A Focus On: Itzik Manger

Itzik Manger was born in Czernowitz in 1901 and made his literary reputation in Warsaw, where he lived from 1928 to 1938. Manger's poetry was heavily influenced by German romantic poetry and new, modernist styles of writing. He wrote sophisticated verse and experimented with rhythmic and metrical patterns before embracing the ballad as his signature mode. Manger also wrote extraordinary essays, stories, plays, and portions of a fictional autobiography.

Some of the richest sources of information about Manger's life and work are the memorial evenings held across the Yiddish world after his death in 1969. Our Frances Brandt Online Yiddish Audio Library contains the full programs of two such evenings, one recorded in Montreal immediately after Manger's death, another recorded several months later in Tel Aviv. Speakers at the memorial programs highlight the signature features of Manger's artistic style—his poetics of wandering, musicality, and the embrace of folk imagery—while also helping us understand why Manger was so beloved.

“For Years I Wallowed” was one of Manger’s most indelible poems, and its recitation is a prominent feature of the two memorial evenings. Despite his erudition, Manger often presented himself as a vagabond. He was the wandering poet whose songs channeled the spirit of the Jewish people. "For Years I Wallowed" is the ultimate poem by the ultimate Jewish wanderer. Written in 1958, on the verge of Manger's immigration to Israel, it counterposes wanderlust and homecoming, myth and reality, the past and the now. In the poem, Manger evokes “that great poet,” Yehuda HaLevi, the legendary medieval Jewish writer whose pilgrimage poems cross over that invisible line that separates the secular from the sacred. HaLevi presented Israel as a sacred land. Manger challenges him with a different vision of the sacred: not the land of Israel, but the people Israel, holy wherever their wanderings take them. "I am your dust," Manger repeats as a refrain.

Different readers emphasize the varied musical aspects and thematic undertones of the poem. In the first recitation, recorded in Montreal immediately after Manger's death, Israel Gonshor emphasizes the autobiographical voice of the poem, stressing the poetic "I." In the second recording, the vagabond's weariness interlaces with defiance. A bilingual version of the poem, which first appeared in Pakn Treger 39, is reproduced below.

FOR YEARS I WALLOWED - Translated by Leonard Wolf

For years I wallowed about in the world,

Now I'm going home to wallow there.

With a pair of shoes and the shirt on my back,

And the stick in my hand that goes with me everywhere.

I'll not kiss your dust as that great poet did,

Though my heart, like his, is filled with song and grief

How can I kiss your dust? I am your dust.

And how, I ask you, can I kiss myself?

Still dressed in my shabby clothes

I'll stand and gape at the blue Kinneret

Like a roving prince who has found his blue

Though blue was in his dream when he first started.

I'll not kiss your blue, I'll merely stand

Silent as a shimenesre prayer myself.

How can I kiss your blue? I am your blue.

And how, I ask you, can I kiss myself?

Musing, I'll stand before your great desert,

And hear the camels' ancient tread as they

Sway with trade and Torah on their humps.

I'll hear the age-old hovering wander-song

That trembles over glowing sand and dies,

And then recalls itself and does not disappear.

I'll not kiss your sand. No, and ten times no.

How can I kiss your sand? I am your sand.

And how, I ask you, can I kiss myself?

כ' האָב זיך יאָרן געװאַלגערט אין דער פֿרעמד

כ' האָב זיך יאָרן געװאַלגערט אין דער פֿרעמד,

איצט פֿאָר איך זיך װאַלגערן אין דער הײם.

מיט אײן פּאָר שיך, אײן העמד אױפֿן לײַב ,

אין דער האַנט דעם שטעקן. װי קען איך זײַן אָן דעם?

כ'װעל נישט קושן דײַן שטױב װי יענער גרױסער פּאָעט,

כאָטש מײַן האַרץ איז אױך פֿול מיט געזאַנג און געװײן.

װאָס הײסט קושן דײַן שטױב? איך בין דײַן שטױב.

און װער קושט עס, איך בעט אײַך, זיך אַלײן?

