Watching the (Yiddish) Detectives

When I think of “Yiddish” and “detective novel,” I think most immediately of Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. But, of course, there are actual Yiddish detective novels, and before there was Michael Chabon, there was Shlomo Ben-Israel (1910–1989).

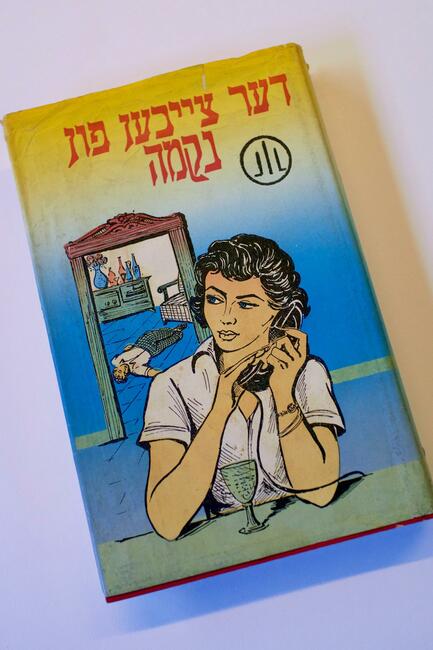

Ben-Israel penned Der tseykhen fun nekome (The Mark of Vengeance), a 1961 detektiv roman (detective novel) whose striking, vibrant cover caught my eye; it reminded me of Jewish-American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein’s signature style of illustration. The scene is dramatic, and everything is rendered in bright primary colors. A woman sits at a desk, cradling a telephone to her ear. She has a shifty look in her eyes and what looks like a kiddush cup before her. Behind her, there is a doorway through which we see a man’s lifeless body on the floor. The woman at the desk certainly doesn’t seem too concerned about the situation. Is she his killer? Whodunit?! You’ll have to read Der tseykhen fun nekome to find out.

Because Ben-Israel is a rather conspicuous name for a Yiddish writer, I was compelled to learn more about him. Shlomo Ben-Israel, it turns out, was born Shlomo Gelfer. His two names reveal his literary and linguistic tendencies: though a native Yiddish speaker, he wrote in Hebrew as well as in Yiddish. He was inspired by Haim Nahman Bialik. He wanted to create a voice for himself in Hebrew fiction, and ultimately became known for his fictionalized mystery stories about David Tidhar, “the Sherlock Holmes of the Yishuv.” In 1939, he emigrated from Palestine to the United States, where he had a career as a journalist in the Yiddish press: he was a staff writer at the Yiddish Forverts and a radio commentator for WEVD, a Yiddish radio station.

The novel is pulpy and fast-paced, with descriptive chapter titles that are at turns opaque and revealing, like “The Shidekh,” “The Woman Behind the Door,” “The Small Man with the Inky Finger,” “Yermiyahu Flees to Israel,” and “The List of the 36.” The table of contents alone alludes to multiple different doctor characters: Dr. Dietrich, Dr. Brenzo, and Dr. Vellinger. This is a novel that has more in common with Raymond Chandler than Isaac Bashevis Singer, more Arthur Conan Doyle than I. L. Peretz.

