to bore a child, but provides enough depth to fully immerse a reader in the life of a squirrel. It contains beautiful descriptions of nature through every season. I reinforced my Yiddish vocabulary for types of nuts, trees, flowers, and animals. It’s quite unlike any other Yiddish book, and I was therefore excited to learn that this Yiddish-original has been revived in a new, bilingual Polish-Yiddish edition.

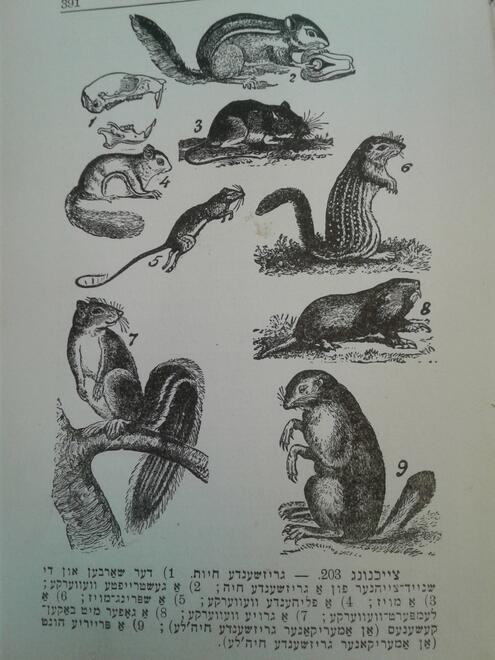

While I was happy to see that this wonderful book has a well-deserved following, I was curious to meet other squirrels in the Yiddish literary corpus. Yiddish children’s literature is full of animals; many birds fly onto the scene and even the occasional fish swims along. For land animals, those we invite into our homes and yards naturally get written into our literature too, and even the uninvited guests, such as mice, unabashedly let themselves in. Amongst forest animals, rabbits, bears, wolves, and foxes dominate. While more exotic animals from abroad captivate Ashkenazi youth.

But our nutty neighbors seem to be squirreled away in the nooks and crannies of Yiddish literature. From the aforementioned publisher in Bialystok, Dos Bukh, I managed to find a short story published in 1922 featuring a squirrel and a crow, available here. A few other squirrels make brief appearances in children’s stories or zoology books. But luckily for us, this little knakerl snuck out and wrote a diary for all to read.

—Elissa Sperling