The Curse

From "My Father's Tavern" by Yitzkhok Horowitz, Translated by Ollie Elkus

Born in 1894 in Romania, Yitzkhok Horowitz was a little-known Yiddish translator, editor, belletrist, and children’s playwright. After immigrating to the United States in 1909, Horowitz published a slew of children’s plays throughout the 1920s, a decade which culminated with his most well-known published work, a Yiddish translation of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, in 1929. He later became a writer for The Forverts, and in 1953 his memoir Mayn tatns kretshme (My Father’s Tavern) became his final published work before his death in 1961 at the age of 67.

In My Father’s Tavern, Yitzkhok captures the world of fantasy and superstition that was his village in eastern Romania at the turn of the twentieth century. Organized as a collection of vignettes, each chapter depicts an aspect of rural Romanian life or an anecdote from Yitzkhok’s youth, all of which take place in or around his father’s tavern. Much to the dismay of Yitzkhok’s mother, the Horowitzes were a lone Jewish family living among Gentiles. This was uncommon in the old country, but Yitzkhok’s father was something of a Romanian war hero and therefore allowed to settle in the village of Popricani. This unique post-shtetl upbringing makes for tales of personal Jewish-Gentile relationships both tense and touching, with nuance not found in most literature from the Pale of Settlement.

Among Yitzkhok’s more whimsical subjects are the staple ghouls, ghosts, and goblins of Yiddish folklore, which haunt the basement of the tavern. Other chapters feature tales of traveling Roma, the 1907 Peasants’ Revolt, and real-life run-ins with forest wolves. But in this world of fantasy and superstition, only a few stories emerge to be the most fantastic and superstitious. One such example is chapter eight, “The Curse,” which also proves a most colorful depiction of the tavern, of Yitzkhok’s father, and most of all, of a strange man named Răşcanu . . .

***

Our Sundays in the tavern, cheerful though they were, would often end in a fight. It would usually break out in the afternoon, when the peasants were dead drunk. If my father suspected a fight, he would have us cart the bottles and glasses off the tables and clear the empty crates and scraps of wood and iron that were lying around the tavern and might be of use to the combatants in their fit of rage.

The fight would start discreetly, almost unnoticed. At one of the tables two drunken peasants would trade curses. This was considered completely normal, so nobody would pay any mind. But soon the two men would jump from their seats and start flailing their arms. From slaps it would escalate to fists, and from fists to sticks. This is when the real fight would begin. Since the sticks were bound to hit another peasant, and insofar as the whole village was kith and kin through varying degrees of familial relation, one would stick up for another, and another for another, and soon the whole village would be mixed up and mired in a full-fledged fight.

My father had a method of suppressing the nightly row. When he saw that it was getting out of hand, he’d order us to extinguish the lamp. In the darkness no one could tell who was hitting who. You could only hear the wild war cries of the beaters and the moans and whimpers of the beaten. And as soon as a son heard the moan of his own father, or a husband recognized the whimper of his wife, the fighting would stop. But these were scuffles. One couldn’t stop a great brawl. And it was always a great brawl when Răşcanu was involved.

***

Răşcanu was a strapping young peasant, built tall and sturdy. He had big cheekbones and beady eyes. Because of his bravery and fine attire, in the village they called him “Hajduk,” a reference to the well-dressed bandits and freedom fighters of the Balkans. He wore a large black hat with a wide brim and a long woven tassel at the side. His shirt was embroidered with the loveliest flowers and blossoms, and instead of the more typical woolen belt he wore a wide leather chimir, a girdle adorned with yellow spangles and colorful beads. Even his corded money pouch that protruded from his chimir was decorated with beautiful beads. But what made him look like a Hajduk more than anything else was the small white sheepskin pelt with yellow leather ribbons and embroidered flowers which he always wore over his shoulder with a chain and buckle at the neck.

In the tavern Răşcanu acted dignified. He loathed the usual chatter and gossip that would take place at the tables. In fact, he didn't like talking much at all. When he entered the tavern, the peasants would move and make room for him at their tables, but Răşcanu would already have his sights set on a corner, and usually one near the musicians. As soon as he sat down, the Romani fiddler would sidle over to him, lean in, and play something just for him. The other Rom, with a cobză, would stand at the side strumming along with his goose feather. Răşcanu loved it when they played just for him, especially when they played romances that told of love and beloveds. He also loved when the musicians sang while they played. At his request, the fiddler would bend closer and sing to him, with eyes closed . . .

