Weekly Reader: A Bittersweet Time

The end of Sukkos is a bittersweet time. The holiday, by its nature, is a happy occasion. It’s a harvest celebration (always a party) and, according to tradition, the most joyous time of the year. For all the joy, however, there is sadness. After the cascade of fall holidays, there are no more until Hanukkah. (No more Jewish ones, at least.) In the northeastern United States where the Yiddish Book Center is located, we may be enjoying the brilliant fall foliage, but winter is coming. For Yiddish-speaking Jews this bittersweetness, a combined sense of beginning and ending, of renewal and senescence, has been amply expressed in literature and art. Here are a few of our favorites.

—Ezra Glinter

Sukkos with Sholem Aleichem

What would be a Jewish holiday without an accompanying story by Sholem Aleichem? This most beloved of Yiddish writers covered every occasion on the calendar, and Sukkos is no exception. In the ninth volume of his collected works you can find his children’s story “Once Upon a Sukkah,” written in 1906. And if you’re looking for something in English, there’s an original translation by Curt Leviant of his story “The Esrog,” about that most fragrant yet fragile fruit.

Read Sholem Aleichem’s “Once Upon a Sukkah” (in Yiddish)

Read Sholem Aleichem’s “The Esrog” (in English)

Modern Autumn

The modernist writer Blume Lempel seems to have emerged only in the autumn of Yiddish literature. “It is enough to make one weep, that you appeared in our literature at a time when so few good readers remained,” Chaim Grade wrote to her. “But perhaps it could not have been otherwise. Perhaps your magical, sweet, lyrical tone could not have come into being any earlier than our autumn years …” Yet, as translators Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub argue, “the ‘autumn years’ of Yiddish literature were not the end of the road for Blume Lempel. Today she is finding a new readership, in English, in another era—our own.”

Read an essay about Blume Lempel

A Sukkah Full of Memories

Sukkos evokes fond memories for many people. Whether it’s the season or the unusual circumstance of eating outdoors in a leaky hut, many Jews look back on their Sukkos experience with wistfulness, and perhaps a touch of nostalgia. Here, four different narrators share memories of Sukkos and of their families’ sukkahs. For Mikhl Yashinsky, theater artist and Yiddishist, his family’s sukkah was a symbol of their “American Yiddishkayt.” Ingrid remembers her uncle’s annual sukkah in the Bronx and how, on windy days, he would invariably have to chase it down the street.

Watch four narrators reminisce about Sukkos

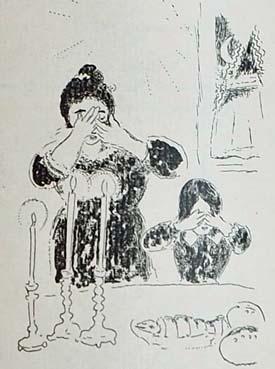

Yontev with the Chagalls

When Bella and Marc Chagall chose to collaborate on the book Brenendike likht (Burning Lights), a tribute to the town of their youth, Bella deliberately chose Yiddish as its language. “It is an odd thing,” she wrote. “A desire comes to me to write, and to write in my faltering mother tongue, which, as it happens, I have not spoken since I left the home of my parents.” In this exercise from the Yiddish Book Center’s textbook In eynem, Bella narrates a Sukkos observance from her childhood, accompanied by an illustration from her husband.

Learn about Bella Chagall’s Sukkos in Vitebsk

Fall Song

What would fall be without Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman’s “Harbstlid” (“Autumn Song”)? It is certainly the best-known, and one of the most beautiful, works by the great Yiddish poet and songwriter, who died in 2013. In this oral history interview you can hear Beyle’s granddaughter Esther talk about her relationship with her grandmother’s music, and with “Harbstlid” in particular. Of course, we have a full-length interview with Schaechter-Gottesman herself, in Yiddish with English subtitles. And if you’ve never had the pleasure of listening to “Harbstlid,” well—YouTube will help you out.

Watch an oral history interview with Esther Gottesman

Watch an oral history interview with Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman