March 2021: Handpicked

Each month, the Yiddish Book Center asks a member of our staff or a special friend to select favorite stories, books, interviews, or articles from our online collections. This month, we’re excited to share with you picks by Miriam Borden.

Miriam Borden is a doctoral student in Yiddish Studies at the University of Toronto, a Field Fellow with the Wexler Oral History Project, and a 2019–2020 Yiddish Pedagogy Program Fellow. She leads walking tours of Toronto’s historic Jewish neighborhood and is currently working on cataloguing a forgotten library of 2,000 Yiddish books found in a storage closet at the Morris Winchevsky Centre in Toronto. Some of these Handpicked selections come from that collection.

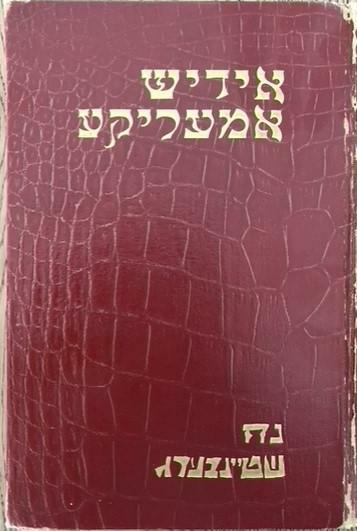

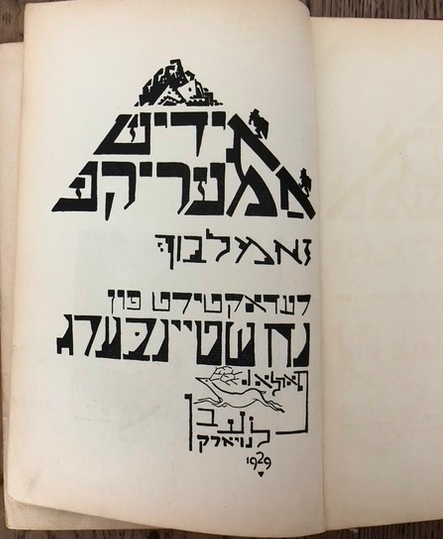

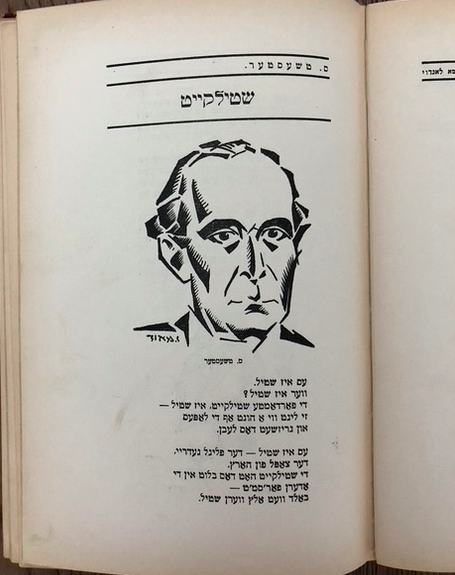

Idish amerike: zamlbukh (Yiddish America: Anthology), Edited by Noyekh Shteynberg

This 1929 anthology, bound in deep crimson faux-alligator skin, marbled endpapers, and gold lettering on the cover and spine, drips with the extravagance—and promise—of 1920s America. In true modernist style, the book features a rich interplay of image and text: among work by Moyshe Nadir, Moyshe Leyb Halpern, Hey Leyvik, and others, there are amazing art deco-style portraits of the writers, illustrations by Zuni Maud, photographs of work by Marc Chagall, and so much more. There’s a great irony to the lushness of this volume: it was published the year of the stock market crash that set off the Great Depression, throwing into sharp relief the hollowness of the lofty promises of di goldene medine.

Fun mayne teg (From My Days), by Shimon Nepom

Nepom (b. Elizavetgrad, Kherson, Ukraine, 1882; d. 1939, Toronto) was the most well-known of Toronto’s group of leftist poets, the Proletarian Poets. He was also a streetcar conductor for the city’s public transit system. His Depression-era cycle called Tramvay lider (Streetcar Poems) are dark and heavy, full of loneliness, loss and frustration: he describes his preoccupied and burdened passengers, the red flag-waving workers demonstrating in the streets, and his own despair at how his life has turned out. You get the sense that he suffered from FOMO: he was a poet who wanted to be a revolutionary.

“Coney Island,” a Sound Poem by Victor Packer

This 1940s recording features Packer, a brilliant oddball of the Yiddish radio waves, reading his own wild, zany, visceral, poem: a glimpse into a hot, packed beach full of half-dressed people. It takes some very strange turns, ending with an erotic encounter between a Jewish beachgoer and the water he’s splashing around in. Despite all the half-naked people, it’s the water—the coolness, the rhythm of the waves—that has this visceral effect on everyone—including the narrator. Follow along with a fabulous English translation by Henry Sapoznik.

