Weekly Reader: Here's to Zalmen Reyzen

There are only a few authors whose work every Yiddishist knows. The three “classic” writers—Mendele Moykher Sforim, Sholem Aleichem, and I. L. Peretz—are surely among them. Then there’s Zalmen Reyzen. Reyzen, whose birthday would have been this month, was a newspaper editor and a founder of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, but his greatest claim to fame is his monumental four-volume Leksikon fun der yidisher literatur, prese, un filologye, a biographical dictionary of Yiddish literature, press, and philology. Similar biographical dictionaries exist in other languages—in English we have the 375-volume Dictionary of Literary Biography—but in Yiddish they are especially precious given the scant information we have on many Yiddish writers. It’s no exaggeration to say that Reyzen’s work is used regularly by every Yiddish researcher in existence. So here’s to Zalmen Reyzen, and the Yiddish biographical dictionaries he pioneered.

—Ezra Glinter

Straight to the Source

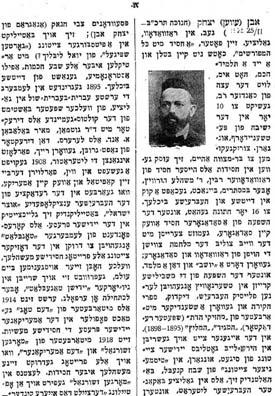

We of course have to start with Reyzen’s Leksikon itself. As befits such a monumental work, the Leksikon went through multiple iterations and editions, starting with the Biographical Dictionary of Yiddish Literature and Press, which was published in 1914. You can find that on our website, but here we’re going to highlight the first volume of the more canonical 1926 edition, published in Vilna by B. Kletskin. And while we’re not going to bombard you with every single leksikon we have in our collection, you can find them easily enough with a little poking around.

Read the first volume of Zalmen Reyzen’s Leksikon

Family Affair

Zalmen Reyzen wasn’t the only Reyzen out there, or even the most famous. His older brother Avrom probably gets that title, thanks to his long and illustrious career as a writer of fiction. His sister Sore Reyzen, though less recognized than either of her brothers, was a poet, prose writer, and translator in her own right; she translated works by Pushkin, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Tagore, and Defoe into Yiddish. Interestingly, she was also an agent of sorts for her brothers’ literary careers, negotiating with Warsaw editors and publishers on their behalf. Her letters, translated here by Ri J. Turner, reveal a commanding personality and an intimate familiarity with the Yiddish publishing scene.

Read a selection of Sore Reyzen’s letters

A Controversial Canon

As with all canonizing activities, Reyzen’s Leksikon was accompanied by its share of controversy, especially in its earliest days. In particular, some naysayers complained that Reyzen and his coeditor, the literary critic Shmuel Niger, had overlooked a number of younger writers. While it’s unlikely that a protest march of Yiddish writers—much less a riot—actually took place, there is little doubt that many writers were upset about having been left out of Yiddish literary history.

Read about the controversy surrounding Reyzen’s Leksikon

The Sincerest Flattery

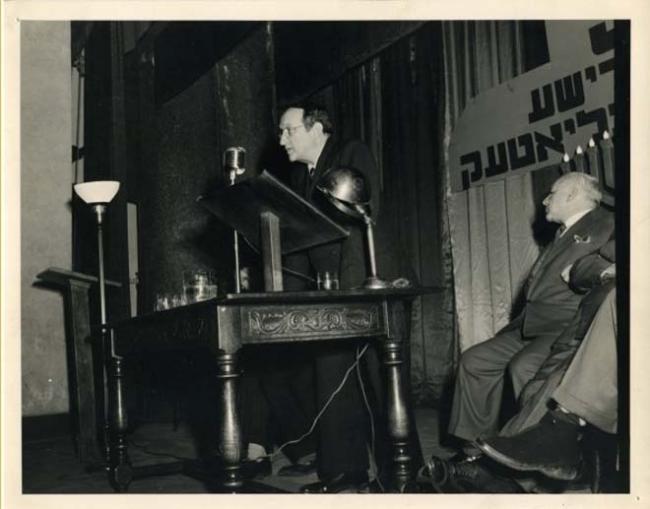

Reyzen’s Leksikon was the first effort of its kind in Yiddish, but it was hardly the last. After Reyzen followed his initial 1914 Leksikon with its four-volume successor, he was followed in turn by the eight-volume Leksikon fun der nayer yidisher literatur (Biographical Dictionary of New Yiddish Literature) and the six-volume Leksikon fun der yidisher teater (Biographical Dictionary of the Yiddish Theater). There have also been more idiosyncratic entries in the category, including Melech Ravitch’s Mayn leksikon, based on his own relationships with Yiddish writers and their works. In this priceless recording from the collections of Montreal’s Jewish Public Library we can listen in on the 1958 publication party for that volume.

Listen to the Montreal premiere of Mayn leksikon

A Rich Legacy

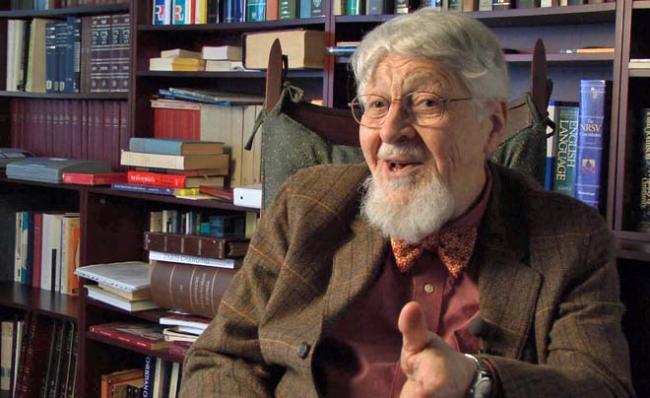

Reyzen is best remembered for his Leksikon, but he was involved in many different literary and cultural activities, including his role as a founding member of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Among his peers was the person most closely associated with YIVO in its early years, linguist Max Weinreich. In this oral history interview, Gabriel Weinreich—professor emeritus of physics, Episcopal priest, and son of Max—remembers how his father occasionally looked after him in his YIVO office.