Of Friends and Brothers-in-Law

A Mimi Pinzon Mystery

On a rainy October day, twenty-three boxes of books appeared unannounced at the Yiddish Book Center’s doorstep. Packed delicately, these boxes held the collection of scholar Norma Fain Pratt. With hundreds of rare books written by women in her collection, many of which I was unfamiliar with, each was a dazzling surprise, an invaluable contribution to the Center’s core collection. One author in particular caught my eye: Mimi Pinzon, the Argentinian author of Der hoyf on fentster (The Courtyard without Windows). Pratt donated two copies of this rare book not yet in our collection, one containing an inscription. Among the hundreds of new books received, I was particularly intrigued by what this fifty-seven-year-old note could reveal.

Born in Tserkov, Ukraine (modern day Bila Tserkva), in 1910, four-year-old Pinzon—then named Adela Weinstein-Shliapochnik—left her home with her parents and headed to Buenos Aires. Life in a conventillo—a building that housed several poor, multiethnic families, comparable to New York’s Lower East Side tenements—became the backdrop to her 1965 semi-autobiographical novel. Later in life, Pinzon became involved in Communist politics, leftist Yiddish schools, and translating many esteemed Spanish writers into Yiddish, including Luis Borges, Alfonsina Storni and Horacio Quiroga.

In 1926, Pinzon published her first Yiddish short story in the Argentinian Yiddish paper Di prese. She assumed her new pseudonym Mimi Pinzon, the Hispanicized name of the French seamstress and protagonist in Alfred de Musset's 1841 short story “La Grisette” and sent her work out to the papers. Though critics soon lauded Pinzon’s colorful and idiomatic language, her pseudonym created quite the commotion among Yiddish writers in Buenos Aires. Her second story, “Di legende fun baranka-belgrano,” also submitted in 1926, sat at the desk of Di prese’s editor for a whole year. He was in disbelief that a Jewish kid raised in a Spanish-speaking home, at only age sixteen, could write so brilliantly in Yiddish. It took several interrogations before he finally believed Pinzon was the author and agreed to publish her once more.

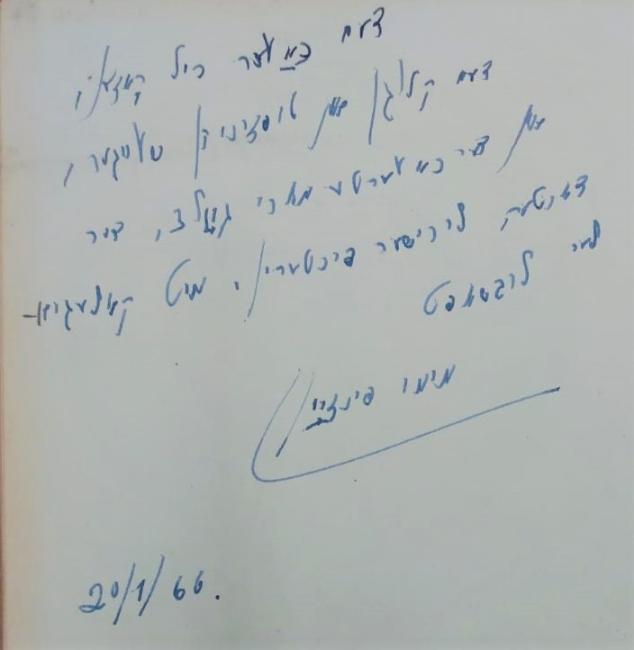

The inscription on the front page of the book that had just entered our collection reads:

To my friend Khil Rozen,

My smart and profound brother-in-law,

And my friend Mari Gold, the gentle and lyrical poet,

with collegial love.

Mimi Pinzon 20-1-66

דעם כאַװער כיל ראָזען,

דעם קלוגן און טיפֿזיניקן שװאָגער,

און דער כאַװערטע מאַרי גאָלד, דער צאַרטער, לירישער דיכטערין,

מיט קאָלעגיאַלער ליבשאַפֿט.

מימי פּינזאָן 20-1-66

This note seemed perfectly normal to me at first glance. Pinzon was sending her warm regards to her brother-in-law and his wife, both of them also Argentinian writers. However, none of the sources I had read about Pinzon mentioned siblings, and I struggled to track down her husband’s family tree, so my curiosity continued to grow.

