Weekly Reader Ukraine

March 3, 2022

The long and complicated history of Jews in Ukraine was not always a happy one, but it would be a mistake to think of it as an unmitigated series of pogroms and tragedy. To the contrary, the region gave rise to some of the greatest achievements of Jewish literature and culture, as the collections of the Yiddish Book Center bear witness. At this moment, with Ukraine under attack and its people and their Jewish president fighting for their very survival, we remember our shared history and highlight some of the enduring creations of Yiddish-speaking Jews in Ukraine.

—Ezra Glinter

A Conference in Chernovits

In 1908 Jewish intellectuals from across Europe gathered in the city of Chernovits—or Chernovitsi, in Ukrainian—to determine the future of the Yiddish language. Although the stated purpose of the First Yiddish Language Conference was to elevate and standardize the language, thus furthering its literary and cultural ambitions, the gathering nearly got derailed by a fierce dispute about the status of Yiddish relative to Hebrew. Was Yiddish “a” Jewish national language or “the” Jewish national language? In the end, the indefinite article won out.

Read about the First Yiddish Language Conference

From Cabbages to Galaxies

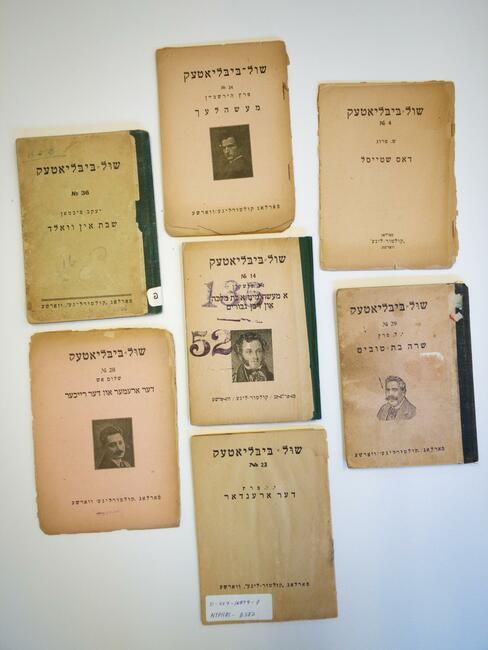

At the beginning of 1918, the first Kultur-lige (culture league) was formed in Kyiv with the goal of promoting and developing contemporary Yiddish culture. By the end of the year, the organization had seven sections: literary, educational, publishing, library, musical, theatrical, and artistic. Within two years there were 99 branches with 283 institutions across Ukraine, and Kultur-lige’s publishing houses became the main producer of Soviet Yiddish books. But even more impressive than the sheer volume of the publisher’s output was its wide-ranging subject matter, stretching from classic Yiddish authors to atomic physics.

Read about the history of the Kultur-lige

Leaving Home

Chone Gottesfeld was born in 1890 in Skala-Podilska, where he spent his childhood years attending heder. As a teenager, Gottesfeld studied in Chernovits and Vienna before immigrating to the United States at age eighteen. In his memoir Vos ikh gedenk fun mayn lebn (What I Remember of My Life) he recounts his journey to America and the overwhelming homesickness he felt as the train pulled out of his Ukrainian hometown. At once humorous and bitter, judgmental and sympathetic, Gottesfeld’s recounting of his journey to America immerses the reader in the feelings of the teenaged traveler.

Read an excerpt from Chone Gottesfeld’s memoir translated by Sophia Shoulson

A Standup Guy

Sholem Aleichem, perhaps the best-loved Yiddish writer in history, was born in Pereiaslav, a town near Kyiv, and spent his formative years in the cosmopolitan center. Today, Kyiv boasts a statue of the writer right in the center of town. In an interview with the Wexler Oral History Project his granddaughter, Bel Kaufman (herself an accomplished novelist, best known for Up the Down Staircase) recalled her early memories of her grandfather, including his penchant for writing at a standing desk.

Watch an oral history interview with Bel Kaufman

The Immigrant Intellectual

Born in Yarmolinetz (Yarmolyntsi, in Ukrainian) in 1883, Abraham (Ab) Goldberg was a prolific writer, journalist, and public figure in labor Zionist circles in New York. In his 1924 essay “The Immigrant Jewish Intellectual,” Goldberg explores the alienation felt by those cut off not only from their homeland but also from their family, friends, and compatriots, all of whom are also dealing with the struggles of isolation in overlapping ways. Goldberg compares the plight of the immigrant Jewish intellectual in America with that of Robinson Crusoe, a comparison that does not go well for the intellectual.

Read a translation of “The Immigrant Jewish Intellectual” translated by Daniel Kennedy

Fields of Song

In this oral history interview, Polina Markovna Shepherd, a Yiddish performer, composer, and choir leader, recalls her experience as a performer at a music festival in Ukraine. She describes the proud Ukrainian atmosphere of the events and teaching nigunim in a field near the origins of nigunim themselves.

Watch an oral history interview with Polina Markovna Shepherd