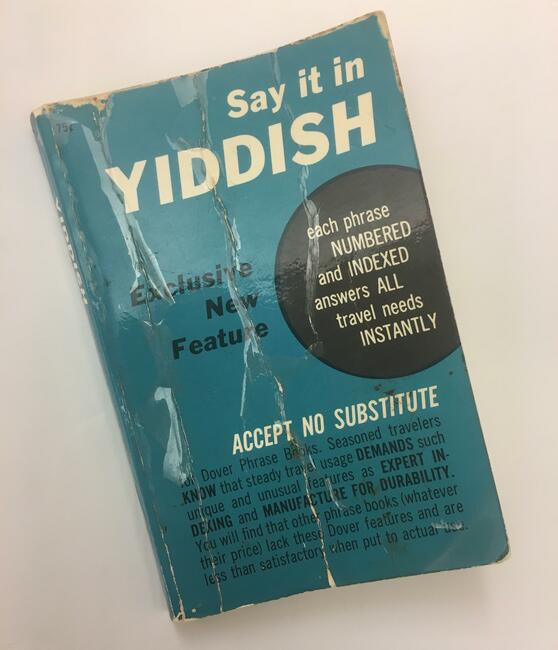

Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union is based on the premise that a Yiddish-speaking Jewish colony was temporarily established in Sitka, Alaska in the mid-twentieth century. (Sitka “sounds kind of Yiddish,” Chabon said.) An upcoming “Reversion” threatens the colony’s autonomous status. It is a counterfactual history novel in the style of Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America. It draws upon classic hardboiled detective fiction, raises questions about diaspora identity, and, in my opinion, ranks among the most important Jewish-American novels of this century. But for a Yiddishist, the story is complicated. It was inspired by Chabon’s incredulity at a 1958 “Say it in Yiddish” phrasebook, written by famous Yiddish scholar Uriel Weinreich. After stumbling across this book, Chabon wrote about it in a controversial essay expressing his disbelief in the utility of such a book in the postwar era. He called it “the saddest book I own,” believing it to be an “absurd, poignant artifact of a country that never was.” “I’ve never been there,” he wrote. “I don’t believe that anyone has.” The essay was not well-received by Yiddish speakers and scholars, and to his credit, Chabon later apologized for his ignorance: of course, there were millions of Yiddish speakers who conducted their lives in mame-loshn, and theirs was not some rarified lifestyle in which they had no use for mundane phrases.

References to aspects of yiddishkayt abound in unexpected places: Chabon’s Alaskan Jews, the “Frozen Chosen,” smoke papirosn, drink slivovitz, play pinochle, stroll down Zhitlovsky Avenue, and visit Czernovitz Island. Yiddish enters American diction in strange, imaginary ways: a “latke” is a beat cop; a “sholem” is a gun (a clever play on the colloquialism “piece,” because sholem means “peace”); a “shammes” is a detective; a “shtarker” is a gang member.

For lovers of Jewish culture, it is singularly enjoyable to read a novel peppered with Yiddish Easter eggs (afikomens?). But by this same token, it reveals Chabon's shallow knowledge of Yiddish in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust. This culture was not the stuff of counterfactual fiction; on the contrary, Yiddish culture was alive, not only in the shtetls of the past, but in corners of New York City, Paris, Tel Aviv, and the other metropolitan centers where refugees settled. It is the same unfamiliarity that made Chabon find Weinreich’s phrasebook absurd. The Yiddish Policemen’s Union is cute and clever and kitschy, but by locating yiddishkayt within a counterfactual utopia, it erases the reality of Yiddish culture.

For lovers of Jewish culture, it is singularly enjoyable to read a novel peppered with Yiddish Easter eggs (afikomens?). But by this same token, it reveals Chabon's shallow knowledge of Yiddish in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust.

Yiddish does not need Chabon’s “sholems” and “latkes,” because it already has pistoyln and politsey. To create a Yiddish speaking world in English, with cutesy smatterings of repurposed Yiddish throughout, is to deny the truth of Yiddish as a modern language, with a robust vocabulary that evolved with the times—even a specific vocabulary for crime fiction. Isaac Bashevis Singer’s claim in his Nobel lecture that Yiddish was “a language which possesses no words for weapons, ammunition, military exercises, war tactics,” was an act of fantasy. Yiddish already has its own words for “guns” and “policeman” and “detective.”

Many of these critiques have already been leveled at Chabon’s book, and I do not want to beat a dead horse, nor to criticize a genuinely great book. Chabon’s novel is genius in its own way; it is absolutely worth reading and contending with, particularly if you are not wont to get riled up about Yiddishist politics. Even if Chabon’s premise, that modern daily life in Yiddish was, by nature, counterfactual, was misguided, it nonetheless gave rise to a worthwhile work of art. But it illustrates an important point, of which Der tseykhen fun nekome is Exhibit A—people who spoke and read and wrote in Yiddish spoke and read and wrote about all manner of things; their tastes and interests were as diverse as the tastes and interests of the speakers of any language.

In writing The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Chabon was superimposing his version of yiddishkayt onto what he may have believed to be a separate, unrelated genre, but there was already a tradition of real Yiddish detective fiction. Yiddish words with English-language recognition do not need to be repurposed in order to tell a Yiddish detective story; those words already exist, and so do those stories.

—Miranda Cooper