Vilner gedenken: Avrom Sutzkever in Focus

Avrom Sutzkever, 1913-2010, (Abraham Sutzkever) was the definitive Yiddish poet of the post-War period. His biography embodied the transformations of Jewish life in the twentieth century, both its catastrophes and its triumphs. “Sutzkever began writing poetry in Vilna in the 1930s,” wrote the preeminent Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse. “[He] emerged as a figurehead of cultural resistance during the Vilna Ghetto, and came to Eretz Israel in 1947, on the eve of the creation of the state.”

Wisse’s concise description of Sutzkever’s career cannot hope to capture the monumentality of his life. Sutzkever was a Partisan in the forests outside Vilna. He was showered with a hero’s welcome when he arrived—by airlift—in the Soviet Union. He helped to create and sustain Yiddish culture In Israel. He formed the literary group yung yisroel (Young Israel), and he founded the literary journal Di goldene keyt (The Golden Chain), which he edited for decades. Di goldene keyt was the premier Yiddish journal throughout its run, and Sutzkever, as editor, cultivated a generation of burgeoning writers. In the 1970s, Sutzkever began to write his Lider fun togbukh (Poems from a Diary), which further blurred the lines between the private person and the public figure. The poems from his diary allow us into his innermost spaces. His memories of friends long gone, rendered in his perfect words, became occasions of national mourning.

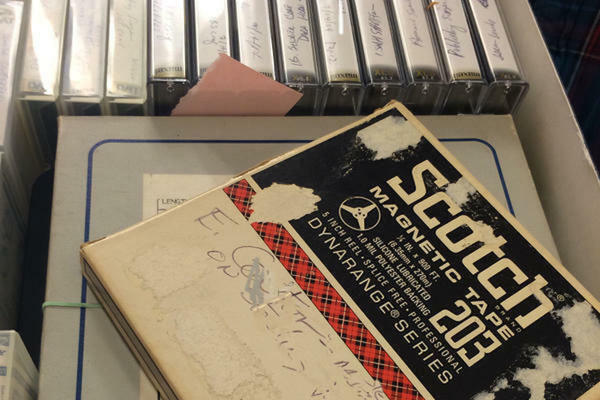

But a different Avrom Sutzkever emerges in the archival recordings from the Frances Brandt Online Yiddish Audio Library. Sutzkever made frequent visits to the Jewish Public Library in Montreal, where he found old friends and met new ones. There was a community of refugees and immigrants in Montreal, a community who understood his experiences and who had even shared them. The Yiddish writer Abraham Karpinowitz, in a talk comparing the writing of Chaim Grade and Sutzkever at the library, spoke to the audience in a kind of shorthand, the language of intimates. “Geboyren iz sutzkever in smargon,” he said. “A kleyn shtetl nebn vilne. Vilner gedenken di shtetl.” (“Sutzkever was born in Smargon, a small shtetl near Vilna. Vilners remember the shtetl.”) And the audience gathered in the room remembered.

Karpinowitz was Sutzkever’s friend and contemporary. In his inimitable, nostalgic voice, he recalls Sutzkever’s childhood, contrasting his upbringing in Siberia, and his nostalgic attachment to snow, with the autumnal beauty of Vilna. Karpinowitz ends by introducing us to Sutzkever the romantic hero and the lover of the city of Vilna.

Liba Augenfeld was the moderator of many of the events at the Jewish Public Library. In her introductory remarks at one event, she explains her history with Sutzkever. Her story begins precisely where Karpinowitz ended: with Sutzkever as an adolescent poet. She describes specific moments when she heard him speak: as a young girl at school, in the Vilna Ghetto, and in the forests outside the city. Her tone of voice—the neutral tone of a professional introduction—belies the intimacy of her words, describing a personal encounter with greatness. Her Sutzkever is brilliant and awe-inspiring, but he isn’t yet the hero of a national myth. He is an actual human being, a person she feels privileged to know.

Lastly, we hear Sutzkever himself. It’s May of 1959. Sutzkever has been asked to speak about his poetic autobiography. He understands that many see him as a hero, see him as a figure of resistance and as the preserver of a national culture. Many in the audience see him that way. Clearly uncomfortable with the role, Sutzkever deftly deflects the topic. He tells an anecdote about the arrival of a great rabbi, the zaddik hador, the most righteous of his generation, in Vilna. And when the anecdote is over, the audience, pleased to have heard the story, and to have heard it from their own zaddik hador, bursts into applause. It’s an incredible moment, one that underscores Sutzkever’s unique ability to blend the disparate strands of Yiddishkeit, to mix the sacred, the historic, and the poetic into a single utterance. It is a powerful introduction to Sutzkever’s equally powerful reflections on the way his life and poetic mind mingle.

