Destined to Create

Speech by Rokhl Korn, translated by Michael Yashinsky

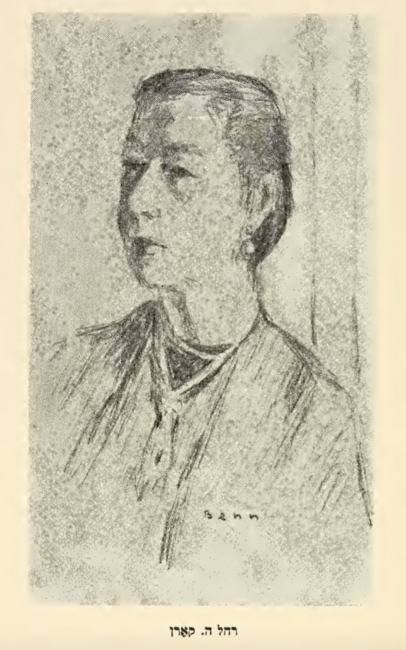

In her latter years, long after attaining fame and admiration as a “poet of the Jewish people,” Rokhl Korn marked the publication of her book Farbitene vor (A Changing Reality) at Montreal’s Jewish Public Library in November 1977 by speaking about youth and creative birth. What produced the poetic impulse in her as a child, and what gives rise to a poet in any era? Here she hazards an answer, with her decades of struggle evident in her worn but powerful voice, which her fellow Montreal Yiddish poet Chava Rosenfarb described as “hoarse, cello-like, and deep from too much smoking.” To me she sounds like an aged blues singer, who ambles up to the microphone not to praise herself for years of accomplishment, but to conjure up the uncertain and unknown of life once upon a time.

—Mikhl Yashinsky

I.

First of all, a good week to all of you. Whenever I get the opportunity to speak at a literary evening in Montreal, I remember the people who once were here. The people who stuck out their necks for me so that I and my little family could find a home here. I wish to acknowledge the two wonderful figures, Ida Maze and Melech Magid, may they rest in peace. They expended every last effort to settle us in Montreal and make it a home for us. We treasure the friendship that they demonstrated every step of the way.

For this evening’s event, which was planned with so much heart and so much respect, I must thank, first of all, the administration of the Jewish Public Library and all of the Jewish cultural institutions that have contributed.

You must have realized that the chairman of the event has now become my rival. He spoke like a poet tonight, did Artur Lermer, truly! Outstanding. Sharp, concise, to the point—and so eloquent. And as for [Yankev] Zipper, I don’t know what to say. He’s already snatched away the poems that I myself had planned to recite! Because his lecture was itself a poem. I thank both of them with my whole heart.

II.

I often reflect on, and try to puzzle out, what led me to become a writer of the Jewish people. I then conclude that it was destiny which led me to it—because I am one of the few writers, and maybe the only one, that had no escort conducting them to the canopy for their marriage with Yiddish literature.

Most Yiddish writers were born and raised in cities or towns where there were—even before World War I—writers’ associations, clubs, libraries, and especially a Yiddish newspaper that everyone read. In its pages were printed sketches, articles, poems, and short stories from the celebrated Yiddish writers of the day. And from time to time, a living writer would drop in and give a lecture.

Everyone knows, for example, about Yitskhok Leyb Peretz’s house in Warsaw, frequently visited by authors. He acted as a father to them. How many Yiddish writers would indeed never have become Yiddish writers if not for the help and encouragement of Yitskhok Leyb Peretz!

But I was born and raised on a farm, ringed with fields and forests, where even to arrive at the nearest village was a serious journey, especially for a child’s tiny feet.

I had no friends. Instead of friends, I had trees, and I spoke to them. And as regards Yiddish literature, Yiddish literary unions! Here’s what I knew: my father would sometimes study the holy books, and sometimes chatted about the Rambam. My mother kept a few German books on her shelf and some illustrated monthlies. But how would women occupy themselves in the evenings? They plucked down from goose feathers or shelled beans and peas.

So, as you can see, I had no books to read. I myself do not know what pushed me towards literature . . .

