Weekly Reader: The World of the Writers

May 22, 2022

At the Yiddish Book Center, we do a host of different things: lectures, classes, exhibitions, concerts . . . if it has to do with Yiddish, chances are you’ll find it here. But every so often we like to take a step back and remember the fundamental reason for our existence: the thousands upon thousands of Yiddish books, often rescued from dumpsters, that fill our shelves and website for this generation and every generation to come. And while we’d like to take some credit for helping to preserve these books, we’d be nowhere if not for the thousands of Yiddish writers who made them and gave us this precious legacy in the first place. So this week we’re going to get back to basics and take a moment to reflect on those writers and the world they and their books created.

—Ezra Glinter

A Writer's Advocate

Yiddish-speaking immigrants to the United States were front and center within the American labor movement, and its writers were no exception. Still, the early days of the I. L. Peretz Yiddish Writers’ Union were “not entirely a bed of roses,” as Hillel Rogoff, a Forverts editor and the union’s first president, told an interviewer from the magazine Labor Age in 1922. But by the time of that interview, seven years after its founding, the union claimed two hundred members and had secured for its workers benefits such as a six-hour workday and a minimum wage of $60 a week—“though the great majority receive much more than that.”

Read about the Yiddish Writers’ Union

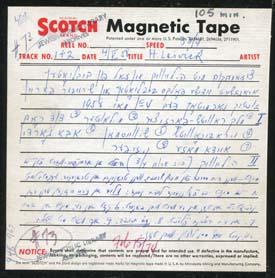

An Afternoon Meeting

When we undertook to organize and digitize the entire audio archive of Montreal’s Jewish Public Library, we knew that we would find countless treasures among its many decades of public programming. Practically every Yiddish writer alive after 1953, when the archive begins, shows up among the recordings. Still, every so often we come across something that stuns us with its historic and cultural interest even if—and sometimes especially if—it seems rather mundane. Take, for example, this recording of a 1958 afternoon meeting of the aforementioned Yiddish Writers’ Union, led by the famed poet H. Leivik just a few years before his death.

Listen to “An Afternoon Meeting with the Writers Union”

Her Brothers' Agent

Sore Reyzen is perhaps best known as the sister of Avrom Reyzen, a prolific Yiddish poet and short story writer, and Zalmen Reyzen, compiler of the Lexicon of Yiddish Literature, Press, and Philology, one of the most important Yiddish reference works. But Sore was also a poet, prose writer, and translator in her own right, and she was heavily involved in negotiating with Warsaw editors and publishers on her brothers’ behalf. Her letters reveal a commanding personality and an intimate familiarity with the Yiddish publishing scene, and they are studded with casual mentions of the stars of Yiddish literature.

Read a selection of Sore Reyzen’s letters

A Rich Brew

The introduction of public coffeehouses to the capitals of Europe helped create the Enlightenment and the modern world in which we now live. But what effect did they have on Jewish culture? Shachar M. Pinsker’s book A Rich Brew: How Cafés Created Modern Jewish Culture tells the story of the coffeehouses’ central role in the modern Jewish experience during a time of migration and urbanization—from Odessa, Warsaw, Vienna, and Berlin to New York City and Tel Aviv—and why Jews became their most devoted habitués.

Listen to an interview with Shachar M. Pinsker

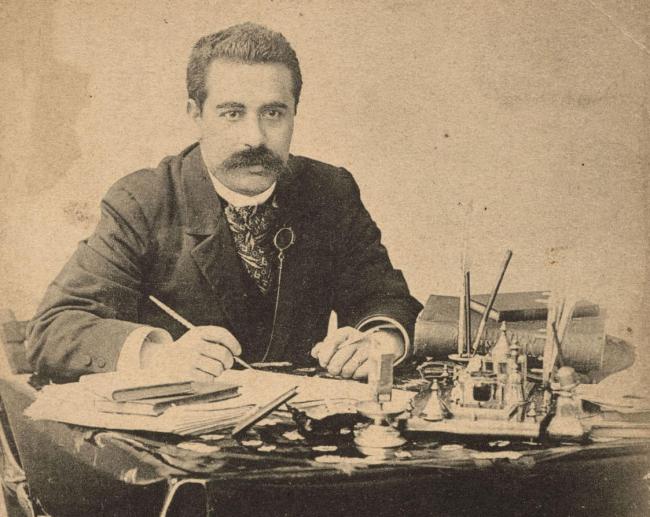

Man and Myth

There is no more important figure in the history of modern Yiddish literature than I. L. Peretz. In addition to his own formidable body of work, he served as a mentor to a whole generation of Yiddish writers whose biographies, more often than not, include a fateful encounter with Peretz at one point or another. But unlike some other major Yiddish writers, Peretz has been poorly served by posterity. Sholem Aleichem feels familiar, if only from Fiddler on the Roof. Bashevis Singer’s fascination with human frailty chimes with our modern sensibility. By contrast, Peretz, whose personal charisma fascinated his contemporaries, remains an enigma.