כ'װעל שטײן פֿאַרגאַפֿט פֿאַר דעם כּנרת־בלאָ,

אין מײַנע בגדי־דלות אָנגעטאָן,

אַ פֿאַרװאָגלטער פּרינץ, װאָס האָט געפֿונען זײַן בלאָ,

און בלאָ איז זײַן חלום פֿון תּמיד אָן.

כ'װעל נישט קושן דײַן בלאָ, נאָר סתּם אַזױ

װי אַ שטילע שמונה־עשׂרה װעל איך שטײן –

װאָס הײסט קושן דײַן בלאָ? איך בין דײַן בלאָ,

און װער קושט עס, איך בעט אײַך, זיך אַלײן?

כ'װעל שטײן פֿאַרטראַכט פֿאַר דײַן מדבר גרױס

און הערן די דורות־אַלטע קעמל–טריט,

װאָס װיגן אױף זײערע הױקערס איבערן זאַמד

תּורה און סחורה, און דאָס אַלטע װאַנדערליד,

װאָס ציטערט איבער די זאַמדן הײס־צעגליט,

שטאַרבט אָפּ, דערמאָנט זיך און װיל קײנ מאָל נישט פֿאַרגײן.

כ'װעל נישט קושן דײַן זאַמד, נײן און צענ מאָל נײן.

װאָס הײסט קושן דײַן זאַמד? איך בין דײַן זאַמד,

און װער קושט עס, איך בעט אײַך, זיך אַלײן?

A Poet of Musicality and the Folk

In his eulogy, delivered at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal Z. Volkovitsh evoked two powerful symbols of Yiddish folk poetry to describe the monumentality of the loss. "The wellspring of Manger’s poetry has been muted," he said. "The emblems of his literary creation, the symbols of Yiddish folksong—the golden peacock, the pure-white goat—have been orphaned."

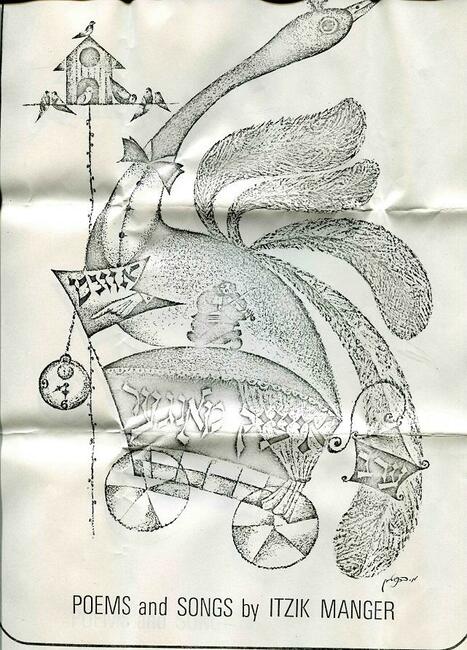

Such symbols were similarly used to promote the evening in Tel Aviv. The program cover runs wild with folk iconography. The artist depicts a peacock (in bowtie—an emblem of folklore made sophisticated), a birdhouse (perhaps to recall the many birds that populate Manger's poems), and a klezmer musician riding atop a wagon. The wagon and fiddler simultaneously recall the wandering minstrels after whom Manger fashioned himself, and the title song to the film Yidl mitn fidl, for which Manger wrote the lyrics. The song opens, "Iber felder, vegn / in a vogn hey / mit zun un vint un regn / es forn klezmer tsvey" ("Over roads and grassy planes / in a wagon filled with hay / through wind and sun and rain / two musicians make their way"). But now the wagon carries only one musician. Manger's youthful, vivacious yidl mitn fidl (Jewish boy with a violin) has been transformed into yet another Jewish folk symbol and emblem of the lost shtetl: the fiddler on the roof.

Music is an important part of Manger's creativity. In March 2013, Aaron Lansky spoke with Manger’s biographer, Efrat Gal-Ed, about Manger’s life and poetry. Here she explains his poetic appeal.