A consistent theme emerges from the words of the three speakers. We often think of Sutzkever as a poet of memory, and of loss as his defining theme. Yet he was equally a poet of place, setting, the seasons: the meeting places of the natural and unnatural worlds. And always, there is snow.

And I do see the boy, Abrashe Sutzkever, dragging a sled so he can storm down the mountains around Vilna and have the snow envelop him in its floury dust.

I see him swimming from one bank of the Vilnia River to the other. I also see Sutzkever standing beside the door of the Strashun Library in the courtyard of the Great Synagogue, where we all used to go to drink wisdom and try to comprehend the unknowable world.

I’ve already mentioned how, as a youth, a great snowy land lured him with its lofty slogans about equality and justice. Sutzkever even cajoled me to run with our comrades to the east. But the lord of Yiddish poetry stood at his side and protected him so that he could serve our national literature. Protected him, so that he would not perish in a Soviet gulag, during Stalin’s horrific reign over the Red Empire.

Sutzkever, from his earliest days, was in love with snow. It is no wonder that he even wove into his Israel poems images from the Siberian landscape, where he spent his youth. In his verses, he longed for the hut in the Siberian taiga, where he spent his childhood.

Sutzkever was born in Smargon, a small shtetl beside Vilna. Those who come from Vilna will remember the shtetl. During World War I, his parents left the shtetl and migrated to Siberia, to wait out the hardship and hunger that the war had brought to the Jewish settlements.

Later, Sutzkever breathed the cold fresh autumn of the taiga into his poems—poems which, afterward, Elkhonen Vogler, his friend from the Young Vilna group, described as blooming with roses and cherry trees and fruit.

But his longing for the landscape of his childhood could not overcome his attachment to his hometown of Vilna. And if he had already chosen his path in life, to be a poet, it could only have come true for him in that city where beauty lay on every cornerstone.

My friends, my Vilna brothers, you still perhaps remember as I do, that even the nightingales in Vilna sing—still today—more beautifully than in any other city in our wide world. The most auspicious time for them is the early autumn. In Vilna, where mountains and valleys and forests and meadows encroach upon the city itself, autumn days are more colorful than anywhere else.

And from the castle mount there fall golden leaves. In Telatnik Park, brown chestnuts lie scattered, shining like the eyes of young horses. And the nearby suburb of Karolinka has its green fields and forests, its streams and fish ponds.

But Sutzkever lived in two little rooms just outside Shnipeshok, a provincial suburb of Vilna—two tiny little rooms, together with his mother.

The apartment was in an old wooden house, with the windows left open to the orchard and to the Vilnia River. Through these windows the future poet saw the entire world—the entire world veiled with the purest snow his imagination could conceive of and shadowed with spring’s first blossoming of the apple trees above Shnipishok on the way to the golden fields of rye.

…

And back, my friends, to Vilna, to the Jerusalem of Lithuania, and Sutzkever’s place therein.

There, in the streets of our hometown, goes a young man with a thick, dark blond head of hair and a pair of bright blue eyes, lanky and slender, a smile on his lips.

Oh, how the girls gawk at him as he walks past!

He is hiking to the Shishkine mountains over Shnipeshok, in order that he might feel and see the whole city of Vilna at his feet.

Vilna spread herself out before his eyes with all of her beauty, with all of her charm. Like a lover, the Jewish city lay in its green, flower-strewn bed, and waited for the poet Avrom Sutzkever to take her in his arms and whisper his poetic words to her.

און דעם ייִנגל אַבראַשקע סוצקעװער זע איך יאָ, װי ער שלעפּט אונטער זיך אַ שליטעלע כּדי אַראָפּצושטורעמען פֿון די װילנער בערג, אַז דער שניי זאָל אים פֿאַרהילן אין אַ מעליקן שטויב.

אי זע אים יאָ שװימען פֿון איין ברעג װיליע צום אַנדערן. אי זע איך סוצקעװער, װי ער שטייט נעבן דעם טיר פֿון דער סטראַשון ביבליאָטעק אויפֿן שולהויף, װוּ מיר אַלע זײַנען געגאַנגען טרינקען חכמה און פּרוּװן באַגרײַפֿן די אומבאַקאַנטע װעלט.