Di goldene shtot: lider un poemes (The Golden City: Poems), by Arn Kurts

This collection, with a striking cover page illustrated by Yosl Cutler, is a somewhat reluctant love letter to New York. The city and its landmarks function as a frame for the human drama playing out within it: Kurts has poems that paint portraits of the working class (not only Jews), the chaotic sounds of the subway, and the metallic shine of the automat. He emphasizes the gulf of injustice separating the haves and the have-nots, especially in the throes of the Great Depression.

Lehaim yidish!, by Solomon (Shloime) Davidman

A short 52-page booklet—more like a scrapbook—containing letters of thanks, in both Yiddish and English, from libraries, synagogues, and individuals who purchased Shloime Davidman’s 1973 collection of essays and poems, A Song to Yiddish, which he published with financial help from friends. Davidman was a teacher of Yiddish, and it’s clear from these letters that his book was a labor of love—and as you read through them, you can’t help but smile from ear to ear. The old letterheads are the best part.

Annual Shlep From Detroit to Brooklyn for the Passover Seder

When Martin Broder’s family moved from Brooklyn to Detroit, his family began embarking on annual family trips back to Brooklyn each Passover. It was the one time of year everyone got together—and in this oral history excerpt, Martin provides extraordinary snapshots of the members of his family he’d see around the seder table every year.

Q&A

Miriam Borden talks to the Yiddish Book Center's communications editor, Faune Albert, about her Handpicked choices:

Faune Albert: Idish amerike is such a beautiful text! The artwork in it is captivating. I only wish I got to see the hard copy version you describe, which does indeed sound quite lush. I’m taking it from your description that you’ve had the opportunity to handle this book outside our digital collections. Can you say more about how and where you first discovered it? And can you also say more about the irony that the lushness of the volume exposes and how the work featured in the collection speaks to di goldene medine (American Dream)?

Miriam Borden: The idea of America has always captivated immigrants (usually, more than the reality of it has ever done). For more than two centuries, America has endured as a stable, unwavering symbol—but it contains an inherent contradiction, which is that it’s also incredibly unpredictable, malleable, and subject to interpretation and redefinition. Right now feels like another moment of reappraisal in America, a moment when it feels instructive for us to collectively look back at the history of this place and decide what kind of country we want it to be. I love this volume because the vision of America it puts forth is so clear and confident: this is Idish amerike—the America seen and interpreted through the eyes of Yiddish modernism. There’s a grandiosity (and maybe also a characteristically 1920s hubris) to the pieces in this anthology, and the alligator binding, the gold-edged pages—they mirror that extravagance.

There’s one short poem I love called “Yosemite Valley,” that goes, “What sculptor chiseled the granite mountain so sharp that no rain, no wind, could erase its ancient precision? Your waters roil and murmur with the primeval power of the earth, when all was fire. Your mountains join with the sky, gods from other eras, when worlds were born . . .”

I mean, talk about grandeur! There’s an irony, too, to the context in which I discovered this book, which was so far from the luxury it embodies: I found it in a box of forgotten Yiddish books disintegrating in a storage closet in Toronto. Later, it became clear that there were about 2,000 books in that closet, so for me, this book is part of the rediscovery of an entire Yiddish library nearly lost to history.

FA: Regarding your selection of Shimon Nepom’s poems, I read that a composer, Charles Heller, put music to them and even put out an album some years back, calling them his “Streetcar Songs.” I’m not sure if you have any musical background, but I’d be curious to know what you think about this and, as someone who’s familiar with these poems—you’ve translated some of them, no?—what you see in them that might lend them to song?

I’m also wondering if others in Toronto’s group of Proletarian Poets tended to write such dark and heavy works, or if Nepom’s is more unique in that regard?

MB: Nepom’s streetcar poems are, well, noisy: the wheels clang, the bell rings, the windows clatter, protesters on the street shout—he even describes the streetcar as chanting mournfully as it moves through the city. Maybe that’s where Heller’s musical instinct kicked in?

I don’t know if Nepom’s dark and heavy tone was necessarily unique; Yudica, the “sweatshop poet of Spadina Avenue,” writes in similarly bleak terms about factory life in Toronto. What makes his work stand out to me is how local and specific his images are. Toronto doesn’t tend to loom very large as a city of Yiddish poetry, but in Nepom’s work, it shines. Because he writes from the streetcar (an emblem of the city), he paints the city in terms every Torontonian will recognize: the metallic grind of the wheels, the way the sunlight glittering on the tracks contrasts with the mood of the long, dark winters. I recently shared a translation of one of Nepom’s poems with present-day public transit employees for their monthly newsletter; they got a kick out of the resonance!

FA: Victor Packer’s poem is so wild! I’d almost forgotten. It’s a bit of an interesting experience reading or listening to it during this pandemic, when many of us have been relatively isolated, just because it's all crowds and bodies, though as you note, ultimately it’s the water that has a visceral effect on people. I’d love to hear more about why you chose this poem and what your thoughts on it are. Does your familiarity with Packer extend beyond this?