Excerpt that in wintertime, I would sit on the daybed in the kitchen and look through the window on the snow-covered expanse, and especially at the orchard, with its small, young sour cherry trees, their crowns just barely peeking out over the fallen snow which had formed a fortress around our house. And I would read a dark calligraphy etched into the white snow, the tracks of wild animals that had emerged from the forest to pay us visits in the night: foxes, hares, does, and sometimes even a wild boar.

This was the writing that I read.

The first real volume that ever fell into my hands was a torn little paperback belonging to my cousin Ester Likht, who was three years older than I. She had come from Sambor to spend her holiday with us. It would seem that the paperback meant nothing to her, seeing as she left it behind.

But to this very day I cannot forget it. In it was a story about a glass mountain, another about a wildman of the woods, and a third about a young prince that was missing not only its beginning but also its middle, and furthermore its end.

I was so enchanted that I took the story as a model. I decided that I must become like the sorceress who had bewitched the prince, but instead unwitch him from his everlasting sleep with a kiss in the form of . . . a word.

III.

Tonight I will also attempt to puzzle out what, in essence, is poetry. To me it seems that it is a magical transporter through time and space because it manages to contain the present, the past, even the future. Poetry is also the only literary medium that allows for the deformation of reality in service of artistic vision while at the same time endowing that vision with a marked purpose defined by all the attributes of reality.

In poetic creation, a formidable place is occupied by the word. Just like a person, every word has its fortune, its destiny. And though the poet may unite certain words in an indestructible bond, it is clear that they themselves had already been fixed to each other since ages ago.

Often the poet will take faded words, lying forgotten and cobwebbed. He shakes off their dust, collected over generations, and marries them off to new images. He conducts them to a new breyshis, a second genesis.

He also sets words as witnesses to the eternal struggle between justice and injustice, between purity and impurity.

At the same time, the poet is the executor of an estate, who comes to collect the debts that the people owes to itself . He has no inherited pedigree, no landed rights, no epaulets affixed to him through a formal nomination from the royal authority of literature and art.

Here, the inheritance left by a father or a grandfather counts for nothing. Here, the only thing that decides his rank is the living word of the writer himself. But a great poet or artist is no coincidence in the history of a people. He is the logical consequence of historical developments, a product of ceaseless labor that has lasted generations.

Centuries are spent toiling in the dark laboratory of the national subconscious in order to produce such a perfect individual who could become the people’s memory, its tongue, and—its conscience.

His rise may not be attributed only to himself but rather, should be considered an answer to the nation’s concealed questioning of its own fears, of its own dreams. Only then, when the people itself is creative, when it searches and struggles, when it collects its debts from itself alone, the answer comes—in the form of a tremendous poetic talent.

The sphere of literature and art, in my opinion, is dominated by a mystical command of all births, which operates to produce a perfect individual. But this nature must also rest from her intense activity because even in this domain there reigns that old, inspired Jewish law: shmite, the sabbatical year of fallowness. One must be patient. One must wait. But in the meantime, the people itself must supply the intellectual raw material through its own reserves of creative power.

I.

קודם־כּל, אַ גוטע װאָך אײַך אַלע. שטענדיק, װען עס קומט מיר אױס צו נעמען אָנטײל אין אַן אָװנט אין מאָנטרעאַל, און רעדן, דערמאַן איך זיך װער ס'איז געװעזן, װער סע האָט גורם געװען, אײַנשטעלן זיך, אַז איך זאָל מיט מײַן קלײנער משפּחה געפֿינען דאָ אַ הײם. װעל איך דערמאָנען די צװײ װוּנדערלעכע געשטאַלטן, עדה מאַזע און מלך מאַגיד, עליו־השלום, און עליה־השלום, װאָס האָבן געמאַכט אַלע אָנשטרענגונגען, כּדי מיר זאָלן זיך באַזעצן אין מאָנטרעאַל, איז געװאָרן אונדזער הײם, און מיר שאַצן אָפּ אָט די באַציִונג װאָס מע װײַזט אַרױס אױף שריט און טריט אַלע.