כ′האָב שוין דערמאָנט, װי אַ גרויס פֿאַרשנייט לאַנד האָט געמאַניעט אין זײַן יוגנט מיט דערהויבענע לאָזונגען װעגן גלײַכקייט און גערעכטיקייט. אויך סוצקעװער האָט מיר שטאַרק צוגערעדט צו לויפֿן מיט חבֿרים אויף מזרח. אָבער דער האַר פֿון דער ייִדישער דיכטונג איז געשטאַנען אויף זײַן זײַט, און אים אָפּגעהיט פֿאַר אונדזער נאַציאָנאַלער ליטעראַטור. אָפּגעהיט ער זאָל נישט דאַרפֿן אומקומען אין אַ סאָװעטישן לאַגער, בית די גרויליקע סטאַלין־יאָרן אין דער רויטער אימפּעריע.

און סוצקעװער איז פֿון זײַן יוגנט געװען פֿאַרליבט אין שניי. אַ װוּנדער! אַפֿילו זײַן ישׂראל לידער האָט ער אויסגעװעבט אויפֿן פֿאָן פֿון דער סיבערער לאַנדשאַפֿט, װוּ ער האָט פֿאַרבראַכט זײַן קינדהײַט. ער האָט געבענקט אין זײַנע שורות נאָך דער כאַטע אין דער סיבערער טײַגע, װוּ עס זײַנען פֿאַרבײַ זײַנע קינדער־יאָרן.

געבוירן איז סוצקעװער אין סמאַרגאָן, אַ קליין שטעטל נעבן װילנע. װילנער געדענקען די שטעטל. אין די יאָרן פֿון דער ערשטער װעלט מלחמה, האָבן זײַנע עלטערן פֿאַרלאָזן דאָס שטעטל און אַװעקגעװאַנדערט אַזש קיין סיביר, איבערװאַרטן די נויט און הונגער, װאָס דער קריג האָט געבראַכט אין די ייִדישע ישובֿים.

דער קאַלטן פֿרישן אָטעם פֿון דער טײַגע האָט סוצקעװער שפּעטער אַרײַנגערויכט אין זײַנע לידער. לידער װאָס האָבן זיך צעבליט דערנאָך מיט רויזן און קאַרשנבוימען און פּירות, װי עס האָט דערציילט זײַן חבֿר פֿון דער יונג־װילנע גרופּע, אלחנן װאָגלער.

אָט די בענקשאַפֿט נאָך דער לאַנדשאַפֿט פֿון זײַנע קינדער־יאָרן, האָט נישט געקאָנט גובֿר זײַן די צוגעבונדנקייט צו זײַן היימשטאָט װילנע. און אויב ער האָט שוין אויסגעקליבן זײַן װעג אין לעבן צו זײַן אַ דיכטער, האָט עס געקענט פֿאַר אים זײַן בלויז אין דער שטאָט, װוּ די שיינקייט איז געװענ אויסגעלעגט אויף יעדן װינקל־שטיין.

מײַנע פֿרײַנט, מײַנע װילנער ברידער, אפֿשר געדענקט איר נאָך אַזוי װי איך, אַז אַפֿילו די נאַכטיגאַלן אין װילנע זינגען דאָרט ביז הײַנט שענער װי אין אַנדערער שטאָט אויף דער גרויסער װעלט. װײַל די סאַמע גינסטיקע צײַט פֿאַר זיי איז דער פֿרי־האַרבסט. אין װילנע, װוּ בערג און טאָלן און װעלדער און פּאַלאַנעס [פּאָליאַנעס] קומען אַרײַן ביזן סאַמע שטאָט, זײַנען די טעג פֿאַרביקערע װי ערגעץ אַנדערש־װוּ.

און פֿון שלאָסבאַרג שיטן זיך גאָלדענע בלעטער, אין שטאָט גאָרטן אין טעלאַטניק ליגן צעװאָרפֿן ברוינע גלאַנציקע קאַרשטאַנקעס װי אויגן פֿון יונגע פֿערד. און די פֿאָרשטאָט קאַראָלינקע לעדאַרײַ מיט אירע גרינע פֿעלדער און װעלדער מיט אירע טײַכלעך און סאַזשעלקעס.

און סוצקעװער האָט געװוינט אין שניפּעשאָק אין צװיי קליינע צימערלעך נישט אין דער אָקרוזשנע. אָבער קליינע, קלייניקע צימערלעך צוזאַמען מיט זײַן מאַמען.

