Sholem Asch—The First Memorial Address

— David Mazower, published on July 12, 2020.

He loved his fellowmen . . . and their fate and their emotions were the stuff of his own passion.

Yiddish Book Center bibliographer and editorial director, David Mazower, is Sholem Asch's great-grandson. Here he introduces a text he recently saw for the first time—the memorial tribute to Asch delivered by Rabbi Harold Reinhart at Westminster Synagogue on July 14, 1957.

My grandmother didn't have much time for rabbis. As Sholem Asch's daughter, she had seen firsthand how attacks in the name of Judaism had sapped her father's spirit throughout his life and especially in the 1940s and '50s. Later, in her work with Westminster Synagogue's Memorial Scrolls Trust, overseeing the fate of 1,564 Torah scrolls from destroyed communities in former Czechoslavia, she was in frequent contact with congregations around the world. It's fair to say that her view of rabbis and synagogue leaders didn't improve as a result of that experience.

There was one rabbi, however, whom my grandmother regarded with unconditional warmth and a respect bordering on reverence. His name was Harold Reinhart, and he served as spiritual leader of Westminster Synagogue from 1957 until his death in 1969. Rabbi Reinhart was the reason my grandparents were members of the shul, and the reason my grandmother devoted decades of her life as a volunteer to the Memorial Scrolls Trust.

I hadn't thought about Rabbi Reinhart in a long time. However, a few weeks ago, a friend sent me the August 1957 edition of the Synagogue Review. For the first time, I found myself reading the text of the memorial address for Sholem Asch that Rabbi Reinhart gave at the Westminster Synagogue on July 14, 1957. I imagined myself back in that elegant redbrick townhouse in Knightsbridge, where I used to visit my grandmother in her office on the top floor. She worked alongside a Hasidic scribe, whose skills in restoring damaged parchment and repairing fading lettering were equal to those of any plastic surgeon. In the storeroom, the Czech scrolls lay on wooden racks, thick parchment rolls longer than a small child, with protruding wooden or ivory handles.

As I read Rabbi Reinhart's words about my great-grandfather, images flickered in my mind, scrolling back and forth between those mute bundles of parchment and the elderly Asch. My great-grandfather had retreated almost completely into the world of the Hebrew Bible in his last years, retelling ancient stories like that of Jacob and Rachel—his last unfinished manuscript. One could argue that Asch saw his last writings as a form of modern Torah, animating the Jewish covenant with God and reimagining the foundational narratives of Jewish peoplehood.

Sholem Asch had been visiting London and staying with my grandmother when he died on July 10, 1957. On July 12 he was buried in Hoop Lane Cemetery, where his grave is marked today by a simple, low monument representing an open book. Two days later, the memorial service was held at the Westminster Synagogue. I don't know if Rabbi Reinhart ever met my great-grandfather, but his address is a remarkable document. His assignment was unenviable: to weigh up Asch's complex personality and his place in Jewish life and letters in a few hundred words. And to do so, moreover, in the presence of grieving family and friends. He pulls it off brilliantly, capturing some of the essential aspects of Asch's larger than life personality with understanding, insight, and empathy.

I understand now why my grandmother held Rabbi Reinhart in such high esteem. I also learned for the first time that my great-grandfather's funeral casket contained ash from the ruins of Treblinka, the camp where his beloved father-in-law met his death. Michael Zylberberg, who placed it there, was a close friend of Asch, a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto, and the author of an important book about his wartime experiences.