פֿאַר דעם הײַנטיקן אָװנט װאָס איז אַזוי, מיט אַזױ פֿיל האַרץ און באַציִונג געװאָרן אײַנגעאָרדענט, װעל איך קודם־כּל דאַנקן דער פֿאַרװאַלטונג פֿון דער ייִדישער ביבליִאָטעק און די אַלע ייִדישע קולטור־אינסטיטוציעס, װאָס האָבן זיך אָנגעשלאָסן אין דעם אָװנט.

נו, איר פֿאַרשטײט אַלײן אַז דער פֿאָרזיצער פֿון דעם אָװנט האָט פּשוט, איז געװאָרן אַ קאָנקורענט, ער האָט גערעדט װי אַ פּאָעט הײַנט, אַרטור לערמער, באמת. אױסערגעװײנטלעך. צימצומדיק און קורץ, צו דער זאַך, און אַזױ פֿײַן. און װעגן זיפּערן, װײס איך שױן אַלײן נישט װאָס צו זאָגן. ער האָט דאָך אַרױסגענומען באמת די לידער אַפֿילו װאָס איך האָב בדעה געהאַט צו רעציטירן. עס איז געװעזן אַזױ . . . זײַן רעפֿעראַט איז געװעזן אַ פּאָעמע. און איך דאַנק זײ פֿון גאַנצן האַרצן.

II.

אָפֿט טראַכט איך און פּרוּװ דערגײן װאָס אײגנטלעך האָט גורם געװען אַז איך בין געװאָרן אַ שרײַבערין בײַם ייִדישן פֿאָלק. און איך קום צו דער מסקנא אַז באַשערטקײט האָט מיך געפֿירט דערצו. װײַל איך געהער צו די געצײלטע, און אפֿשר גאָר בין איך די אײנציקע, װאָס האָט נישט געהאַט קײן שום אונטערפֿירער אונטער דער חופּה מיט דער ייִדישער ליטעראַטור.

דאָס רובֿ ייִדישע שרײַבער זענען געבױרן געװאָרן, דערצױגן, אין שטעט אָדער שטעטלעך, װוּ עס זענען, נאָך פֿאַר דער ערשטער װעלט־מלחמה, געװעזן פֿאַראײנען, קלובן, ביבליאָטעקן, און װער שמועסט, אַ ייִדישער טאָג־צײַטבלאַט, צײַטונג װאָס יעדער האָט געלײענט, װוּ עס זענען געװעזן געדרוקט סײַ סקיצן, סײַ פֿעליעטאָנען, לידער, און דערצײלונגען, פֿון די דעמאָלטיקע ייִדישע שרײַבער. און פֿון צײַט צו צײַט פֿלעגט זיך נאָך אַראָפּכאַפּן אַ לעבעדיקער שרײַבער מיט אַ רעפֿעראַט.

און אין װאַרשע למשל װײסט יעדער װעגן יצחק לײב פּרצס שטוב װוּ די שרײַבערס זענען געװעזן אײַנגײן און ער האָט זיך פֿאָטערלעך באַצױגן צו זײ. װיפֿל, אַ סך, שרײַבער װאָלטן באמת נישט געװאָרן קײן ייִדישע שרײַבער, װען נישט די הילף פֿון יצחק לײב פּרצן און זײַן דערמונטערונג!

אָבער איך בין געבױרן געװאָרן און ערצױגן אױף אַ פֿילװעריק אַרומגערינגלט מיט װעלדער און פֿעלדער, װוּ אַפֿילו צום נאָענטן דאָרף איז געװעזן אַ מהלך, בפֿרט פֿאַר קינדערישע, קלײנע פֿיס.

