Fabulous Fashions: Bronx Bohemian Style

— Sasha B. Stern, the 2020-2021 Richard S. Herman Fellow.

Furs and lace, pearls and velvet, silk cravats and elaborate hats!

Early in 2020, we received a treasure trove of boxes overflowing with letters to and from Bertha Kling, whose Bronx salon was one of the key addresses of Yiddish New York in its early 20th century heyday. Among her correspondents were many emerging and full-fledged Yiddish literary celebrities. As the hip artistes of their time, Kling's penfriends left behind not just a legacy of Yiddish work, but copious photographic evidence of their dapper fashions and shining personalities. We were instantly bewitched.

The Bronx Bohemians, as we’ve been calling this circle, were a snazzy bunch. And their clothes—the ways they chose to present themselves—give us glimpses of who they were as people. As I am not the sort of person who can narrow down a photo’s year of origin by the shape of a collar, I spoke with textile historian and costume designer Professor Kiki Smith of Smith College, who lent her considerable expertise to this endeavor. Her insights appear throughout the piece below and reveal fascinating details of not just the pictured clothes, but also the Bohemians themselves—and the world around them.

As you read, look at these figures as the people they were: how do they hold their heads, and what do their gazes tell you? What does their fashion emphasize, and what image does it project? And, most importantly: how groovy are their hats?

Russian-born Lara Cherniavsky’s photos show her to be just as gregarious as her letters suggest—spoiler alert (for a future Bronx Bohemians post, that is), the appropriate descriptor here is very. In what is certainly an image from before the first World War, she poses with casual confidence and at the height of style. According to Prof. Smith, Cherniavsky’s coat, with its lavish shawl collar of fur, would have been cut in an almost square shape, draping ”beautiful, sumptuous fabric” down her figure. Her hat, more than anything else, shows just how savvy she was—the dark inner lining sets off her face to perfection. Cherniavsky knew she was being photographed and knew exactly how she wanted it to come out. There’s a real sensuality suggested in the richness of the fabrics, as befits a woman who was not only a renowned musician in her own right, but also drew fame as part of her husband Joseph’s globetrotting Yiddishe American Jazz Band—appearing in recordings, concerts, and even film scores. There’s no doubt that Lara Cherniavsky was a presence, and it’s easy to imagine that she might part crowds on the way home from the photographer’s.

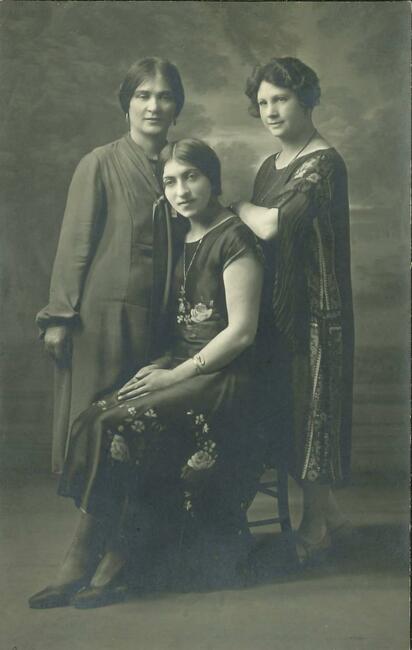

This shrayberin (women writers‘) triumvirate is a study in literary power. We hope that you’ve started to get to know Bertha Kling, the Yiddish singer and poet whose Bronx home became the epicenter of Yiddish artistic movements for decades. Her good friend Malka Lee spent her early years as a seamstress before lending her voice to the lyrical poetry that brought her great acclaim through more than fifty years of continuous publishing. And Ida Glazer’s renown began early: as our friend David Mazower wrote, by the time she was twenty, the Russian-born poet had ”published poems, joined the revolutionary movement, fled Tsarist police surveillance, emigrated to New York, moved back to Odessa, and returned once more to the United States.” This photo captures her in the earlier years of her literary fame, but already a veteran in Yiddish cultural movements. Our fashion expert believes the photo can’t have been taken any earlier than 1923, since Lee and Glazer’s dresses feature what would, before that time, be ”scandalously” exposed arms, short skirts, and shockingly skin-tone stockings. Of course, our friend Kling doesn’t leave herself out from the new fashion of the day—though her hemlines might be more conservative, her dress’s dropped waistline was a hallmark of 1920’s style. For all three, the loosening of the dress fit and shortening skirts point to the process of loosening restrictions around women’s style and societal expectations. Glazer and Lee, always hip to the scene, feature some very chic embroidery, while Kling’s monochrome is more refined. Standing together, matter-of-fact in their excellence, these three pose for a portrait that speaks to a closeness and solidarity among three greats of their Yiddish age.