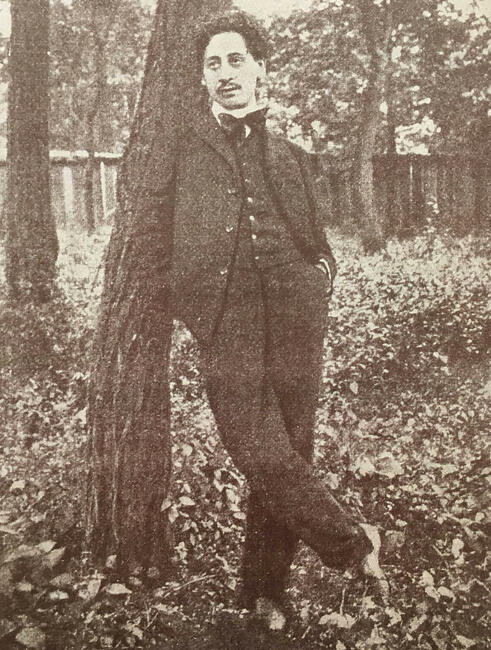

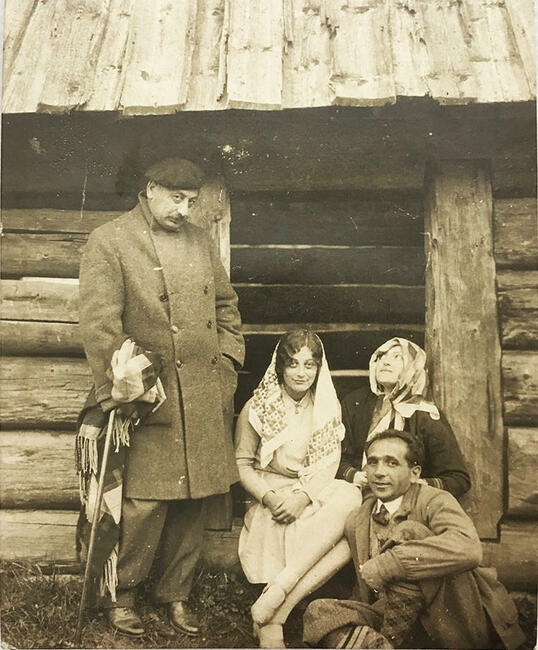

Here is the full text of Rabbi Reinhart's memorial address, followed by a selection of photos showing my great-grandfather at different stages of his life.

“We are met this afternoon not only to take our earthly farewell of a distinguished and beloved figure in Jewry, who for more than fifty years poured out his heart to millions of readers, not only to express our sympathy to his near and dear ones, who are bereft in his passing, not only to testify that we share their sorrow, but also and most of all to voice our thanksgiving to God for endowing Sholem Asch with greatness and causing him to move among us here on this earth for a time. There will be other occasions when his rare literary genius will be assessed and proclaimed. Today, in this sacred room, we would speak a few words about the essential qualities of his personality, which we will always remember.

"First, he was possessed of a depth of human understanding. He loved his fellowmen: he lived in their lives and their experiences, and their fate and their emotions were the stuff of his own passion. He was the individual he was because he lived so naturally in sympathy with his fellowmen. In this, as in other characteristics, he kept throughout his life something of the spontaneity of childhood. He was a big boy always. He was a mouthpiece of his own Polish background; and the genius of that society was focused in his soul. When just before the funeral on Friday, Michael Zylberberg performed the ceremony of depositing in the sanctified case which contained the mortal remains of Sholem Asch some dust from the ruins of Treblinka, he eloquently symbolized Sholem Asch’s representative role as the heart and voice of the old Polish Jewry. So also did his fellows evoke his sympathy in America. So, in Israel, where in these latter years he experienced real happiness in the unconditioned welcome from fellows Jews, and in the sight of courage and enterprise and hope. And so also, and not least of all, here in England where he rejoiced in freedom and where he had the comfort of loved ones.

"Secondly, we will remember him as a controversial figure. He loved his fellowman, but he served them in accordance with his own ideals. He went to his reward in the week in which we read the Portion Pinchas. He possessed something of the Pinchas passion and the zeal of an Elijah. Not that he failed to value the approval of his fellowmen. Indeed he craved commendation and praise and even adulation. But for these rewards he would not betray truth. There was a burning fire within him; and he knew that honour is more precious than life.

"And thirdly, he was a religious man. His human sympathy was from soul to soul. His service of an ideal was for the sake of Heaven. Howsoever unconventional his expression sometimes was, the fact is that he appreciated eternal values. He believed in olam haba, the life of eternity. That, essentially, is what we mean by a religious man.

"In the memorial prayer which we are about to read, we will mention his name not only as that of our brother, but also, using a term reserved for the learned and the wise, our teacher. He has blessed us with his spirit. His is the peace which comes of struggle, the peace which the prophets knew—the prophets into whose soul he penetrated and of whom he wrote so well. In their bliss he shares.”

UPDATE: Once this article was published, I sent it to my mum. That’s her in the second to last photo (“granddaughter Miriam”). She replied, “Sholem certainly knew Reinhart; he married us.” (My parents married in the West London Synagogue, where Rabbi Reinhart was officiating before he took up the post at Westminster, and Asch and his wife Madzhe, then living in London, were there). Moral: when writing about your family, always consult your mother before you publish!