די װוינונג איז געװען אין אַן אַלטער הילצערנער הויז מיט די פֿענצטער צעפֿאַרלאָזן אין סאָד און צו דעם װיליע טײַך. דורך אָט דעם פֿענצטער האָט דער קומענדיקער דיכטער געזען די גאַנצע װעלט––די גאַנצע װעלט באַשנייט מיט דעם ריינסטן שניי פֿון זײַן דימיון און באַשאָט מיט דעם ערשטן פֿרילינג־בלי פֿון די עפּל־בוימער ארויף שניפּעשאָק אויפֿן װעג צו די גאָלדענע קאָרנפֿעלדער.

----

און װידער, מײַנע פֿרײַנט, צו װילנע, צו ירושלים ד′ליטע, און סוצקעװער אין איר.

אָט גייט איבער די גאַסן פֿון אונדזער היימשטאָט אַ יונג בחורל מיט אַ געדיכט אויף טונקעל־בלאָנדער טשופּרינע און אַ פּאָר העלע בלויע אויגן, אַ דינער, אַ שלאַנקער, מיט אַ שמייכל אויף די ליפּן.

און אַלע מיידלעך קוקן זיך אום װען ער גייט פֿאַרביי.

ער שפּאַנט צו די שישקינע בערג אַרויף שניפּעשאָק, כּדי צו פֿילן און זען די גאַנצע שטאָט װילנע בײַ זײַנע פֿיס.

װילנע האָט זיך אויסגעשפּרייט פֿאַר זײַנע אויגן אין אירע שיינקייט, אין איר גאַנצן חן. װי אַ געליבטע, די ייִדיש שטאָט געלעגן אויף איר דיכטער אבֿרהם סוצקעװער, ער זאָל איר נעמען אין זײַנע אָרעמס, איר שעפּשעט אין זײַן פּאָעטיש װאָרט.

In 1941, after the Soviets occupied Vilna, I had the opportunity to hear Sutzkever read his own poetry. At that time I was still a pupil in the senior class of one of Vilna’s high schools, the Yiddish-speaking Real Gymnasium. True, it was not called then the Yiddish Real Gymnasium, but rather the Fortieth State Gymnasium. The director, the famous teacher Mira of the eponymous poem Sutzkever would later write, reserved an afternoon in the school for the young poet Avrom Sutzkever to come read us poems from his recently published book, Valdiks [From the Forest].

Even then, the poems sounded so fresh. We were used to poetry sounding entirely different. This was full of new, trembling tones, new expressions that we had never heard before.

--

At the end of April 1943, a literary evening with the innocent name “The Spring Season in Yiddish Literature” took place in the Vilna Ghetto. Sutzkever read a poem, “A nem ton dos ayzn” ["Take Hold of the Iron"]—a poem that electrified the audience. The hall was over-full, packed, there was nowhere even to stand. It was the young people, especially, who filled every corner. “Vos mir friling, ven mir friling”:—“Whatever spring, whenever spring”—we all knew it celebrated the first of May [International Workers’ Day], and that the poem was written specifically in honor of the recently crushed uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto.

The impression it made was tremendous. The poem was an open call to take up arms against the Nazis. An open call to revolt. And we took the call very seriously.

--

Life in the Narotshe woods was very hard for us Jewish kids from Vilna. One compensation for it, though, was that we had the privilege to hear Avrom Sutzkever read his poetry. He, accompanied by his wife, Freydke, and Shmerke Kaczerginski, would go to the forest huts where Jews had camped out, and they made every visit into a holiday.

I don’t know whether you can imagine what a blissful, elevated moment we experienced when we heard his wonderful poem “Kol nidrey” [the name of the service that begins Yom Kippur] for the first time, and also the poem “Mayn mame” [“My Mother”], which we used to call “Di dray royzn” [“The Three Roses”]. Later, when the famous poet Boris Pasternak translated it into Russian, he also titled it “Three Roses.”

I also remember when, in March 1944, Sutzkever came to say goodbye to us. They brought him away to Moscow, so that he could serve there as the representative of the murdered Jews of Vilna. Just after the war, when we were still in the DP camps, we followed Sutzkever when he came to give testimony at the Nuremberg trials. We felt great pride and respect, as through him, our voice, too, would be heard throughout the world.