קײן חבֿרטעס האָב איך נישט געהאַט. אָנשטאָט חבֿרטעס האָב איך געהאַט די בײמער צו װעלכע איך האָב גערעדט. און װאָס שײך ליטעראַטור, ייִדישע ליטעראַטור־פֿאַראײנען, איך װײס, מײַן טאַטע פֿלעגט אַרײַנקוקן אין אַ ספֿר. איך דערמאַן זיך אַז מע האָט געשמועסט װעגן ראַמבאַם. מײַן מאַמע האָט געהאַט אױף אַן עטאַזשערקע אַ כּמה, עטלעכע ביכער דײַטשע, אילוסטרירטע מאָנאַטשריפֿטן. אָבער אין די אָװנטן, װאָס האָט מען געטון, פֿרױען, װאָס האָבן געטון? מע האָט געפֿליקט פֿעדערן אָדער פֿון די שױטן אױסגעשײלט אַרבעס און פֿאַסאָליעס.

איז אַזױ אַז איך האָב נישט געהאַט קײן שום בוך צום לײענען. איך װײס אַלײן נישט װאָס האָט מיך געשטױסן צו דעם, צו דער ליטעראַטור . . .

סײַדן אין די װינטערטעג פֿלעג איך זיצן אױפֿן באַנקבעטל אין קיך, קוקן דורכן פֿענצטער, אױף דעם פֿאַרשנײטן שטח און דער סאָד איבערהױפּט, די קלײנע, די יונגע װײַנשל־בײמער, קױם אַרױסגעזען די װערכעס פֿון דעם אָנגעשיטן שנײ װאָס איז געװען װי אַ פֿעסטונג אַרום דעם הױז. און איך פֿלעג לײענען אַ טונקלען כּתבֿ אױף אָט דעם װײַסן שנײ, דאָס זענען געװען די שפּורן פֿון װילדע חיות װאָס זענען פֿון װאַלד געקומען אום צו אָפּשטאַטן אין די נעכט װיזיטן. דאָס זענען געװעזן פֿוקסן, האָזן, סאַרנעס, און טײל מאָל אױך, אַ װילד־חזיר.

פֿלעג איך אָט לײענען אָט די דאָזיקע שריפֿט.

דאָס ערשטע בוך װאָס מיר איז אַרײַנגעפֿאַלן אין די הענט איז געװעזן אַ צעריסן ביכל װאָס מײַן קוזינע עסטער ליכט, עלטער פֿון מיר מיט אַ דרײַ יאָר, װאָס איז געקומען פֿון סאַמבער אױף װאַקאַציע. און װײַזט אױס אַז דאָס ביכל האָט שױן צו גאָרנישט געטױגט װײַל זי האָט עס איבערגעלאָזט.

ביז הײַנטיקן טאָג קען איך נישט פֿאַרגעסן. דאָס איז געװען אַ מעשׂה װעגן דעם גלעזערנעם באַרג, אַ מעשׂה װעגן אַ װאַלדמענטש, און נאָך אַ דריטע מעשׂה װעגן אַ יונגן פּרינץ װאָס האָט געפֿעלט סײַ דער אָנהײב סײַ דער מיטן און סײַ דער סוף.

איך בין אַזױ פֿאַרכּישופֿט געװאָרן, אַז איך בין נאָכגעגאַנגען אָט דער מעשׂה און איך האָב געטראַכט אַז איך דאַרף צוקומען צו דער מכשפֿה װאָס האָט פֿאַרכּישופֿט דעם פּרינץ, און אַנטכּישוף אים פֿון דעם דאָזיקן לאַנגען שלאָף מיט אַ קוש פֿונעם װאָרט.

III.

און אױך צו דער צײַט, הײַנט פּרוּװ איך צו דערגײן װאָס איז אײגנטלעך דיכטונג. מיר דאַכט אַז דיכטונג איז אַ קפֿיצת-הדרך דורך צײַט און רױם, װײַל זי שליסט אײַן אין זיך סײַ די קעגנװאַרט, סײַ די פֿאַרגאַנגענהײט, סײַ די צוקונפֿט. און דיכטונג איז אױך די אײנציקע ליטעראַרישע פֿאָרעם װאָס קען זיך פֿאַרגינען צו דעפֿאָרמירן די װירקלעכקײט אױפֿן חשבון פֿון װיזיע; גלײַכצײַטיק מוז זי געבן דער װיזיע אַ באַשטימונג לױט אַלע אַטריבוטן פֿון רעאַליטעט.