Di Yunge, whose numbers included I. J. Schwartz (far left), Moyshe Leyb Halpern (top right), David Ignatoff (center) and Joseph Opatoshu (bottom), were young writers who arrived in the United States between 1906 and 1908, bringing the tides of poetic change with them. Although heavy overcoats and the occasional high, stiff collar place the photo in the mid-1910s to mid-1920s, these poets are not wearing the boaters or top hats of respectable young men of that era. Instead, they’re uniformly in soft, dented, felt fedoras—with variably-placed brims, no less—informal day hats for the working man. All this is fully in line with who Di Yunge were as poets: invested in aesthetic and focused on the poetics of the everyday. Joined arm to shoulder and meeting the camera with gazes that range from careless to cocky to mildly combative, Di Yunge conspicuously decline to aspire to high social class. They have no need to be posh, they’re cool: brimming (literally) with the ”studied negligence” of artistic youth. In the words of Prof. Smith, ”they take themselves SO seriously!"

Oh, that hat! Prof. Smith places this photo around 1910-1912, noting Fox’s ”great swooping hat,” her hair sitting low on the sides, and her lack of a high collar. This photo doesn’t capture the rest of what was ”probably a slender, vertical gown or dainty summer dress – a summer style”. Yet this delicate outfit, set off by a thin chain necklace, belies the mystery and artistry its wearer projects. We don’t know much about Ettie other than the fact that she was married to a Dr. Shmuel Fox, a poet among Di Yunge who became, of all things, a dentist. But by expression alone, Fox’s portrait imparts a graceful image with, in the words of Prof. Smith, a ”hint of seduction” from her dramatically shadowed eyes.

Malka Lee was married on June 4, 1922, just a year after immigrating to New York as a teenager from the small town of Monastrikh in what is now Ukraine, and every piece of her stunning outfit makes her a woman of the moment. She is unmistakably a bride, from cap to veil to the sheen on her pearls. Though we can’t see it in the photo, Lee’s commitment to modern fashion—and it was commitment: Prof. Smith found that her headpiece appeared in the newest Sears catalog that same year—makes it easy to imagine what she looked like walking down the aisle. The veil that falls from her pearl-beaded diadem would have draped soft, silk tulle into a long train, giving her a sense of ethereality. By contrast, though also made of soft silk, her dress would have been the ultimate modern statement: short for the time and quite tubular. A cross between a folkloric queen and red carpet star, Lee captivates as she peeks out from under her finery. Her gaze is deliberate. It is her wedding day, and she will write the ultimate portrait into being with the folds of her silks and the tilt of her head. Lee brought this will, skill, and purpose to the Sholem Aleichem Houses in the Bronx, where she lived for much of her adult life. She went on to publish six volumes of Yiddish poetry and a detailed memoir of her childhood.

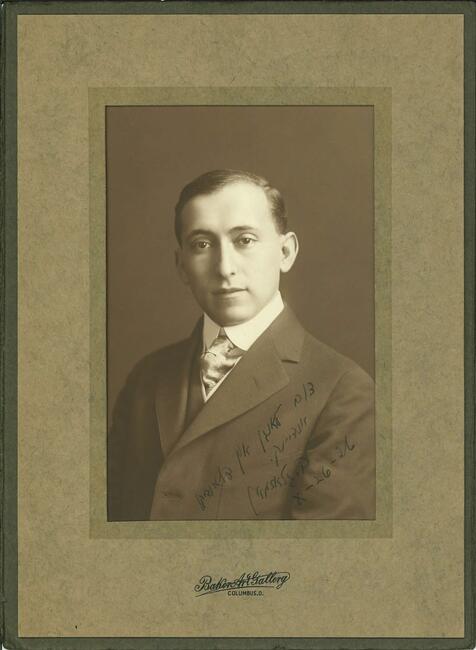

Despite his youth spent in religious and secular schooling in the Russian Empire, Borukh Glazman had a reputation as the "most American” of the American Yiddish literary circle. Perhaps to that point, his style is notable here for its departure from the glamor and, shall we say, artistic presentation of so many of the other photos in this series. A nice, professional shot shows an (aspirationally) upper class gentleman posed in his very nice wool suit, lovely tie, and starched collar. Everything about Glazman is upright and precisely placed. Because this image doesn’t mesh with the down-to-the-minute fashion trends of the more bohemian Bohemians, it’s hard to say at first glance what decade this photo hails from—the inscription dates it as 1926, but stylistically, it could just as easily be pre-WWI. On seeing him, Prof. Smith said that Glazman looked like “a guy who would wear a derby instead of a soft fedora”—someone polished, someone you could take home to your parents, someone who aspired to be more generally respectable than counter-cultural. He published at least nineteen novels throughout his long career.