אין 1941, װען די סאָװיעטן האָבן געהאַט באַזעצט װילנע, האָב איך געהאַט דאַן אַ געלעגנהײט צו הערן סוצקעװער אַלײן, לײענען זײַן פּאָעזיע. איך בין נאָך דאַן געװען אַ תּלמידה אין לעצטן קלאַס פֿון דער ייִדישער רעאַל גימנאַזיע אין װילנע. אמת, דאַן האָט זי שױן ניט געהײסן ייִדישע רעאַל גימנאַזיִע, נאָר די 40טע מלוכישע גימנאַזיִע. און דער דירעקטאָר, די באַרימטע לערערין מירע פֿון סוצקעװערס שפּעטערדיקער פּאָעמע, האָט אײַנגעהאַלטן אין אױדיטאָריע פֿון גימנאַזיִע אַ נאָכמיטאָג ביז װעלכן דער יונגער פּאָעט אַבֿרהם סוצקעװער האָט געלײענט פֿאַר אונדז די לידער פֿון זײַן נײַ דערשינענעם ביכל ״װאַלדיקס.״

שױן דאַן האָבן די לידער געקלונגען אַזױ פֿריש. גאָר אַנדערש מיר זײַנען געװױנט געװען פּאָעזיִע זאָל קלינגען. פֿול מיט נײַע צאַפּלדיקע טענער, נײַע אױסדרוקן, װאָס מיר האָבן נאָך ביז דאַן ניט געהאַט געהערט.

--

סוף אַפּריל 1943 איז אין געטאָ פֿאָרגעקומען אַן אָװנט װאָס האָט געטראָגן דעם אונשולדיקן נאָמען ״פֿרילינג אין דער ייִדישער ליטעראַטור.״ סוצקעװער האָט דאַן געלײענט אַ ליד, ״אַ נעם טאָן דאָס אײַזן.״ אַ ליד װאָס האָט עלעקטריזירט דעם עולם, דער זאַל איז געװען איבערפֿול, געפּאַקט, סיז ניט געװענט װוּ צו שטײן. ספּעציעל די יוגנטליכע האָבן אױסגעפֿילט יעדן װינקל. ״װאָס מיר פֿרילינג, װען מיר פֿרילינג,״ אַלע האָבן מיר געװוּסט, אַז דאָס פֿײַערט מען דעם ערשטן מײַ, און אַז דאָס ליד איז ספּעציעל געשריבן געװאָרן אין כּבֿוד פֿון דעם אָקאָרשט אונטערגעדריקטן אופֿשטאַנד אין װאַרשעװער געטאָ.

דער אײַנדרוק איז געװען אומגעהױער. דאָס ליד איז געװען אַן אָפֿענע אַרױסרוף צום קאַמף קעגן די נאַציס. אַן אָפֿענע אַרױסרוף צום רעװאָלט. און מיר האָבן דעם אַרױסרוף דאַן זײער ערסנט גענומען.

--

דאָס לעבן פֿון די נאַראָטשער װעלדער איז פֿאַר אונדז ייִדישע יוגנטלעכע פֿון װילנע געװען זײער שװער. אײנס פֿון די פֿאַרגיטיקונגען איז געװען, װאָס מיר האָבן געהאַט די זכיִע צו הערן אַבֿרהם סוצקעװער לײענען זײַן פּאָעזיִע. ער אין באַגלײטונג פֿון פֿרײדקען און שמערקען פֿלעגן גײן איבער די װאַלד־שטיבלעך װוּ ייִדן האָבן זיך געפֿונען, און יעדער װיזיט אַזאַ איז פֿאַרװאַנדלט געװאָרן אין אַ יום-טובֿ.

איך װײס ניט, אױב איר קענט זיך איצט פֿאָרשטעלן, װאָס פֿאַר אַ יום-טובֿדיקע דערהױבענע מאָמענטן מיר האָבן דאַן איבערגעלעבט, װען מיר האָבן צום ערשטן מאָל געהערט די װוּנדערבאַרע פּאָעמע ״כּל נדרי״ און אױך דאָס ליד ״מײַן מאַמע,״ װאָס צװישן זיך פֿלעגן מיר עס רופֿן ״די דרײַ רױזן.״ שפּעטער, װען דער באַרימטער פּאָעט באָריס פּאַסטערנאַק האָט עס איבערגעזעצט אױף רוסיש, האָט אױך ער עס גערופֿן אונטערן נאָמען ״דרײַ רױזן.״

איך געדענק אױך װי אין מאַרץ 1944 איז סוצקעװער זיך געקומען געזעגענען מיט אונדז. מען האָט אים און פֿרעדיקען אַריבערגענומען קײן מאָסקװע, כּדי ער זאָל דאָרט זײַן דער פֿאָרשטײער פֿון דעם אומגעקומענעם װילנער ייִדנטום. שוין נאָך דער מלחמה, װען מיר האָבן זיך נאָך געפֿונען אין די דיפּי לאַגערן, האָבן מיר נאָכגעפֿאָלגט סוצקעװערס, עדות זאָגן אױפֿן נירענבערגער פּראָצעס, מיט גרױס שטאָלץ און פֿאַרערונג, װײַל מיר האָבן געפֿילט, אַז דורך אים, װערט אױך אונדזער שטים געהערט אין דער װעלט.