MB: I discovered this poem while lesson planning for my Yiddish class: I wanted something that exemplified the musicality of the language, and Packer’s recitation definitely hits the mark. I knew of Packer from the Yiddish Radio Project but didn’t quite grasp the depth of his brilliance until I looked closely at this poem. It’s a totally wild ride that takes some very strange turns, especially playing with the kind of display of nudity that the beach allows: Packer invokes flesh/fleshiness, at one point calling the beach a “stockyard,” a grotesque image that defamiliarizes the whole experience of being at the beach. I chose this for two reasons: the first, of course, is that the pandemic has (literally) distanced us from the packed public spaces, and this poem reminds us what a sensory (and yeah, weird) experience they can be. And second, after a year spent largely indoors, I love Packer’s description of the raw encounter with nature—the unrelenting waves, the crash of ice-cold water, the angry current—and his suggestion that swimming in the ocean is less of a leisure activity and more like an attempt to tame the sea, to gain some control over nature, which of course we never do.

FA: I notice that a few of your selections (Shimon Nepom’s and Arn Kurts’ works specifically, though Idish amerike also might qualify) are from the Depression era. Was that intentional, and, if so, what about this time period and the work being produced during it intrigues you? Have you noticed any marked differences in the ways that Yiddish poets and writers approached writing about the working class during this time, or just generally?

MB: I do tend to spend a lot of time in the Depression, don’t I! Not intentional, no, but I suppose I’m continually moved by the deep disappointment of the era. This goes back to what I said about the context of Idish amerike: by the 1930s, it’s clear that America doesn’t measure up to people’s expectations; instead, America crushes them emotionally, mentally, and financially. Nepom, Kurts, and others writing in the 1930s captured the way the working class perceived this not only as a disappointment but as a failure of justice, especially for people who had risked everything for America and had nothing to show for it. Kurts has a remarkable poem called “Automat,” which I've translated—I'll share an excerpt below—where the poor and unemployed peer longingly, hungrily, into the automat:

Hands in feverish pockets,

Heads in cold collars,

Discouraged, licked.

In every disappointed chest

An automat beats and throbs—

Nickel-nickel-nickel-nick!

“Brother, can you spare a nickel?

I was in France, j’etais un soldat!”

— “Go, then, tell it

to the Horns & Hardarts — the lords/masters

of the mirrored nickel kit.”

In films from the 1930s the automat is a frequent site of social commentary on economic injustice; it’s also just one space Kurts evokes in this volume. I love the sense of atmosphere he provides. You can see the Chrysler Building; you can hear the cabarets of Harlem. In one poem Kurts invokes Jesus, Lincoln, and Lenin; another, “Nikldiker brut” ("Nickel Brutality"), is dedicated to Hyman Shandler, who, the poet adds, “was beaten to death by subway guards over a nickel.” “Subway” paints a sonic picture of the rhythm of the subway and thousands of feet that go “down, down down,” descending on the page like the stairs. In some ways, this is like the poetic complement to Lamed Shapiro’s short story “Nyu yorkish.”

FA: Lehaim yidish! is such a special find. How did you come across this one? Can you give us any insight into the impetus for or process of its creation?

MB: I found this while scanning the digital collections for material on love in/and Yiddish—and how fitting, because Shloime Davidman really loved Yiddish! As I learned from an article in this booklet, Davidman (1900–1975) worked as a butcher in Philadelphia, a launderer in the Bronx, and owner of a knish shop in Crown Heights—but his greatest joy was teaching Yiddish literature and history in Jewish schools in Chicago, Detroit, and Passaic and Paterson, New Jersey. I don’t know much about his 1973 A Song to Yiddish, but it’s clear that it made an impact on people. This booklet bursts with people’s appreciation for Davidman’s work. I love the idea that Davidman wasn’t content only to receive these thank you letters and keep them to himself. No, he was a businessman! And he saw an opportunity to reach out to his audience once again, tugging on heartstrings to get even more subscribers! So, naturally, the booklet opens with a plea to subscribe to A Song to Yiddish, followed by letters from enthusiastic recipients of the first printing. Gotta love that initiative! The booklet is also a glimpse into the Yiddish world of the 1970s: included is a thank you letter from Rubia Olf, wife of the folk singer Mark Olf. As a whole, it’s a beautiful, grassroots tribute to the impact of one dedicated guy who just really loved Yiddish.

FA: And why the oral history?

MB: It’s surreal to think this will be the second Passover many of us will be celebrating away from our families because of the pandemic. This excerpt jumped out at me for a simple reason: Martin’s memories about Passover are so anchored by the experience of being around his whole family. I love the way he says that Passover means bringing the family together, and for that reason it was his favorite holiday as a kid. There’s just something very moving about an idea like this at a time like this.