I loved a pair of deep blue eyes,

I love them even to this day,

But yesterday I met a pair

Even lovelier than they.

A while later the cobzăr joined him, bursting hoarsely into song.

While you eyes from yesterday,

Are nothing like that pair of blues,

It’s good to be with you a while;

But not forever, me and you.

When Răşcanu had his fill of songs, he’d wave his hand by his ear, and the musicians would slink back to their places.

***

Though Răşcanu kept aloof and had an air of self-importance, he was still a good-natured, generous man. He was always willing to lend a hand. If someone needed a wagon of heavy bags unloaded, he was ready to offer his brawny shoulders.

But when Răşcanu got drunk, he was a menace. He’d become a completely different person. By his third glass of brandy, he’d completely lose his wits. His jaw would clench shut, and his beady eyes would flicker like flaming spears. When that happened, it was dangerous to quibble with him. The merest word could set him off, provoking the greatest of rages. And whenever Răşcanu drunkenly threw himself into a fight, peasants would fall like sheaves and lie there with shattered ribs, missing teeth, and not without occasion, cracked skulls.

After a fight like that, Răşcanu would come back to the tavern riddled with guilt and regret. My father would lecture him and he, Răşcanu, would listen to my father’s scolding with downcast eyes. He would swear, crossing his heart, that he was a good man, that he didn’t mean anyone any harm, and that if it wasn’t for the brandy, he never would have laid a finger on anyone. He would request that the next time he came in my father should serve him no more than two glasses of brandy. But when Sunday came around and Răşcanu finished his two glasses he’d forget all about his promise and demand more. My father would argue with him, reminding him of his oath, of his crossing his heart, but it never helped. Răşcanu would clench his jaw, shoot fire from his spearlike little eyes, and my father would have no choice. Răşcanu would get drunk again, pick another fight, and wreak his terrible wrath.

Once, when Răşcanu was drunk and fighting, he nearly killed a man. For a while the man teetered between life and death. Word of the incident reached the prefect, and there was talk that if the man died, Răşcanu would be sentenced to life in prison. Fortunately, the man recovered and Răşcanu got off with a slap on the wrist. After the incident, Răşcanu came to the tavern together with two peasants and the village priest. He looked them in the eyes and swore, crossed his heart, that he would never drink more than two glasses of brandy again. He knelt before the priest, kissed his cross, and implored the two peasants he had brought along that if he didn't keep his word, they should break his bones and throw him out of the tavern.

For a time Răşcanu kept his word. When he came into the tavern and finished his second glass of brandy, he would say to my father, “Enough!,” then slink over to a corner and not come back up to the bar for the rest of the day. The peasants celebrated Răşcanu’s becoming a gentleman.

***

A while later, Răşcanu came running into the tavern with news that his wife had borne him a child, his first child. He was overjoyed, and he ordered brandy for everyone. When he finished his second glass, he came to my father with the request that he, my father, should make an exception and allow him another glass of brandy. My father called over the two peasants, the witnesses, and consulted with them. The peasants thought long and hard and came to the conclusion that since Răşcanu had kept his word for quite some time, and since it was a special occasion, they could allow him another glass of brandy just this once.

But after Răşcanu drank his third glass, he wasn’t the same Răşcanu anymore. Everything about him changed: his eyes, his face, even his voice. He staggered around the tavern, tripping over his own feet, stumbling into one person after another. After that it was the same old story. He dragged himself over to the bar and demanded more brandy from my father. My father argued with him yet again. He reminded him of the oath that he had given the priest and the two peasants, of how he had kissed the priest’s cross, and of the man that he had nearly killed. But Răşcanu denied every single word of it.

“Not true!” he said.

“I never gave any oath! I never kissed any cross!”

My father called over the two witnesses again and demanded that they exercise their right. The two peasants looked over, and when they saw Răşcanu’s clenched jaw and the fire blazing in his eyes, they went speechless. They started stuttering, shrugging their shoulders, scratching their heads, and in the end they backed out and left the whole matter to my father.

My father stood firm: he would serve no brandy. Răşcanu was enraged.

“Brandy!” he shouted.

My father wouldn’t give in.

“Brandy!” Răşcanu struck the table. “I want brandy!”

The two witnesses ran over and pleaded with him.