My friend Melekh Ravitch, who knew in advance what I would say, mentioned earlier that I would, in today’s conversation, in today’s lecture, provide an autobiography of myself. I do not know if this will be that, for I am afraid of speaking too much about myself, about my poetry, and I’m wary of stumbling into a tone that’s inappropriate for me.

I remember that on the eve of the Second World War there was a conference of rabbis in Vilna. Chaim Grade described it in his most recent book. I remember, though, something said by the Chofetz Chaim, from Radin, when he was invited to open the conference, which he had not wanted to do. They said to him, “What do you mean! You are the tzadik-hador [most righteous of the generation]! So why do you say, ‘I am a sinful Jew?’” People attempted to persuade him with all kinds of pieties, and he dismissed them all. Later, they said to him, “But you are the oldest of all of us!” Oh! That he couldn’t deny and, hunched over, he went up to the podium, and he recited a verse from the bible, a forceful verse. He began thus: “In Exodus there is a verse, which was applicable when Jews offered sacrifices. At that time, when the priest or whomever went up to the podium, he would apparently go up dressed in light clothing, and there was a prescription for him” ‘You shall not go up by steps to my altar, that thy nakedness not be uncovered.’” The Chofetz Chaim explained the verse: You should not rise to the altar with your virtues lest everyone see your nakedness.

Dear friends, I do not want to speak about myself, about my virtues. Therefore, I will not—I would not—tell you about my poetic merits while speaking on the theme, “My life and my poetry.” As much as possible, I want to objectively bring you closer to the laboratory of my creation and the biography of my poetry. Because the true biography of a poet’s life—that is his creation, just as the biography of the prophet is his prophecy. His whole life, the poet immunizes himself against eternity, so to speak. And though it seems he immunizes his paper and not his body, his body and his soul are in the paper, and the paper causes him endless pain. In order for the poet to reach his goal, the diseases must be accepted, they must affect the reader, and as a result, art receives immunity against forgetting, and against the poet’s own passing.

Two events strongly affected my life in my early years. First, my childhood in Siberia. My first seven, eight years in the far north, where my mother tongue—though people have written that I am an expert in Yiddish—I can divulge the secret that the first language I spoke in my childhood was Kyrgyz. Because there I found myself among Kyrgyz people, played with them. And I learned the local language.

And the scenes in Siberia, in my earliest childhood: a hut in the vast steppe. Beyond, the Irtysh river, covered in snow. The prolonged cry of a wolf carries across the steppe. My father, in the half-darkness of the hut, plays a Jewish melody on his red violin, and, with all my senses, I absorb the sounds of the fiddle as they mix with the cry of the wolf, and it seems as if I can hear young doves hatching from their eggs on the roof. And at dawn, as the sun rises from the snow as if it were dressed in a fiery pelt, I, six years old, come out, meet the day, and I see in the snow the tracks of an animal. And in the distance, I see the animal running, and its breath curls upward into the frost, into the sky. And another breath rises: a breath from a chimney, upward. And my own small breath climbs, climbs. And from these three breaths, a tent spreads over the steppe.

Or at night, when the moon lies there, frozen, its nose in the snow, and the snowman which I have only just shaped, begins—the more I look at him—to appear as if he were dancing opposite the stars.

These scenes, diamonds, which entered my soul during my earliest years, sparkle for me and in me during all darknesses. They comforted me and gilded even in the ghetto. Their singing lightness always gave me pleasure, and when I was ten years old, by then in Vilna, those Siberian sounds and colors began to demand I free them, give them words. I should give them words as sustenance. And certainly, more intuitively than consciously, I then began to feel the pronouncement of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, that he who has something to write, but does not write, is like one who murders his own children. And so was born my first epic poem, Siberia, whose reflection can be found in almost all of my later works, up to this day—even in Secret City [Sutzkever’s epic poem about an attempt to survive the destruction of Vilna], my childhood coos and glitters.