We don’t know much about Lizzie Yumansky—just that “Lizzie“ was likely a nickname. Yet it’s easy to place this photo of Yumansky in the 1920s: she’s wearing a dropped waistline, a square neckline popular in the early part of the decade, and an iconic headwrap that likely covered a tight-fitting cap. ”Easy to place,” though, is by no means uninteresting: I was reminded by Prof. Smith that in this era, women’s eyes were a big deal, and this photograph demonstrates this handily. Yumansky's eyes are the first part of her face visible below her sash, illuminated and augmented by mascara, and her subtle smile does nothing to diminish their draw. Her dress's drape and monochrome contrasts with the structured angles and flashes of color from her accessories. They only enhance her eyes' intensity.

In our earliest photo of the series, Miriam Karpilove holds court as the first decade of the 20th Century slips into the second. One of the most widely published women of her Yiddish literary generation, she was famous for her serialized novels, many of which focused on the internal world and intimate relationships of women. It’s clear that she had a wealth of camaraderie to draw on! Karpilove is the most accessorized of the bunch, with spectacles, intricate embroidery, and a gilded comb tucked into her crown braid. Her companions dress in the typical manner of the day: high-waisted separates for the younger ladies, and a full-length dress with a contrasting lace collar for the more conservative elder. Far more than the clothes themselves, the way these women wear them tells us who they were. The pleats in their skirts do not merely flair, they flair onto one another’s laps, or are set off by the crisp white of a friend’s shirtwaist. They’ve discarded their walking jackets to spend time together indoors. They emanate comfort even as they pose. Karpilove and her friends feel like they could be in the next room, making music together, sharing confidences, debating the news of the day. Their amity jumps off the page.

Dora Shulner, born near Kiev, was a prolific Yiddish writer whose work on themes of revolution, romance, and loss was published in periodical pieces and full-length books alike in the American 1940‘s. But notably for this piece, her early life was spent working in a textile factory—once can imagine how she might take particular pride in her accessories and appearance with the full knowledge of how they were made. In this glamorous snapshot, the length of Shulner’s skirt speaks to the photo's historical context, and not just in terms of changing standards for appropriate hemlines. While in the previous decade, the fashionable skirt might reach mid-calf, in 1944, the United States was in the thick of the Second World War, and fabric was rationed. ”Because textiles needed to be conserved for overseas soldiers,” Prof. Smith told me, "women put their fashionable energy towards accessories” such as gloves, hats, and purses. Accordingly, these are the stars of Shulner’s outfit: velvet trim, white gloves, patterned clutch purse, and a truly fabulous dipped-brim hat.

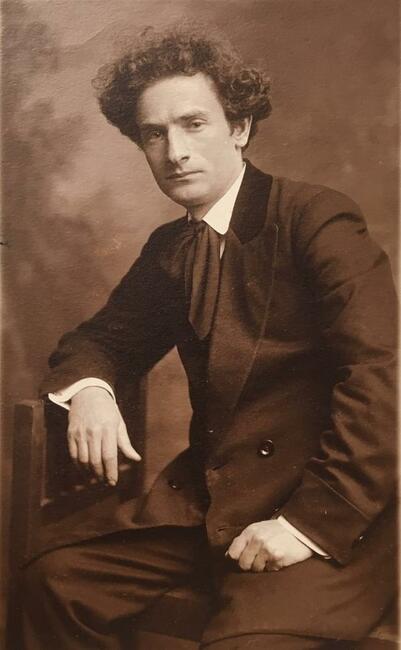

Goodness, what more can be said about Hirshbein that his hair does not say for him? Everything about this photo is lush and wild: his ”unkempt hairstyle“, his ”lavish ascot”... Prof. Smith even wondered if the dark collar on Hirshbein’s coat might be made of velvet! She placed the photo around the early 1910s, and the coat alone, with its fancy fabric and lower-than-proper overlap—not to mention the fact that it’s so informally open—shows Hirshbein‘s disregard for businesslike respectability. But would one expect the expected from a man who came into his literary and cultural fame from humble beginnings at his father’s water mill near Grodno? From the romantically blurred background to the artfully furrowed brow, every part of him screams that he is no traditional gentleman.

Bertha Kling and her Bronx Bohemian friends redefined Yiddish artistry, writing and (as we can clearly see) walking through the world with ultimate pizzaz. Copious thanks to Deborah Ramsden, granddaughter of Bertha Kling, from whose archives most of these photographs hail; the same to the illustrious Prof. Smith, for her illuminating insights and encyclopedic knowledge of the Sears catalogues of the 1920s. We hope this piece has brought the Bronx Bohemians to life, and perhaps inspired you to step out on the town in their honor—just don’t forget your hat!

The Bronx Bohemians blog is made possible with the support of the Lynn and Greendale families in memory of their aunt and mother, Zeva Greendale, and her special passion for yidishkayt.