“Răşcanu, you shouldn’t.”

“Răşcanu, you mustn’t.”

Răşcanu only became more enraged. He grabbed my father by the shoulders and shook him. “Brandy, Jew!”

My father wouldn’t give in. Răşcanu gnashed his teeth and slapped my father. The whole tavern went silent—dead silent. It was the first time a peasant had ever struck my father. The drunken villagers went sober from pure astonishment. They stayed seated at their tables, averting their gaze.

My father stood behind the bar, white as a sheet. He looked at the jug of wine that Răşcanu had, in his wild tantrum, knocked over and spilled onto the bar. Răşcanu stood across from him, his head burrowed into his chest. The slap had sobered him as well. He chewed on his mustache, his jaw twitching. He didn't know what to do. My father came out from behind the bar and stood in the middle of the tavern.

“Gospodari! Gentlemen!” my father said to the peasants. “For thirty years I have run this tavern, and until today no one has ever laid a hand on me. The hand that struck me today will fall off!”

My father’s final words struck fear into the crowd. They all sat frozen, their mouths agape. All over the tavern peasants began crossing themselves.

Răşcanu slunk into a corner to escape the crowd, but everyone’s eyes found him, glaring with contempt. Eventually someone took him by the arm and led him out from the tavern.

***

Răşcanu didn’t come to the tavern anymore. Even the other peasants were ashamed to show their faces for a few days. If they needed something, they sent the children.

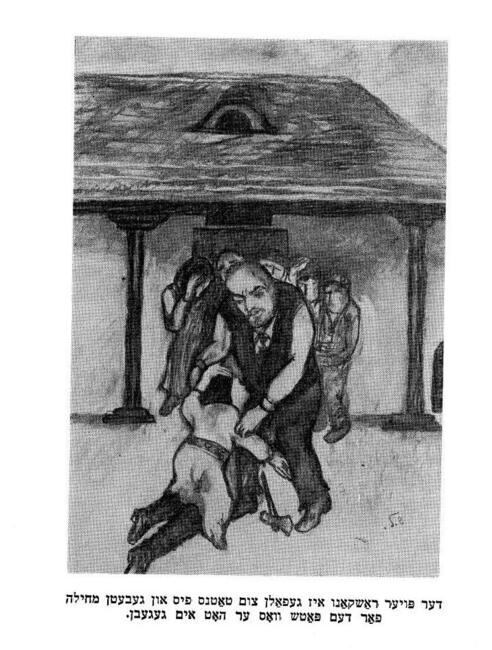

One afternoon when only a few peasants were sitting in the tavern, we suddenly heard a howl from outside. Everyone rushed out. A peasant came running out of the woods before the tavern screaming like a mad man. As he came closer, we realized that it was Răşcanu. One of his hands was covered with blood and in the other he was holding a severed finger. He ran straight to the tavern and threw himself at my father’s feet.

“Look!” he stammered pitifully, and showed him the severed finger. “Went out to the forest . . . chopping wood . . . look!” The few peasants who were standing nearby looked at Răşcanu's severed finger with terror and crossed themselves. Răşcanu clung to my father’s leg with his bloodied hand and pleaded, “Forgive me . . . I’m begging you . . . please forgive me . . .”

My father, clearly unnerved, responded, “I forgive you.”

Răşcanu kissed my father’s feet and ran home happily, his severed finger in hand.

The whole village couldn’t stop talking about my father's curse, and how it had come true. They talked about it in their huts and over their fences, in the woods and in the fields while they worked. From our village the remarkable incident traveled the dirt roads through all the neighboring villages and even reached the city.

Everywhere peasants told and retold with every detail the story of how Răşcanu struck my father, how my father cursed him, how Răşcanu went to the forest to chop wood, and how he severed a finger from the very hand that struck my father.

The priest even gave a sermon on it in church.

Ollie Elkus was a 2020 Yiddish Book Center Translation Fellow and is currently in the process of publishing his first full length translation, My Father’s Tavern, with Naydus Press. Most recently he has contributed to such notable projects as the translation of the Augustow Yizkor Book and the Ringelblum Archive’s documents of the Warsaw Ghetto. He is a Yiddish translator of printed prose and poetry as well as handwritten letters and postcards, but he also likes to bake bread, play drums, and drink tea. He can be reached through his website ohelkustranslations.com or by emailing him directly at [email protected].