מײַן חבֿר מלך ראַװיטש, װאָס ער װײסט פֿון פֿאָרױס װאָס איך װעל זאָגן, האָט פֿריִער געזאָגט, אַז איך װעל געבן אין מײַן הײַנטיקן שמועס, מײַן הײַנטיקן רעפֿעראַט, אַן אױטאָ־פּאָרטרעט פֿון זיך. װײס איך ניט, צי דאָס װעט זײַן אַזױ, װײַל איך האָב מורא צו רעדן צו פֿיל װעגן זיך, װעגן מײַן דיכטונג, און ניט אַרײַנצופֿאַלן אין קײן טאָן װאָס איז ניט פּאַסיק פֿאַר מיר.

איך דערמאָן זיך, ערבֿ דער צװײטער װעלט מלחמה, איז פֿאָרגעקומען אין װילנע דער צוזאַמענפֿאָר פֿון די רבנים. חיים גראַדע באַשרײַבט עס אין זײַן לעצטן בוך. איך געדענק אָבער אַ װאָרט פֿון דעם חפֿץ חיים, פֿון ראַדין, אַז װען מען האָט אים געבעטן, ער זאָל עפֿענען די פֿאַרזאַמלונג, האָט ער ניט געװאָלט. האָט מען אים געזאָגט, "ס'טײַטש! איר זײַט דאָך דער צדיק הדור. טאָ װאָס רעדט איר, 'איך בין דאָך אַ זינדיקער ייִד?′″ אַזױ האָט מען אָנגעהױבן אים אײַנצורעדן מיט כּל מיני פּיטעטן און ער האָט עס אַלץ אָפּגעװאָרפֿן. שפּעטער האָט אים געזאָגט, "איר זײַט דאָך דער עלצטער פֿון אונדז." אָ ־ דאָ האָט ער ניט געקענט לײקענען און געבױגנערהײט איז ער אַרױף אױף דער בינע, און ער האָט געזאָגט אײן פּסוק, אַ גװאַלדיקן פּאָסק. ער האָט געזאָגט אַזױ: "פֿאַראַן אין שמות, אַ פּסוק, װאָס איז גילטיק געװען אַ מאָל בעת ייִדן האָבן געמאַכט מזבחות איז דעמאָלט, װען עס פֿלעגט אַרױפֿגײן דער כּהן צי װער...פֿלעגט ער קענטיק גײן אָנגעטאָן אין לײַכטע קלײדער, איז געװען פֿאַר אים אַן אָנזאָג, ″וְלֹא-תַעֲלֶה בְמַעֲלֹת, עַל-מִזְבְּחִי: אֲשֶׁר לֹא-תִגָּלֶה עֶרְוָתְךָ, עָלָיו″ זאָלסט ניט אַרױפֿגײן אױף דער בינע אױף דער מזבח, אין דער הױך אױף די טרעפּ, צום מזבח, מע זאָל ניט אַרױסװײַזן דײַן נאַקעטקײט. האָט עס דער חפֿץ חיים פֿאַרטײַטשט אַזױ: זאָלסט ניט אַרױפֿגײן מיט דײַנע מעלות אױפֿן באַלעמער, מע זאָל ניט זען דײַן נאַקעטקײט.

װיל איך ניט, מײַנע טײַערע פֿרײַנט, רעדן װעגן זיך, װעגן מעלות. דעריבער װעל איך־־ װאָלט איך־־ ניט געװאָלט בײַם רעדן אױף דער טעמע "מײַן לעבן און מײַן ליד," דערצײלן װעגן מײַנע פּאָעטישע מעלות. נאָר בלױז װי װײַט מעגלעך אָביעקטיװ דערנענטערן אײַך צו דער לאַבאָראַטאָריע פֿון מײַן שאַפֿונג און צו דער ביִאָגראַפֿיע פֿון מײַן דיכטונג. װײַל די אמתע ביִאָגראַפֿיע פֿון אַ דיכטערס לעבן, דאָס איז זײַן שאַפֿונג, װי די ביִאָגראַפֿיע פֿון דעם נבֿיא איז זײַן נבֿואה. אַ גאַנץ לעבן שטעלט זיך דער פּאָעט, אײביקײט־פּאָקן, װאָלט איר געזאָגט. און כאָטש ער שטעלט זײ, דאַכט זיך, ניט אױף זײַן לײַב, נאָר אױף פּאַפּיר, איז אָבער זײַן לײַב און זײַן נשמה אינעם פּאַפּיר, און דאָס פּאַפּיר טוט אים אומענדלעך װײ. כּדי דער פּאָעט זאָל דערגרײכן זײַן ציל, מוזן די פּאָקן אָננעמען, מוזן זײ װירקן אױפֿן לײענער, און במילא באַקומט די קונסט אַן אימוניטעט קעגן פֿאַרגעסנקײט און קעגן דעם דיכטערס אײגענעם פֿאַרגאַנג.

