The Weekly Reader: Jewish artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

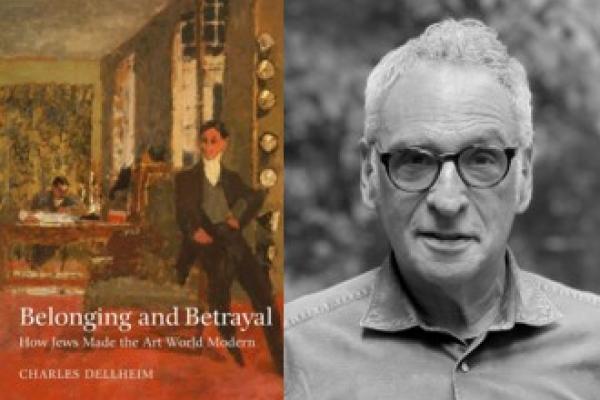

When it comes to Yiddish-speaking artists—and Yiddish modernists in particular—everybody knows about Marc Chagall. But what about other Jewish artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? And not just the artists but also the collectors, dealers, and patrons who made their work possible? Was there such a thing as a Jewish art world? On February 2 author Charles Dellheim will present a virtual public program on How Jews Made the Art World Modern, a look at Jewish outsiders who played a critical role in modern art as dealers, collectors, critics, and, not least, as artists. To whet our appetites, here are a few things to read in advance.

—Ezra Glinter

Bohemians of Montparnasse

This might very well be the biggest book in the Yiddish Book Center’s collection, physically speaking. Bilder un geshtaltn fun montparnas (Scenes and Figures of Montparnasse), by Polish-Jewish art critic Chil Aronson, is a monumental tome, about the size of a small suitcase. It offers a unique perspective on the École de Paris—the extraordinary constellation of Jewish artists who flocked to Paris in the early decades of the twentieth century. Published in 1963 and never translated, it remains inaccessible to most art historians. Someone may yet undertake that project, but in the meantime, we hope these excerpts will prompt renewed interest in this forgotten classic.

Read about the Bohemians of Montparnasse

Read Aronson’s book in the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library

Can Art Be Yiddish?

Critics and scholars often talk about Yiddish writers—but what about Yiddish artists? Can we attach a language to visual arts? This is a question that the multitalented, multimedia artist and critic Saul Raskin might ask. Born in Nogaisk (now known as Prymorsk, in southern Ukraine) in 1878, Raskin studied lithography, painting, and drawing at art schools in Odessa, Berlin, and Paris before immigrating to the United States in 1904. His work is incredibly diverse: he wrote travelogs, art books, and even a mystical novel, the evocatively titled An oysgetrakhter emes (An Invented Truth). Many other books bear his mark in some form: his typography adorns their covers; his illustrations add life to their pages.

Read about Saul Raskin and the question of Jewish art

Avant-Broadway

Boris Aronson was a Broadway set designer who won the Tony Award six times. But before he made it to Broadway he got his start in avant-garde Yiddish theater in Kyiv. In this oral history interview Boris’s son, Marc Aronson, discusses his father's life in the art world of Europe, including his participation in the Kultur lige (Culture League) in Kyiv, his work on a book about Chagall, and his involvement in the cabarets of Berlin. He also discusses his father’s exploration of his own identity and where his Jewishness fit into broader national identities.

Watch an oral history interview with Marc Aronson

At Home with Marc and Bella

When it comes to modern Jewish art Marc Chagall might be a bit on the nose, but we can’t leave him out altogether. Here’s a side of Chagall that you might not have seen, however: his wife Bella’s Yiddish memoir, Brenendike likht (Burning Lights). It features illustrations by—who else?—her husband.

Read Bella Chagall’s Brenendike likht in Yiddish

View reading resources for the 1946 English translation of Burning Lights

Recovered Loot

The Nazi plunder of Jewish art collections is a well-known fact. Still, it has taken decades to recover those stolen artworks, and some of them have never been returned. Last year The Jewish Museum in New York did an exhibit dedicated to those collections titled Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art. The exhibit is now over, but you can listen to an episode of The Shmooze podcast with curator Sam Sackeroff and hear about the seizure and movement of artworks as they traveled through distribution centers, sites of recovery, and networks of collectors before, during, and after World War II.

Listen to a podcast episode about stolen artworks