Sholem Aleichem: The Quintessential Yiddish Writer

Sholem Aleichem created many of the most enduring works of modern Yiddish fiction.

Sholem Aleichem, the pseudonym of a Russified Jewish intellectual named Solomon Rabinovitz (1859–1916), created many of the most enduring works of modern Yiddish fiction.

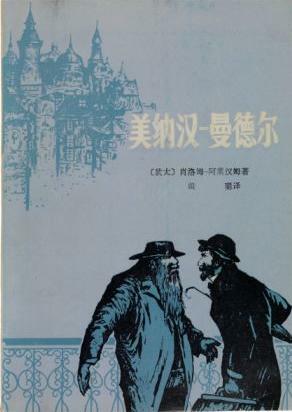

In the epistolary novel Menakhem-Mendl, a hapless luftmentsh, a man of ndeterminate profession, exchanges lofty letters about his latest hare-brained business schemes with Sheyne-Sheyndl, his sharp-tongued, down-to-earth wife.

Motl the Cantor’s Son, an irrepressible orphan, gets into mischief in the old country and the new.

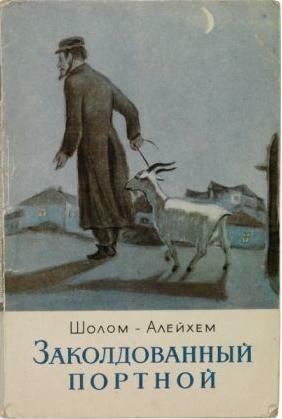

Kasrilevke is a fictional shtetl where restaurant owners argue with their customers, firemen do more talking than dousing, and even the thieves speak Yiddish. Tevye the Dairyman, the most famous of Sholem Aleichem’s characters, relies on his own devices—an imperfect knowledge of Hebrew texts and an innate Jewish sensibility—to respond to the challenges posed by each of his five headstrong daughters.

Professor Ruth Wisse praises Sholem Aleichem as the “greatest genius that Yiddish literature ever produced.” Sholem Aleichem was monumental in recasting and interpreting the Jewish people through his literature, creating an image of the Jewish people that they then internalized.

In these and other works, Sholem Aleichem’s small-town characters act out the grand themes of modern literature: the breakdown of tradition, the generation gap, gender wars, class struggle, urbanization, immigration, politics, war, revolution—and the fate of Yiddish itself. Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish prose is zaftig (juicy) and dense: his characters react to social and political upheaval with a torrent of idioms, proverbs, intentional misquotations, wordplays and malapropisms. Although these linguistic feats can only be approximated in translation, the complexity of the language implicitly critiques, ridicules and resists the outside forces threatening Jewish tradition and community. In Sholem Aleichem’s stories, Yiddish is a weapon, a means of asserting continuity between a rich past and an uncertain future.

This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the David Berg Foundation.