אַ באַזונדער אָרט פֿאַרנעמט אין דיכטערישן שאַפֿן דאָס װאָרט. פּונקט װי אַ מענטש האָט זיך יעדעס װאָרט זײַן מזל, זײַן באַשערטקײט. און אַזש דער דיכטער פֿאַראײניקט די װערטער אין אַ נישט צערײַסבאַרן בונד, גלײַך זײ, נאָר זײ, װאָלטן געװען באַשטימט פֿאַר זיך פֿון קדמונים אָן.

אָפֿט נעמט דער דיכטער װערטער אָפּגעבליאַקעװעטע, װאָס זענען געלעגן פֿאַרגעסן און פֿאַרשפּינװעבט, טרײסלט אָפּ פֿון זײ דעם דױרעסדיקן שטױב, פֿאַרזיװגט זײ מיט נײַע אימאַזשן, און פֿירט זײ צו צו אַ נײַעם בראשית.

ער שטעלט אױך װערטער װי עדות אין אײביקן קאַמף צװישן יושר און אומרעכט, צװישן קדושה און טומאה.

גלײַכצײַטיק איז דער דיכטער אַן עקזעקוטאָר װאָס קומט אײַנמאָנען די חובֿות װאָס דאָס פֿאָלק איז זיך אַלײן שולדיק. נישטאָ קײן געירשנטער ייִחוס, נישטאָ פֿאַראַן קײן רעכט פֿון פּױערשאַפֿט, נישטאָ קײן שליפֿעס אים צו טאָן [?] װאָס זאָלן קומען דורך אַ דרױסנדיקער נאָמינאַציע אין מלכות פֿון ליטעראַטור און קונסט.

דאָ גילט נישט קײן ירושה צוגעגרײטע פֿון אַ טאַטן אָדער זײדן. דאָ האָט צו באַשטימען דעם ראַנג בלױז דאָס לעבעדיקע װאָרט פֿון שרײַבער גופֿא. אַ גרױסער דיכטער אָדער קינסטלער איז נישט קײן צופֿעליקײט אין דער געשיכטע פֿון אַ פֿאָלק. ער איז אַ פּועל־יוצא פֿון אַ צװעקמעסיקער געשיכטלעכער אַנטװיקלונג, אַ פּראָדוקט פֿון דורותדיקער האָרעװאַניע.

לאַנגע דורות האָבן זיך געמיט אין דער טונקעלער לאַבאָראַטאָריע פֿון פֿאָלקס־אונטערבאַװוּסטזײַן, אױסצופּראָדוצירן אַזאַ פּערפֿעקטן יחיד װאָס זאָל װערן דעם פֿאָלקס זכּרון, צונג, און געװיסן.

דאָס איז נישט פֿאָרגעקומען אַלײן פֿון זיך, נײַערט אַלס אַן ענטפֿער צום פֿאָלקס־פֿאַרטײַעט פֿרעגן זײַנע בענקשאַפֿטן און טרױמען. נאָר דעמאָלט, װען דאָס פֿאָלק אַלײן איז שעפֿעריש, זוכט און ראַנגלט זיך, האַלט אין אײַנמאָנען בײַ זיך גופֿא, קומט דער ענטפֿער אין דער געשטאַלט פֿון אַ גרױסן טאַלאַנט.

אין דער ספֿערע פֿון ליטעראַטור און קונסט, דאָמינירט, לױט מײַן מײנונג, אַ מיסטישער געבורטן־קאָנטראָל, נאָכן אױספּראָדוצירן אַ פּערפֿעקטן יחיד, מוז זיך די נאַטור אָפּרוען פֿון איר גרױסער אָנגעשטרענגטקײט, װײַל אױך אױף דעם געביט, הערשט דאָס אַלץ ייִדישע געניאַלע געזעץ פֿון שמיטה, מוז מען האָבן געדולד און װאַרטן. אָבער אינצװישן, מוז דאָס פֿאָלק אַלײן צושטעלן די נױטיקע גײַסטיקע זאַפּאַסן דורך אײגענער שעפֿערישקײט.