צװײ געשעענישן האָבן שטאַרק באַװירקט מײַן לעבן אין די פֿריִע יאָרן. די ערשטע, מײַן קינדהײט אין סיביר. מײַנע ערשטע זיבן, אַכט יאָר אין װײַטן צפֿון װוּ מײַן מאַמע־לשון, כאָטש מע האָט געשריבן װעגן מיר, אַז איך בין אַ גוטער ייִדיש קענער, מעג איך אָבער אױסזאָגן דעם סאָד, אַז מײַן ערשטע לשון װאָס איך האָב גערעדט אין מײַן קינדהײט איז געװען קירגיזיש. װײַל איך האָב זיך געפֿונען צװישן קירגיזן, מיט זײ זיך געשפּילט. און זיך אױסגעלערנט דעם דאָרטיקן לשון.

און די בילדער אין סיביר, אין מײַן פֿריִער קינדהײט ־־ אַ כוטער אין װײַטן סטעפּ. הינטערן אירטיש, פֿאַרשנײט. איבערן סטעפּ טראָגט זיך אַן אױסגעצױגענער געװױ פֿון אַ װאָלף. דער טאַטע אין דער האַלב־טונקעלקײט פֿון כוטער, שפּילט אױף זײַן רױטער פֿידעלע אַ ייִדישן ניגון, און איך נעם אױף מיט אַלע חושים, די קלאַנגען פֿונעם פֿידל װאָס מישן זיך מיטן געװױ פֿונעם װאָלף, און עס דאַכט מיר, אַז איך הער אױפֿן בױדעמל, װי די טײַבעלעך פּיקן זיך אױס פֿון די אײער. און פֿאַרטאָג די זון גײט אױף פֿון שנײ אַרױס װי אָנגעטאָן אין אַ פֿײַערדיקן פּעלץ, איך, אַ זעקס־יעריקער, קום אַרױס, באַגעגענען דעם טאָג, און איך זע דעם שנײ, די שפּורן פֿון אַ חיה. און פֿון װײַטן זע איך װי די חיה לױפֿט, און איר אָטעם קרײַזלט זיך אַרױף אינעם פֿראָסט, אין די הױכן. און נאָך אַן אָטעם גײט אױף: אַן אָטעם פֿון אַ קױמען, אַרױף. און מײַן אײגענער קלײנער אָטעם קלעטערט, קלעטערט. און פֿון די דרײַ אָטעמס װערט אױסגעצױגן איבערן סטעפּ אַ געצעלט.

אָדער בײַנאַכט װען די לבֿנה ליגט אַ פֿאַרפֿראָרענע מיטן נאָז אין שנײ, און דער שנײמענטש װאָס איך האָב אָקערשט אױסגעקנאָטן, איז װאָס מער איך קוק אױף אים, דוכט מיר זיך אױס, אַז ער טאַנצט אַנטקעגן די שטערן.

די דאָזיקע בילדער, דימענטן, װאָס זײַנען אַרײַן די ערשטע יאָרן אין מײַן נשמה, פֿינקלען פֿאַר מיר און אין מיר דורך אַלע פֿינצטערנישן. זײ האָבן מיר געטרײסט און באַגאָלדיקט אױך אין געטאָ. זײער זינגענדיקע ליכטיקײט פֿאַרשאַפֿט מיך תּמיד הנאה, און װען איך בין אַלט געװען אַ יאָר צען שױן אין װילנע, האָבן יענע סיבירער קלאַנגען און פֿאַרבן גענומען מאָנען אין מיר אַ תּיקון, איר זאָלט זײ געבן װערטער. איר זאָלט זײ געבן צום עסן װערטער. און געװיס מער אינטויִטיװ אי באַװוּסטזיניק האָב איך דעמאָלט דערשפּירט דעם אָנזאָג פֿון רעב נחמן בראַצלעװער, אַז װער עס האָט װאָס צו שרײַבן, און ער שרײַבט ניט, איז געגליכן צו אײנעם װאָס דערהרגעט די אײגענע קינדער. און אַזױ איז געבױרן מײַן ערשטע פּאָעמע ″סיביר,″ װאָס אירע אָפּשטראַלן קאָן מען געפֿינען אין כּמעט מײַנע אַלע שפּעטערדיקע שאַפֿונגען ביז הײַנט צו טאָג, אַפֿילו אין געהײמשטאָט, פֿינקלט אַרײַן, װאָרקעט אַרײַן מײַן קינדהײט.