“He was not so simple," Gal-Ed said. "He was not a folk bard. He created highly sophisticated, modern Yiddish poems, which he made sound as if they were folk songs, which, I suppose, helped his popularity … The poets admired him because ... he is really able to do that which makes poetry great, and it is this merging of music and sense. Manger’s poetry is very musical.” (Listen to the full interview here.)

Manger himself connected his poetry with the music he heard in Romania. In their introduction to The World According to Itsik, David Roskies and Leonard Wolf write, “Manger described an epiphany that had occurred, aptly enough, in a tavern late one night, his muse appearing as a drunken old man, the last of a generation of beer hall singers." Manger's colorful description of the scene follows.

I was sitting one night in a tavern in Bucharest. A guest from Berlin was with me—Dr. Israel Rubin. Long past midnight an old man of some seventy years dropped in. He was well and truly drunk. This man was old Ludvig, the last of the Brody Singers.

We invited him to our table. He poured himself a large glass of wine, made a sort of Yiddishized kiddush, then later he began to sing [songs] from his Brody repertoire. …

My eyes lighted up: This! This was it! The shapes of the Brody Singers glowed in my mind. All the wedding jesters, rhymesters, and Purim players that had amused generations of Jews came alive. I will become one of them; one of “our brothers.” Perhaps what they created and sang was primitive, and not lofty poetry; but they themselves were poetry.

I remembered the lovely folksongs I had heard in my father’s workshop. What an orgy of color and sound. What a heritage lay there abandoned. Gold being trodden underfoot. And I paid attention and gazed.

(Yiddish from “Mayn veg in der yidisher literatur” (1961), reprinted in Manger, Shriftn in proze, 364-365; translation by Leonard Wolf from The World According to Itzik, xvi-xvii.)

אײן מאָל בין איך געזעסן שפּעט בײַ נאַכט אין אַ בוקאַרעשטער קרעטשמע. מיט מיר איז געזעסן אַ גאַסט פֿון בערלין ־ ד''ר ישׂראל רובין. שפּעט נאָך מיטנאַכט איז אַרײַנגעפֿאַלן אַן אַלטער מאַן פֿון אַרום זיבעציק. ער איז געװען גוט בגילופֿין. דאָס איז געװען דער לעצטער "בראָדער זינגער," דער אַלטער לודװיג.

מיר האָבן אים פֿאַרבעטן צו אונדזער טיש. ער האָט זיך אָנגעגאָסן אַ גרױס גלאָז װײַן, געמאַכט אַ מין פֿאַרייִדישטן קידוש און שפּעטער האָט ער אָנגעהױבן זינגען פֿון זײַן בראָדער רעפּערטואַר...

ס'איז מיר ליכטיק געװאָרן אין די אױגן: אָט דאָס איז דאָס! די געשטאַלטן פֿון די בראָדער זינגערס האָבן אױפֿגעליכטיקט אין מײַן דמיון. אַלע בדחנים, גראַמען־מאַכערס און פּורים־שפּילערס, װאָס האָבן אַמוזירט דורות ייִדן, זענען געװאָרן לעבעדיק. איך װעל װערן אײנער פֿון זײ, אײנער פֿון "אונדזערע ברידער." מעגלעך אַז דאָס, װאָס זײ האָבן געשאַפֿן און געזונגען, איז געװען פּרימיטיװ, גאָר נישט קײן געהױבענע פּאָעזיע, אָבער זײ אַלײן זענען דאָך געװען פּאָעזיע.

איך האָב זיך דערמאָנט די שײנע פֿאָלקסלידער װאָס איך האָב געהערט אין מײַן טאַטנס װאַרשטאַט. ס'אַראַ אָרגיע פֿון פֿאַרב און קלאַנג. אַ ירושה װאָס איז געלעגן פֿאַרװאָרלאָזט, גאָלד װאָס האָט זיך געװאַלגערט הפֿקר אונטער די פֿיס. און איך האָב דערהערט און דערזען

In an interview with Avrom Tabatchnik, Manger again described his theory of poetry. Against the soundscape of New York—a car honks, a basketball bounces—Tabatchnik and Manger discussed Manger’s sense of the musicality of poetry. Yet Manger’s answer reveals itself to be as cryptic as it is illuminating.