I reached out to Jonah Lubin, one of the Yiddish Book Center’s 2022–2023 translation fellows, who is translating Pinzon’s novel. I was curious if he could point me to more information or primary sources about Pinzon’s life. Unfortunately, there are very few. He did, however, give me a glimpse into her work in translation, explaining how polyglossic, disjointed, difficult, literary, and riddled-with-em-dashes this undertaking is. Here’s a taste of what he means:

The courtyard had never before been so cheerful. Not even when Angiulin stabbed his wife Alfonsina. But however cheerful it may have been out there, Etl's parents were no happier at home. Etl would burst through the door in the evenings, run off her feet in three languages—Yiddish, Spanish, and Italian— she'd burst in and want to tell them everything all at once and it was like she was plunged into cold water—… Etl thought: her parents were so weird: out in the courtyard was pandemonium, people talking, complaining, fighting – it was cheerful as could be and they— they were sitting at home, completely disinterested.

—translated by Jonah Lubin

Der hoyf on fentster tells the story of a young Jewish girl named Etl, a recent immigrant to Buenos Aires. Through Etl, one of the first girls to be featured as the protagonist in a Yiddish novel, Pinzon offers her vision of nationhood in Argentina through the synecdoche of the hoyf (courtyard) where the community of Spanish-, Italian-, and Yiddish-speaking immigrants congregate in the conventillo. By writing this novel in Yiddish, Pinzon pushed back against the pressure of state monolingualism in Argentina, demonstrating her commitment to cultural and ethnic pluralism.

Captivated by Pinzon’s prose and the story of her start as a writer, I wanted to understand the inscription as best I could in order to paint a picture of a relatively unknown author. Was Yekhiel Rozen actually her brother-in-law or did she mean this symbolically? Did Pinzon have a sister, perhaps that Yekhiel Rozen was once married to? Could Mari Gold be Pinzon's sister? What about her husband’s family? How did this book end up in Los Angeles in the home of Norma Fain Pratt nearly sixty years later?

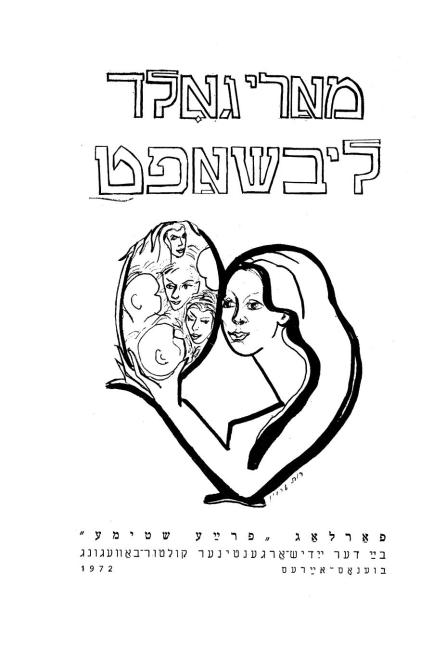

After searching the Yiddish Book Center’s digital collection, I could confirm that Mari Gold was married to Yekhiel Rozen. And in doing so, I found that Pinzon wrote an impassioned introduction to Mari Gold's 1972 collection of poems Libshaft, where she contemplates how Gold’s poetry opens up the intimate world of a woman.

In the foreword, Pinzon writes:

Strange, tangled, and secretive – incomprehensible are the ways of Yiddish literature. Sometimes—propelled upwards from invisible, unsuspected, underground forces. Sometimes—concealed, with dense interlacing branches, casting a shadow. Who can know—which underground nectars they are intoxicated with? – Through which roads, detours, and paths,—have they forged a path to the illustrious light—?...

I might never know why Pinzon referred to Yekhiel Rozen as her brother-in-law. What I have learned instead, is what a fierce supporter of Yiddish particularity and women’s writing in Yiddish Pinzon was. She believed so strongly in Mari Gold’s writing, I was led to believe they must be related somehow. Whether or not that is true, it is evident that the two are close friends, sharing success and joy from each other’s literary endeavors in Yiddish. If not for this note, I would never have learned of the two writers’ deep comradery.

It is evident that the two are close friends, sharing success and joy from each other’s literary endeavors in Yiddish.

Concerning the recovery of Yiddish novels written by women, Anita Norich is quoted in a 2022 New York Times article, “How Yiddish Scholars Are Rescuing Women’s Novels From Obscurity,” that the process of uncovering women’s writing made her feel “like a combination of sleuth, explorer, archaeologist and obsessive.” I now know what she means.

May 2023

Charlotte Apter—Richard S. Herman Fellow and a native of West Hartford, CT.—is a graduate of Oberlin College where she studied history, religion, and Jewish studies. In high school, Charlotte was a student at the Great Jewish Books Summer Program and in college she completed both tracks of the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program. At Oberlin, she wrote a senior thesis chronicling the political work of Clara Lemlich and Rose Schneiderman, two prominent Jewish labor organizers in the years following the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. She is delighted to be a part of the bibliography team this year.