It’s hard to define [musicality]. But, first of all, when I say music, I mean internal music and external music. In the end, the musical [element] manifests itself through sound, as much as the word exhales the element of sound. There is also an external element, of course. Of course, the control, the stimulation is the internal music.

ס'איז אַ ביסל שװער צו דעפֿינירן די דאָזיקע זאַך. אָבער קודם-כּל, װען איך זאָג, אַז מוזיק, מײן איך די אינערלעכע און די דרױסנדיקע. סוף-כּל-סוף דאָס מוזיקאַליש מאַניפֿעסטירט זיך דורכן קלאַנג, אױף װיפֿל דאָס װאָרט אָטעמט זיך די עלעמענט פֿון קלאַנג. ס'איז דאָ בײדע איז דאָך אַ דרױסנדיקע. פֿאַרשטײט זיך אַז דער קאָנטראָל, די סטימולאַציע איז די אינערלעכסטע מוזיק. צװישן אינערלעכער מוזיק און דער דרױסנדיקער, דאַרף זײַן אַ האַרמאָניע. אין דעם זין, פֿאַרשטײ איך די מוזיקאַלישקײט פֿון דער פּאָעזיע.

Whatever Manger meant by these cryptic words, the sheer number of musical settings and arrangements of Manger's poetry points to its inherent song-like qualities. With Manger, we remember that Yiddish makes no distiction between the two forms: the word lid means both poem and song.

Reimaginings

Today Manger is perhaps best known for his reimaginings of biblical stories. Manger’s Khumesh lider (Bible Songs) was included on our list of the 100 greatest works of modern Jewish literature. At the time, Jeremy Dauber wrote, “In the ballads and poems which make up the cycle Khumesh lider, Manger fleshes out biblical characters who rarely speak in the original text. He gives them voices of their own and adds characters, ideas, and motifs which do the miraculous: they bring the great epic of the Jewish people into human perspective."

In his introduction to The World According to Itzik, David Roskies contextualized the strategy and intellectual approach behind Manger's most famous revision, Megile lider, an adaptation of the Book of Esther.

“Manger has modernized and complicated the narrative by weaving into it a romantic subplot that predates Esther’s life as Ahasuerus’s queen. In Manger’s tale, Esther’s lover is Fastrigosso, a journeyman tailor with whom Esther is planning to elope—to Vienna! Fastrigosso (his mock-Aramaic name means “a basting stitcher”) is a schlemiel antihero worthy of Sholem Aleichem. At once hapless and loveable, Fastrigosso is a member in good standing of the radical tailors’ union. When Esther becomes the queen, thus shattering his dream of marriage to her, he goes berserk and tries to assassinate the king. Possessing nothing but a penknife, the desperate young lover is comically foiled. … Whatever happened to the victorious Jews, to the timeless parable of Jewish salvation?"

In this excerpt from our Wexler Oral History Project, Motl Didner, associate director of the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene, offers another take on the Megile lider. Like Roskies, Didner explores the political thrust of Manger’s writing, here explaining it within the specific context of pre-World War II anti-Semitism. He further expounds on the symmetries between Manger and his main character.

Musical adaptations of Megile lider were incredibly popular, a regular feature of the secular Yiddish celebration of Purim. A wonderful performance of Megile lider, staged in Israel, is available as part of our collection of archival recordings. No knowledge of Yiddish is necessary to enjoy the singers' lively renditions of Manger's words.

More

The Center's collections contain many editions of Manger's books as well as an audio book of his poems and ballads. Two highlights that readers may enjoy are these reminiscences of Manger's wastrel tendencies from the Wexler Oral History Project, the first shared by Yiddish scholar Benjamin Harshav, the other shared by Norman Feinberg.